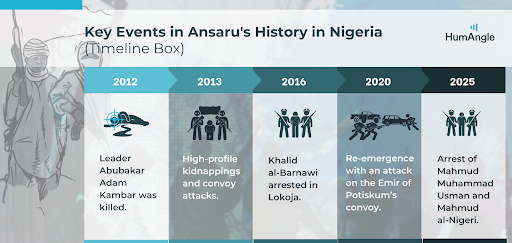

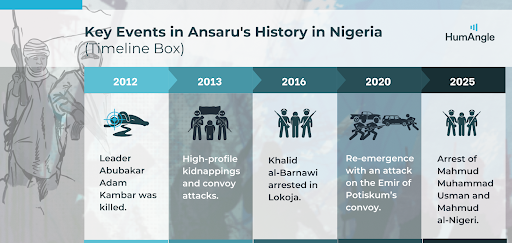

On Aug. 16, Nigeria’s National Security Adviser (NSA), Nuhu Ribadu, announced that security services had captured two terror leaders, including Mahmud Muhammad Usman, described as a leader of the al-Qaida-linked faction Jama’atu Ansarul Muslimina fi Biladis Sudan, popularly known as Ansaru. Authorities also said they had detained Mahmud al-Nigeri, who is associated with the emergent Mahmuda network in North Central Nigeria.

The arrests, made during operations that spanned May to July this year, were described by the NSA as “the most decisive blow against Ansaru” since its inception, with officials hinting that digital material seized could unlock additional cells and enable follow-on arrests.

“These two men have jointly spearheaded multiple attacks on civilians, security forces and critical national infrastructure. They are currently in custody and will face due legal process,” Ribadu noted.

For a government under pressure to tame overlapping threats from terrorists, this is a political and operational win. The harder question is whether it marks an actual turning point in a fragmented conflict that has repeatedly adapted to leadership losses.

A short history of a long problem

Ansaru emerged publicly in early 2012 as a breakaway from Boko Haram after years of quiet cross-border travel, training, and ideological cross-pollination with al-Qaida affiliates.

The split reflected disagreements over targeting and ideological tactics. While Boko Haram, under Abubakar Shekau, embraced mass-casualty violence, including suicide attacks that killed several civilians, including Muslims, Ansaru positioned itself as a more “discriminating” outfit, focused on Western and high-profile Nigerian targets and on hostage-taking for leverage.

The group’s founders, notably Khalid al-Barnawi and Abubakar Adam Kambar, had networks developed through al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which shaped their doctrine and operational tactics. This lineage remains crucial for understanding Ansaru’s strategic choices and its enduring connections in the Sahel.

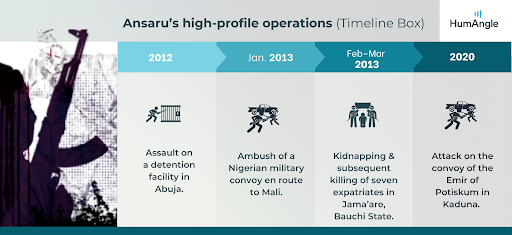

Ansaru’s first phase was brief but consequential. Between late 2012 and early 2013, the group was credibly linked to a string of operations: the storming of a detention site in Abuja, the country’s capital city, on November 2012, the attack on a Nigerian convoy bound for Mali in January 2013, and, most notoriously, the 2013 kidnapping of seven expatriate workers from a Setraco construction camp in Jama’are, Bauchi State in the country’s North East. The hostages were later killed, and Ansaru circulated a proof-of-death video that stunned Nigeria’s security community.

Those incidents cemented the group’s image as an al-Qaida-influenced kidnap-and-assault specialist rather than a proto-governance insurgency.

Two leadership shocks then disrupted Ansaru’s momentum. In 2012, Abubakar Adam Kambar, the group’s first commander, was reported killed during a security operation, elevating Khalid Barnawi’s importance inside the network.

