BBC News, Mumbai

Getty Images

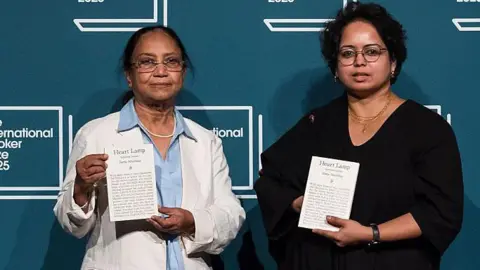

Getty ImagesIndian writer-lawyer-activist Banu Mushtaq has scripted history by winning the International Booker prize for the short story anthology, Heart Lamp.

It is the first book written in the Kannada language, which is spoken in the southern Indian state of Karnataka, to win the prestigious prize.

The stories in Heart Lamp were translated into English by Deepa Bhasthi.

Featuring 12 short stories written by Mushtaq over three decades from 1990 to 2023, Heart Lamp poignantly captures the hardships of Muslim women living in southern India.

In her acceptance speech, Mushtaq thanked readers for letting her words wander into their hearts.

“This book was born from the belief that no story is ever small; that in the tapestry of human experience, every thread holds the weight of the whole,” she said.

“In a world that often tries to divide us, literature remains one of the last sacred spaces where we can live inside each other’s minds, if only for a few pages,” she added.

Bhasthi, who became the first Indian translator to win an International Booker, said that she hoped that the win would encourage more translations from and into Kannada and other South Asian languages.

Mushtaq’s win comes off the back of Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand – translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell – winning the prize in 2022.

Her body of work is well-known among book lovers, but the Booker International win has shone a bigger spotlight on her life and literary oeuvre, which mirrors many of the challenges the women in her stories face, brought on by religious conservatism and a deeply patriarchal society.

It is this self-awareness that has, perhaps, helped Mushtaq craft some of the most nuanced characters and plotlines.

“In a literary culture that rewards spectacle, Heart Lamp insists on the value of attention – to lives lived at the edges, to unnoticed choices, to the strength it takes simply to persist. That is Banu Mushtaq’s quiet power,” a review in the Indian Express newspaper says about the book.

Who is Banu Mushtaq?

Mushtaq grew up in a small town in the southern state of Karnataka in a Muslim neighbourhood and like most girls around her, studied the Quran in the Urdu language at school.

But her father, a government employee, wanted more for her and at the age of eight, enrolled her in a convent school where the medium of instruction was the state’s official language – Kannada.

Mushtaq worked hard to become fluent in Kannada, but this alien tongue would become the language she chose for her literary expression.

She began writing while still in school and chose to go to college even as her peers were getting married and raising children.

It would take several years before Mushtaq was published and it happened during a particularly challenging phase in her life.

Her short story appeared in a local magazine a year after she had married a man of her choosing at the age of 26, but her early marital years were also marked by conflict and strife – something she openly spoke of, in several interviews.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn an interview with Vogue magazine, she said, “I had always wanted to write but had nothing to write (about) because suddenly, after a love marriage, I was told to wear a burqa and dedicate myself to domestic work. I became a mother suffering from postpartum depression at 29”.

In the another interview to The Week magazine, she spoke of how she was forced to live a life confined within the four walls of her house.

Then, a shocking act of defiance set her free.

“Once, in a fit of despair, I poured white petrol on myself, intending to set myself on fire. Thankfully, he [the husband] sensed it in time, hugged me, and took away the matchbox. He pleaded with me, placing our baby at my feet saying, ‘Don’t abandon us’,” she told the magazine.

What does Banu Mushtaq write about?

In Heart Lamp, her female characters mirror this spirit of resistance and resilience.

“In mainstream Indian literature, Muslim women are often flattened into metaphors — silent sufferers or tropes in someone else’s moral argument. Mushtaq refuses both. Her characters endure, negotiate, and occasionally push back — not in ways that claim headlines, but in ways that matter to their lives,” according to a review of the book in The Indian Express newspaper.

Mushtaq went on to work as a reporter in a prominent local tabloid and also associated with the Bandaya movement – which focussed on addressing social and economic injustices through literature and activism.

After leaving journalism a decade later, she took up work as a lawyer to support her family.

In a storied career spanning several decades, she has published a copious amount of work; including six short story collections, an essay collection and a novel.

But her incisive writing has also made her a target of hate.

In an interview to The Hindu newspaper, she spoke about how in the year 2000, she received threatening phone calls after she expressed her opinion supporting women’s right to offer prayer in mosques.

A fatwa – a legal ruling as per Islamic law – was issued against her and a man tried to attack her with a knife before he was overpowered by her husband.

But these incidents did not faze Mushtaq, who continued to write with fierce honesty.

“I have consistently challenged chauvinistic religious interpretations. These issues are central to my writing even now. Society has changed a lot, but the core issues remain the same. Even though the context evolves, the basic struggles of women and marginalised communities continue,” she told The Week magazine.

Over the years Mushtaq’s writings have won numerous prestigious local and national awards including the Karnataka Sahitya Academy Award and the Daana Chintamani Attimabbe Award.

In 2024, the translated English compilation of Mushtaq’s five short story collections published between 1990 and 2012 – Haseena and Other Stories – won the PEN Translation Prize.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.