MEXICO CITY — In a packed nightclub in Mexico City, hundreds of young people sang along as a band played a popular song narrating the life of a foot soldier for the Sinaloa drug cartel.

I like to work/ And if the order is to kill / You don’t question it.

And for those who misbehave/ There’s no chance to explain/ I throw them into the grave.

Narcocorridos — or drug ballads — are more popular than ever in Mexico, where a new generation that came of age during the ongoing drug war has embraced songs that recount and often glamorize both the spoils and perils of organized crime.

But the genre is increasingly under attack. About a third of Mexico’s states and many of its cities have enacted some kind of ban on the performance of songs about narcos in recent years, with violators subject to heavy fines and jail time.

Mexico City may be next. Mayor Clara Brugada said she plans to introduce a law that would bar the songs from being played at government events and on government property.

“We can’t be promoting violence through music,” she said.

Musicians perform at the popular Los Guitarrazos event in Mexico City, where narcocorridos, or drug ballads, are common.

The bans, which come amid President Trump’s hyper-focus on drug trafficking in Mexico, have sparked debates here about freedom of expression and state censorship and have raised provocative questions: Do narcocorridos merely reflect reality in a nation gripped by powerful drug gangs? Or do they somehow shape it?

Said Amaya, the organizer of Guitarrazos, the event at the nightclub in Mexico City where multiple singers performed narcocorridos last week, said government focus should be on improving security, not persecuting young musicians.

“If you change the reality, the music might change,” Amaya said. “But you’re not going to change the reality by censoring songs.”

Drug ballads belong to the genre of corridos, a musical tradition born in the 1800s that helped chronicle life at a time when many people couldn’t read or write.

Each song told a story. There were corridos about the exploits of bandits and outlaws, some of them Robin Hood-esque characters who outwitted oafish authorities and helped the poor. Others narrated chapters of the Mexican Revolution or the U.S. invasion of Mexico in 1846.

In more recent years, as Mexico became a key gateway for the U.S. drug market, enriching some people and claiming the lives of hundreds of thousands of others, musicians have described that, too.

“The entire social history of Mexico is narrated through corridos,” said José Manuel Valenzuela Arce, a sociologist in Tijuana. “It’s an intangible part of our cultural heritage.”

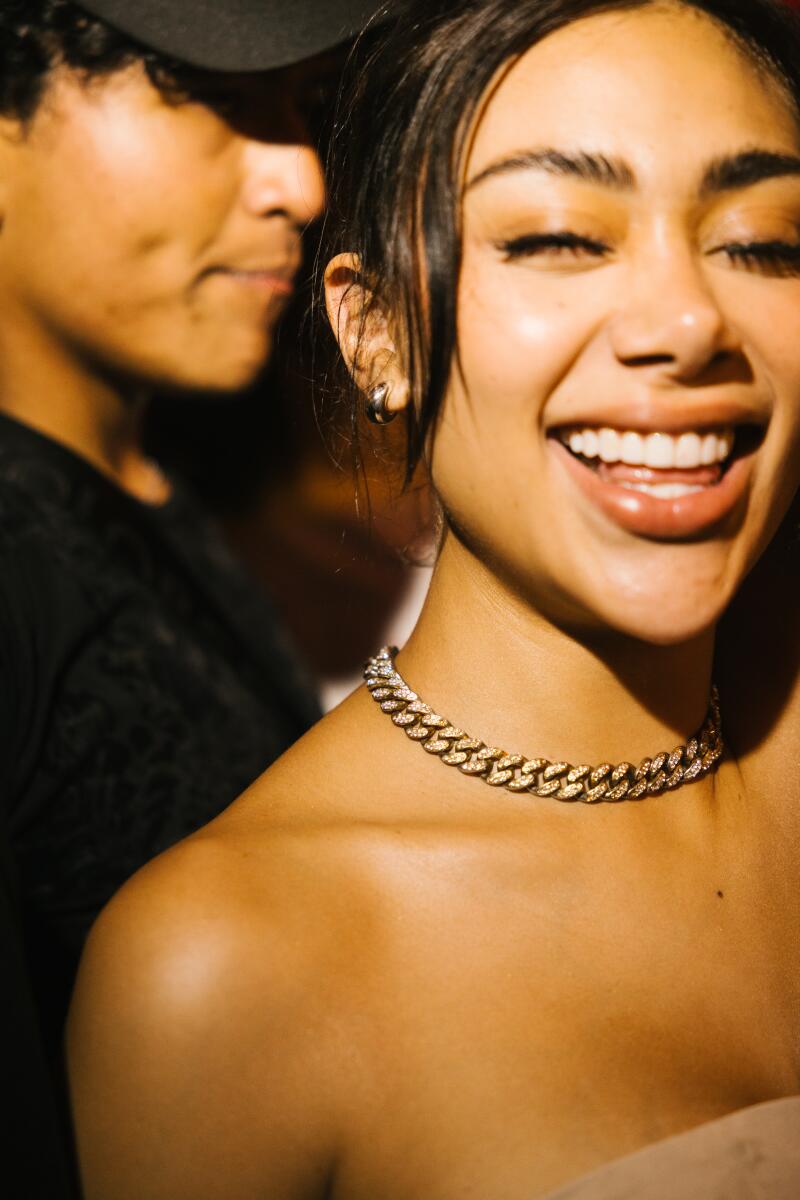

1. An audience member wears a diamond chain on the dance floor at Los Guitarrazos. 2. Drug ballads belong to the genre of corridos, a musical tradition born in the 1800s that helped chronicle life at a time when many people couldn’t read or write.