In April 2016, security forces arrested Khalid al-Barnawi in Lokoja, Kogi State, in the North Central, an event that was widely seen as decapitating Ansaru’s remaining central structure. Ansaru then disappeared from public claim streams for several years after that arrest, an action that suggested the group’s command and control was genuinely degraded.

However, in January 2020, Ansaru reappeared with an ambush on the convoy of the Emir of Potiskum as it transited through Kaduna State in the North West. Later that year, it issued additional claims in the same region, signalling a pivot from its northeastern birthplace toward spaces where state presence was thinner and terror violence had created both a security vacuum and a recruitment market.

Reports, including one published by HumAngle, traced some of this revival to the group’s continued ties with al-Qaida affiliates in the Sahel and pragmatic cohabitation with terror gangs, whether through facilitation, training, or weapons flows.

Why the recent arrests matter

The recent arrests resemble earlier moments when big names like Abubakar Adam Kambar were taken off the battlefield. Officials say Mahmud Muhammad Usman and his counterpart from the Mahmuda network were not only operational leaders but also brokers of transnational connections, including alleged roles in orchestrating the 2022 Kuje prison break and in a 2013 attack against a Nigerien uranium site.

“Malam Mamuda, was said to have trained in Libya between 2013 and 2015 under foreign jihadist instructors from Egypt, Tunisia, and Algeria, specialising in weapons handling and Improvised Explosive Device (IED) fabrication,” Ribadu said

Those claims serve a dual purpose. They frame the detentions as part of a campaign that reaches beyond Nigeria’s borders, and they signal to international partners that Abuja is aligning against a regional terrorist web that spans from Northern Nigeria through Niger and into Mali and Burkina Faso.

The tactical benefits are clearer. Removing senior fixers disrupts the flow of money, weapons, and specialised expertise that enable small cadres to punch above their numerical weight.

The haul of digital media, if exploited quickly, can reveal safe-route maps, dead-drop protocols, and liaisons inside other terror syndicates that lease out men and terrain in north-west and north-central Nigeria. When combined with focused policing in towns and market hubs, that intelligence can shrink Ansaru’s margins for clandestine movement and fundraising.

None of this ends the threat on its own, but it changes the tempo and increases the cost to operate.

What is Ansaru, and what is it not?

To understand fully what this moment means, it is useful to situate Ansaru among the three principal jihadist currents that affect Nigeria today: Boko Haram’s Jama’atu Ahlis-Sunna lid-Da‘wa wal-Jihad (often called “JAS” or “Shekau’s faction”), the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), and Ansaru itself.

JAS was, for years, the most visible face of the insurgency, built around an absolutist and takfiri reading of Salafi-Jihadism, and operationalised through terror attacks that did not distinguish Muslim civilians from security targets. The Shekau era normalised female suicide bombers, mass abductions, and village-level depopulation. Governance was secondary to spectacle and intimidation. Since Shekau died in 2021, JAS has splintered and receded in some arenas, although pockets remain capable of lethal violence.

ISWAP is different. Born of a schism with Shekau, it has tended to emphasise territorial management in the Lake Chad Basin, with taxation, shadow court systems, and calibrated violence designed, at least nominally, to avoid indiscriminate Muslim casualties. Its commanders often court pragmatic relationships with traders and smugglers, and, unlike JAS in its prime, ISWAP markets itself as predictable enough for civilians to bargain with and understand. International Crisis Group and other researchers have long highlighted these governance motifs as operational advantages, even as ISWAP continues to attack military positions and abduct civilians.

Ansaru occupies a third lane. Its al-Qaida genealogy predisposes it toward targeted kidnappings of foreigners and high-profile Nigerians, ambushes of convoys, and the cultivation of rural social capital.

During its 2020 and 2022 push in the North West, Ansaru proselytisers distributed food and farm inputs, positioned themselves as protectors against predatory terrorists, and sought to embed preachers who preached against secular politics and democratic participation. This hearts-and-minds approach was less about running a taxation state and more about building safe communities of sympathy to hide in, recruit from, and extract logistics support.

