It’s May 14, so she posts a birthday photo on Instagram: a selfie in scrubs after a long hospital shift, or maybe a studio portrait with balloons and a caption: “Grateful for 22.”

In the portrait, her hair is curled softly around her face, her gentle smile lighting up the frame. Friends flood the comments section with heart emojis and warm wishes.

At home, her mum bakes her favourite cake in white and black; her favourite colours. Her dad says a quiet prayer, blessing her for the year ahead. Her younger brother teases her over the phone, calling her “old” and laughing together like always.

This version of today exists only in imagination. There’s no photo. No candles. No celebration.

Leah Sharibu is still in captivity. She turns 22 today.

“She wanted to be a doctor,” her younger and only sibling, Donald Sharibu, tells HumAngle. “It wasn’t just about studying medicine. She liked helping people. She always offered to assist someone with chores, homework, anything.”

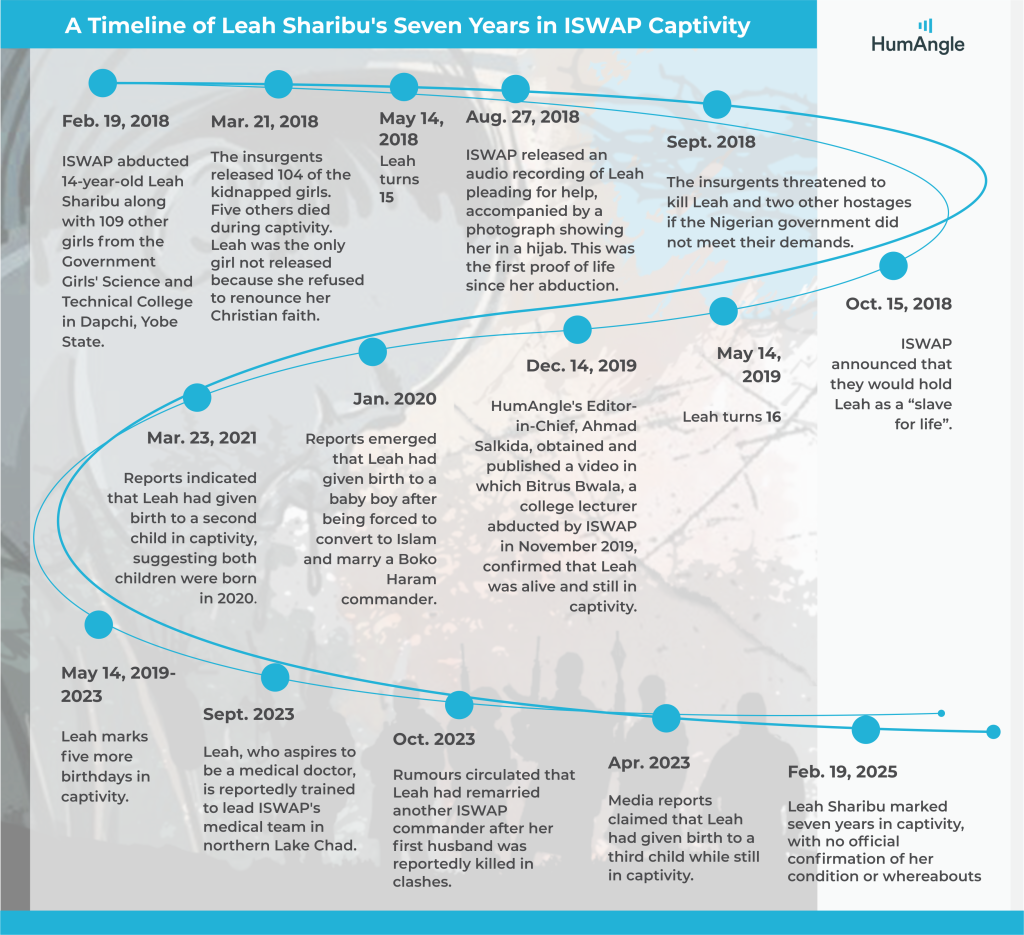

Leah was just 14, three months shy of her 15th birthday, when the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), a Boko Haram breakaway, stormed her school, Government Girls’ Science and Technical College in Dapchi, Yobe State, northeastern Nigeria. It was on Monday evening, Feb. 19, 2018, and they raided the dormitories, herding terrified students into waiting trucks. One hundred and ten schoolgirls, including Leah, were abducted.