Valenzuela wrote a book about the newest version of drug ballads, known as corridos tumbados, which combine acoustic guitar, brassy horns and the aesthetic and lyrical content of U.S. gangster rap. Proponents of the music, like artist Peso Pluma, who performs in ballistic vests and sings of diamond-encrusted pistols and shipments of cocaine, have brought the genre to global audiences.

The 25-year-old musician, whose name translates to “Featherweight,” was the seventh most streamed artist in the world on Spotify last year. In 2023, former President Obama included in his top 10 songs of the year a Peso Pluma song that does not touch on drug trafficking.

Musicians dedicated to the genre have long faced backlash from the government, which since the 1980s has tried, at various times, to ban the music.

But the long-standing controversy exploded back into public life this year after a concert in Michoacan state by the band Los Alegres del Barranco, which displayed images of Nemesio Rubén Oseguera Cervantes, better known as El Mencho, who heads the Jalisco New Generation Cartel. The band played at a venue not far from a gruesome cartel training camp that authorities had just discovered.

The concert outraged many Mexicans, and Michoacan Gov. Alfredo Ramírez Bedolla soon announced a ban on public performances that glorify crime and violence. That was followed by similar measures in other states, including Aguascalientes, Queretaro and Mexico state.

A performer plays his guitar with a beer bottle at Los Guitarrazos, a Mexico City event featuring artists playing the northern Mexican genre corridos.

Days later, the Trump administration announced it was revoking the U.S. visas of the members of Los Alegres del Barranco.

“The last thing we need is a welcome mat for people who extol criminals and terrorists,” Deputy Secretary of State Chris Landau said on X.

President Claudia Sheinbaum says she does not support the bans, but also doesn’t support the music. She recently announced a national song competition for compositions about subjects other than drug trafficking.

“More than banning, it’s about educating, guiding, and getting young people to stop listening to that music,” she said.

But the bans have momentum — a recent poll found that 62% of those surveyed support prohibitions on narcocorridos — and they have put the genre’s stars in a tricky position. Their fans demand they play their hits, but doing so is increasingly risky.

Performing in one of the states that had banned the songs last month, artist Luis R. Conríquez refused to play his ballads that romanticize drug traffickers.

Audience members were enraged, forcing him off stage as they flung insults, beer bottles and chairs, and later destroyed his band’s instruments.

A singer performs at Los Guitarrazos, an event featuring artists playing the northern Mexican genre corridos, on Tuesday, May 6, 2025 in Mexico City, Mexico.

Others musicians, such as corridos tumbados star Natanael Cano, have pressed on despite the bans.

The 24-year-old performed at an annual fair in Aguascalientes state this month just days after the local authorities warned musicians not to play narco songs.

He began his set with songs from his repertoire that touch on love and other subjects. But soon fans were pleading for popular songs such as “Cuerno azulado,” which talks about blue-tinted AK-47s and pacts between drug traffickers and the government.

Cano first told audience members they should press their leaders to roll back the bans.

“You have to ask your government,” Cano said. “Don’t come here asking me for it.”

Audience members at a club in Mexico City where musicians performed narcocorridos, a genre many states are trying to outlaw.

But eventually he acquiesced, playing a song called “Pacas de Billete,” or “stacks of cash,” which alludes to “El Chapo,” the Sinaloa drug cartel kingpin Joaquín Guzmán. After the event’s organizers cut the sound, Cano’s team activated their own audio system. Eventually, though, the lights were turned out and the artist left the stage and headed directly to the airport. Local authorities have not pressed charges against him.

A few years ago, Cano was slapped with a $50,000 fine for performing narcocorridos in Chihuahua, one of the first states to enact a ban.

Los Alegres del Barranco, the band that flashed a picture of El Mencho in Michoacan, has tried to skirt the laws in recent days with karaoke events in which they play the music but project lyrics for the audience to sing.

For many stars, the bigger threat may be organized crime itself. Drug traffickers often pay to be featured in songs — Peso Pluma has acknowledged taking money from them — and dozens of the genre’s stars have been killed over the years, sometimes by rivals of the hit men and drug dealers they’ve portrayed. Peso Pluma canceled an appearance in Tijuana last year after he received death threats.

Those who support the bans say they are necessary to keep the next generation of young people from romanticizing violence, and to honor those who have lost loved ones to bloodshed.

“Will we tell the victims and their families that it is better to respect the freedom of expression of those who advocate violence than to take measures to safeguard the lives of Mexicans?” columnist Mauricio Farah Gebara wrote in Milenio newspaper.

But for the genre’s devotees, the bans smack of classism.

A musician plays the double bass.

1. An audience member records the musicians play. 2. An audience member wears a diamond chain bracelet.

It’s a double standard, said a musician named Rosul, who often performs narcocorridos and who attended the lively party in Mexico City last week.

“Netflix can release a series about drug traffickers and win awards and get applause,” she said. “But if somebody from the ‘hood sings about the same thing, it’s an apology for violence?”

Banning the genre, she said, is a losing battle. Young people, after all, hate being told what to do.

“This only makes it more appealing,” she said. “This will only make us stronger.”

Times special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez Vidal contributed to this report.