Ideologically, Ansaru’s guides are AQIM and, by extension, JNIM in the Sahel. That lineage favours calibrated violence, prolonged detentions rather than mass executions, and strategic hostage bargaining, as seen in the Setraco case and other high-profile kidnappings from 2012 to 2013. It also means Ansaru is plugged into the Sahelian marketplace for weapons, trainers, and media distribution, which helps explain its periodic ability to rebound after leadership losses.

A map of influence, not of control

In the North East, ISWAP and residual JAS cells dominate the insurgent landscape. Ansaru’s post-2019 story unfolded more in Kaduna’s rural west and parts of neighbouring states, where the absence of policing and the rise of kidnap-for-ransom gangs created both a protection racket and an opportunity for ideological entrepreneurs.

Birnin Gwari Local Government Area in Kaduna State became a shorthand for that nexus. Residents and local leaders reported that Ansaru courted communities, fought some local terrorist groups, and tried to regulate flows on key feeder roads.

Media and civil society reports described the group distributing Sallah gifts in Kuyello and influencing daily life in and around Damari and other settlements. These were snapshots of temporary influence, not evidence of continuous territorial control, but they were a warning sign that non-state governance was thickening in spaces where the state was thin.

That is the context in which Ribadu’s announcement landed. If the commanders arrested were connective tissue between al-Qaida-adjacent logisticians, local fixers, and local terrorist entrepreneurs, then removing them will reverberate in Birnin Gwari and similar corridors. It is also why the arrests were paired rhetorically with claims about plots and partnerships far from Kaduna, including across the Maghreb and the Sahel.

The Federal Government wants Nigerians to see Ansaru not as another rural gang, but as a node in a continental web that justifies sustained, internationally backed counterterrorism.

Lessons from 2012 and 2016

This is not Nigeria’s first experience with decapitation strikes against Ansaru. In 2012, the reported killing of Kambar set off internal adjustments.

In 2016, the arrest of Khalid al-Barnawi appeared to shutter Ansaru’s media pipeline and disrupt its external ties, which supports the argument that leadership matters for a relatively small, networked faction.

Yet by 2020, the group was reclaiming relevance in the northwest, an adaptation that coincided with the Sahel’s worsening jihadist crisis and the metastasis of rural banditry inside Nigeria.

This short history suggests a dual lesson: Taking leaders off the board works, especially when accompanied by seizures of communications and couriers. However, it works less well when ungoverned spaces expand faster than the state can fill them and when adjacent theatres, like Mali and Burkina Faso, are producing more seasoned cadres than the region can absorb.

History suggests that leadership arrests slow Ansaru down, but do not end its threat. The group has survived by blending into rural bandit-terrorist networks and leveraging its ties to al-Qaida affiliates in the Sahel.

Operations that shaped Ansaru

Ansaru’s brand was shaped by a handful of headline incidents:

Kidnapping and killing of foreign construction workers, Jama’are, Bauchi State, February–March 2013. Seven expatriates seized from Setraco’s compound were later executed after a period of captivity. The case demonstrated Ansaru’s preference for hostage taking aimed at political signalling and bargaining leverage, even if the outcome was ultimately murderous.

Attack on Nigerian troops en route to Mali, Kogi State, January 2013. As Abuja prepared to contribute forces to the international intervention against jihadists in northern Mali, Ansaru claimed a lethal ambush that underlined its Sahel-centric framing and its willingness to hit military targets to deter Nigeria’s regional role.

A cluster of 2012 operations, including an assault on a detention facility in Abuja and kidnappings such as the abduction of a French national. The pattern resembled AQIM’s repertoire in the Sahel more than Boko Haram’s campaign in Borno, with a focus on foreigners, convoys, and facilities that maximised international attention.