Five died along the way.

By March 21, 2018, 104 had been released. But Leah was left behind.

Donald, now 20, still remembers when the rumours about the attack in Dapchi began; he was in a boarding school in Nguru, several kilometres from home.

“Like me, most of my roommates were from Dapchi. At first, I thought the attack was somewhere in the town. I didn’t know it was my sister’s school,” Donald recounts.

He borrowed a phone and called home. Their mother, a teacher, picked up. “She said Leah’s school had been attacked,” he says. “I brushed it off. I didn’t think she was involved. She’s smart, careful. I thought maybe she escaped and would come back.”

The next day, his mother called. She was sobbing. Leah had been abducted.

Donald was still convinced that his sister would escape, and indeed, she attempted to flee while in captivity. Fatima Mohammed, one of the released Dapchi schoolgirls, told HumAngle that she was caught, and then the insurgents realised she was a Christian.

Fatima said Leah was asked to convert to Islam or remain their captive. “We begged her to pretend to convert, but she refused,” she recounted.

As time trudged forward with no word, Donald’s hope for his sister’s escape slowly faded. The family, unable to bear the weight of their grief in Dapchi, eventually relocated to Yola, the Adamawa State capital, seeking some semblance of peace far from the memories that haunted them.

“My mother resigned from teaching at a school in Dapchi, and then we left,” he says.

Donald also left Nguru. His parents transferred him to ECWA Staff School in Jos, Plateau State, North-central Nigeria, where he completed his secondary education.

Originally from Hong, a local government area in Adamawa State, the Sharibus are a devout Christian family; they attend Evangelical Church Winning All, commonly known as ECWA, one of the largest Christian denominations in northern Nigeria. Their faith runs deep, not performative but lived in prayer, community, and Leah’s quiet resolve.

Donald had just returned from a Sunday service when he joined a WhatsApp call with HumAngle. Like his sister, he is deeply rooted in his faith. He is the president of the Christian fellowship on campus, holding on to his belief, even when answers remain out of reach.

Seven years on, Donald is going into his final year at the American University of Nigeria in Yola, studying International and Comparative Politics, a future his sister was meant to experience first, as the family’s first-generation graduate.

She was in SS2, just one academic year from finishing secondary school, when she was abducted. By now, she should have been in her final year at the university, perhaps doing clinical rounds in a hospital. Even if admission hurdles in Nigeria had forced a change in course, and she didn’t read medicine, Leah might have graduated, completed her NYSC year, with an enlarged picture of her in khaki uniform sitting on the wall in their parents’ living room with quiet pride, and even secured her first job.

“She would have been doing something by now,” Donald says. “Leah is hardworking.”

Many of the released Dapchi schoolgirls dropped out of school after their return and married. Aisha Mahmuda, one of the girls who also led the failed escape plan Leah was part of, said she and her mother decided that returning to school was not worth the risk. “So we agreed that I would just get married,” Aisha told HumAngle.

But Donald believes it would have been different for his sister. “Our dad didn’t go beyond secondary school, but always said that education is everything. He pushed us to reach further,” he says.

No day goes by without Donald thinking about Leah. They were very close; they attended the same schools until he left for senior secondary school in Nguru. She was the older sister who helped with homework and shared inside jokes. “She is kind and jovial,” he recounts.

He imagines her sometimes. Calling, having conversations, sharing stories, praying, and everything else.

“I really look forward to such a day,” he says.

