We live in a world where racism isn’t just a set of isolated incidents but a pervasive thread woven through every major system and institution that shapes our daily lives. The evidence surrounds us, yet many “fail to see it.” The roots of racism are deeply ingrained into the fabric of society. For example, something as simple as redlining, where financial institutions deny loans for specific neighborhoods based on race, is one such tool of racism. The systems around African-Americans were not designed to uplift but rather to suppress their existence. To demand equality, justice, and human rights, we must confront the inequalities embedded within our economic, legal, educational, healthcare, and political systems and work to deconstruct the structures that have long marginalized Black communities.

One of the most glaring manifestations of systemic racism is the racial wealth gap between African-Americans and white Americans. According to a recent article published by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), the median wealth of Black households is just $9,000, compared to $160,200 for white households. This vast disparity is not simply the result of individual choices or personal shortcomings but stems from centuries of exclusionary economic policies like slavery, Jim Crow laws, and discriminatory housing practices like redlining. As a result, African-American families have been systematically denied opportunities to build wealth through homeownership, business ownership, and access to financial resources.

Educational inequality is another major facet of systemic racism that has profound long-term effects on the African-American community. Despite the progress made in desegregating schools, the reality is that African-American children are still more likely to attend underfunded schools. According to a study done by EdBuild, schools that are predominantly white school districts receive $23 billion more than those in districts where the students are not predominantly white. This means fewer resources, less support, and a lower quality education, creating a cycle of limited educational achievement that would hinder economic mobility. School funding is often tied to local property taxes; according to the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, 81% of school funding comes from property taxes. This means that communities with lower-income populations—disproportionately populated by Black families— have far fewer resources than affluent, predominantly white districts. The lack of access to quality education and the disproportionate funding faced by Black students has long-term consequences for their future success, limiting access to higher education and career opportunities.

The racial inequities in the healthcare system are stark and continue to aggravate the health disparities experienced by African-Americans. African-Americans are also more likely to suffer from chronic conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and asthma, yet are less likely to receive appropriate care for these conditions. The higher rates of poor health outcomes for African-Americans are attributed to multiple factors, including lack of access to quality healthcare, economic barriers, and institutional biases within the medical field. Additionally, African-American women are three times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes compared to their white counterparts. This crisis is driven by factors such as implicit bias in healthcare, where doctors may underestimate the pain of Black patients or fail to treat them with the same urgency as white patients. Despite improvements in healthcare access over the past several decades, these racial disparities persist and continue to contribute to poor health outcomes faced by African-Americans.

Despite growing support for addressing systemic racism, some argue that institutional inequalities are a thing of the past and that modern society offers equal opportunities to all. People against structural change often claim that disparities in wealth, education, and incarceration rates are due to individual choices rather than systemic barriers. They point to examples of successful Black Americans—CEOs, politicians, and entertainers—as evidence that racism is no longer a defining factor in American society. Some even argue that programs aimed specifically at correcting racial inequalities are themselves discriminatory, advocating instead for “colorblind” policies that treat all individuals the same. But this argument crumbles under the weight of historical context and current data. The presence of a few high-profile Black success stories does not erase centuries of legally sanctioned oppression or the enduring structures that continue to disadvantage millions of Black Americans. Relying on exceptionalism to dismiss systemic issues is dishonest—it ignores the reality that for every one Black millionaire, there are countless others facing discrimination in housing, education, employment, and healthcare. “Colorblindness” sounds appealing in theory, but in practice, it erases the unique challenges that the African-American community faces, making it harder, not easier, to achieve real equity.

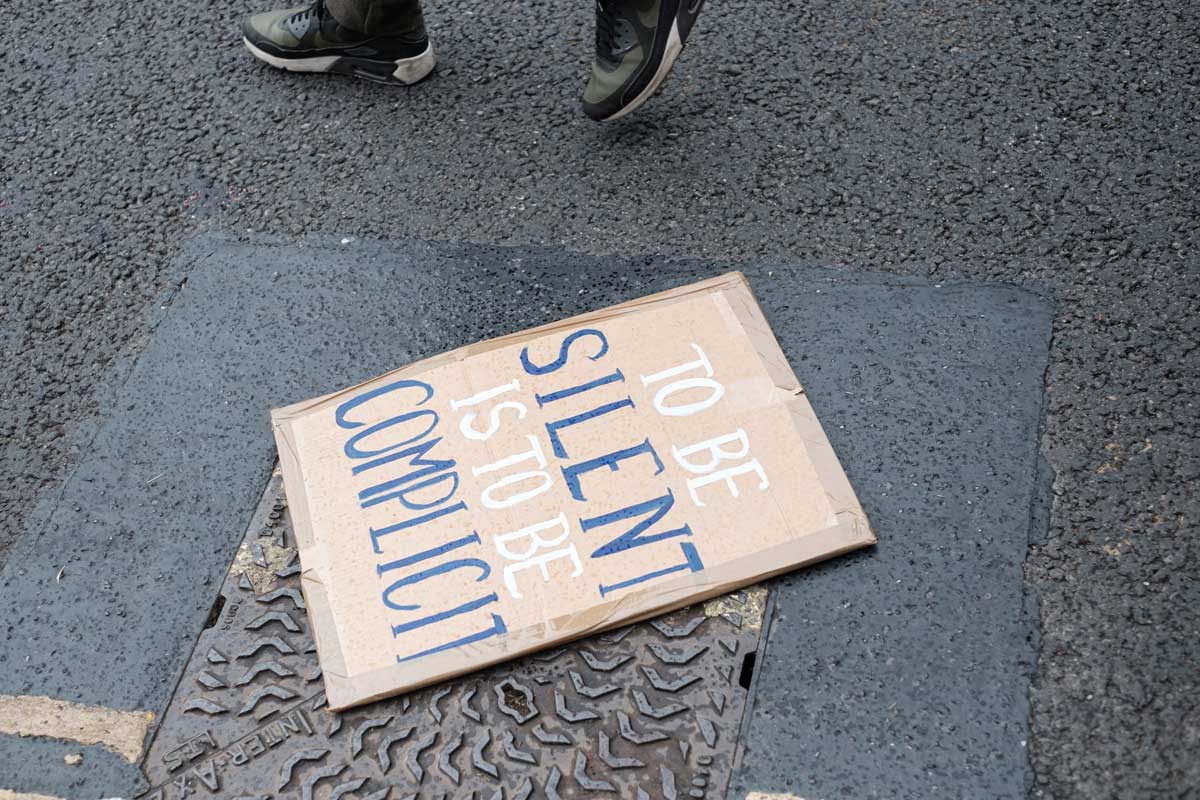

Deconstructing institutionalized racism is not just a political task—it is a moral imperative. For centuries, African Americans have carried the weight of a system built to exclude them while being told to be patient, to work harder, and to wait for justice that never fully arrives. The pain is generational. The harm is measurable. And the silence of inaction is deafening. We cannot repair what we refuse to acknowledge. True justice requires us not to ignore race but to confront how it has been weaponized for generations. To suggest otherwise is not only naive—it’s dangerous. It’s time to rebuild a society that doesn’t just promise equality but delivers it.