More recently, investigators and journalists have traced Ansaru’s fingerprints to influence activities in Kaduna’s rural belt, including the deployment of preachers, gift distribution to farmers, and cooperation or competition with bandit factions. Even where attribution is contested, the persistence of these reports speaks to Ansaru’s hybrid strategy of armed proselytisation and transactional coexistence.

What the arrests change, and what they do not

The most optimistic reading is that neutralising senior Ansaru leaders will slow operational planning, complicate cross-border procurement of arms, and deter terrorist groups from entering into further tactical pacts. In the near term, that could translate into fewer complex ambushes, fewer kidnappings with political messaging, and a reduction in the movement of specialist bombmakers or media operatives between northwest Nigeria and Sahelian fronts.

If the digital evidence that Ribadu referenced is robust and rapidly exploited, the state could also roll up facilitators in markets, transport unions, and phone shops that act as the quiet arteries of clandestine groups.

A more cautious reading is grounded in Ansaru’s history and the adaptive ecology of violence in the North West. The group is small, but it has repeatedly used alliances to magnify its reach. If surviving mid-level cadres can maintain relationships with bandit-terror leaders who control forest sanctuaries and rural taxation points, Ansaru can regenerate a functional structure even without marquee names at the top.

In some cases, the brand itself is a currency: men can claim to be acting on behalf of Ansaru to secure access, while the real command node sits far away and communicates sparingly. Detentions alone do not break that reputational economy.

There is also the question of displacement. Pressure in one theatre can push cadres into neighbouring spaces. As long as Sahelian conflict systems continue to produce itinerant trainers and brokers with AQIM or JNIM pedigrees, there will be a supply to meet Nigeria’s demand for clandestine services. Here, the government’s signalling about cross-border links is more than public relations. It points toward the necessity of intelligence sharing with Niger, and, depending on the political climate, with authorities in Mali and Burkina Faso, where applicable. Securing those partnerships in an era of coups and shifting alliances is not a technical task. It is political.

What would “success” look like six months from now?

A realistic definition of success is not zero attacks, but measurable attrition in Ansaru’s facilitation capacity and a visible shrinking of its rural social space. There are indicators Nigerians can watch for:

- Fewer kidnap incidents with clear ideological framing in Kaduna’s rural west and adjacent corridors, and more arrests of kidnap coordinators with al-Qaida ties.

- Disruption of preacher networks that have been used to socialise communities into Ansaru’s worldview, ideally with community-led alternatives filling the vacuum.

- Intelligence-led seizures on trunk and feeder roads that connect markets in Kaduna and Niger States to forest hideouts, particularly around Birnin Gwari, Kuyello, and Damari.

- Public defections of mid-level facilitators following a perception that the brand can no longer protect them from arrest or rival bandits.

If kidnappings bridge into the harvest season with familiar signatures, or if new names suddenly surface to replace those detained, then the state will need to ask whether it has struck the right balance between kinetic pressure and political management of the rural economy of violence.

The bottom line

Ribadu’s announcement is welcome news in a war that has lacked good headlines. For a government facing simultaneous pressure in the North East and the North West, removing Ansaru leaders offers a chance to disrupt one of the more insidious cross-border pipelines feeding violence in Nigeria’s heartland.

The history, though, counsels humility. Ansaru has absorbed leadership losses before, gone quiet, and then reconstituted itself where the state was weakest. What comes next will depend less on what was said at a podium than on what happens on back roads and in forest clearings, at checkpoints and market stalls, and in the daily bargains between frightened communities and the armed men who claim to protect or prey on them.

If the new arrests are leveraged to dismantle facilitation networks, to keep pressure on safe havens, and to fill the governance gap that Ansaru has so skillfully exploited, then Nigeria could indeed be at a turning point. If not, the country risks watching this chapter follow the pattern of 2012 and 2016, when a decapitated network lay low and then returned in a new guise.

The choice now is whether to treat this as a headline or as the start of a sustained campaign that finally closes Ansaru’s page in Nigeria’s long insurgent story.