For now, though, there are no new photographs, no voice notes, or video calls. Just fleeting rumours and unverified reports: whispers of a forced marriage to at least two insurgents, of children born in captivity, of a girl becoming a woman under a regime of coercion, isolation, and silence.

“It is hurtful, no one, no family should go through this,” Donald says. “She used to talk about marriage. But not like this. Not at this age.”

Some of the Dapchi girls who were released told HumAngle that while they were in captivity, they would sometimes have conversations with the wives of the insurgents. Many of them “told us that they became their wives after they were abducted in the same manner that we were.”

Multiple sources confirmed to HumAngle that Leah is being held in the Bosso region of the Republic of Niger, a rural community along Nigeria’s northern border.

According to Philip Dimka, a clinical psychologist and trauma therapist who works with conflict-affected individuals in North-central Nigeria, spending seven years in captivity can profoundly affect a young person’s mental health, development, and identity. “At that age, captivity is deeply damaging,” he says. “It’s a crucial stage of growth. Being forced into a new environment can trigger isolation, confusion, and an identity crisis. Prolonged stress, especially with abuse, can lead to complex trauma or PTSD. The brain is still developing, and constant fear can disrupt that process.”

One possible consequence, he notes, is Stockholm syndrome, where captives form emotional bonds with their captors. “It’s not about love or loyalty,” he explains. “It’s about fear and powerlessness. The mind, often subconsciously, finds ways to adapt and create a sense of stability.” Still, not everyone develops such bonds. Reintegration can be jarring, especially when families or society expect a return to ‘normal’. Without proper psychological support, trauma may surface as anxiety, depression, or a fractured sense of self. “Healing is possible,” Philip added.

The Nigerian government has repeatedly promised to secure Leah’s release, but the promises have rung hollow. Advocacy groups and faith-based organisations have also called attention to her case, but as the years pass, global headlines shift and the urgency fades from the conversation.

“Our government doesn’t prioritise the safety of its people. We need to treat symptoms of armed violence early, it becomes difficult when we allow it to grow,” says Donald.

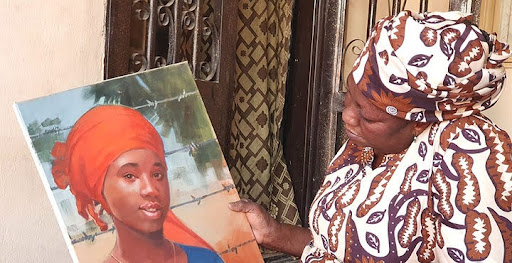

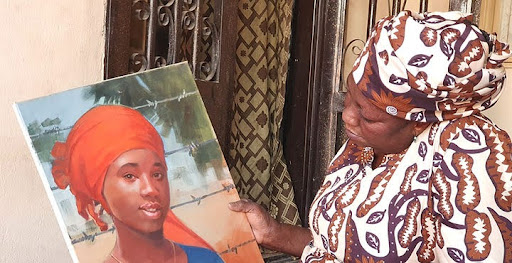

Still, for the Sharibus, every day is a waiting day; they’ve not heard from her since her abduction. Every phone call brings hope, every rumour a spark, and then, often, disappointment.

For her family, Leah’s 22nd birthday will be marked in quiet prayer, far from where she should be. Her mum fainted when she first heard about the abduction. It weighed so much on them, but Donald says his parents are doing much better now.

“We are hopeful that she will return,” he says. “We’re not giving up.”

“We pray for her as a family every day,” Donald tells HumAngle.

The Sharibus are not the only ones praying. At noon on her birthday this year, dozens of well-wishers will gather on Zoom to intercede for her release. The event is organised by the Leah Foundation, a non-profit founded in May 2018 by a coalition of Christian leaders, in partnership with her parents, after the world learned that she was still in captivity because she refused to renounce her faith.

“We believe God responds to united prayer. Seven is a number of completion, and we ask God to release Leah from her 7-year captivity,” the organisation said in a statement.