President Donald Trump says he has been seriously talking with Navy Secretary John Phelan about adding “battleships” with gun-centric armament and heavily armored hulls back into America’s naval force structure. There are immediate questions about the feasibility and practicality of the Navy fielding any sort of battleship, a type of vessel the service has not had in its active inventory since 1992. At the same time, Trump’s comments do touch on real questions about the future of naval guns for major surface warships, especially amid ongoing work globally on railguns, and the potential value of added armor to respond to threats, including cruise missiles and drones.

Trump talked about the prospect of a new battleship for the Navy at an unprecedented all-hands meeting of top U.S. military officers at the Marine Corps’ base in Quantico, Virginia, yesterday. War Secretary Pete Hegseth had called for the gathering and had addressed the attendees first.

“I think we should maybe start thinking about battleships,” Trump said, adding that he had spoken to Secretary Phelan on the matter. “Some people would say, ‘No, that’s old technology.’ I don’t know. I don’t think it’s old technology when you look at those guns.”

“It’s something we’re actually considering, the concept of battleship, nice, six-inch side, solid steel. Not aluminum, aluminum that melts. If it looks at a missile coming at it, [it] starts melting as the missile’s about two miles away,” he continued. “Now those ships, they don’t make them that way anymore, but you look at it, your Secretary [Phelan] likes it, and I’m sort of open to it. And bullets are a lot less expensive than missiles.”

“It’s something we’re seriously considering,” he reiterated.

It is unclear if Trump was talking about attempting to recommission any of the four ex-Iowa class battleships, which are preserved as museum ships at various locations around the United States, or building new ones. How seriously the Navy is or isn’t looking at a future battleship force of any kind is also not clear.

“The Navy is committed to maintaining a modern and effective fighting force. An updated Battle Force Ship Assessment and Requirements review has been initiated in alignment with the forthcoming National Defense Strategy,” a Navy official told TWZ when asked for more information. “This work is about fielding the right capabilities, with the right numbers and in the right theater. Once force structure decisions are finalized, they will be announced publicly and executed with speed. Until then, internal deliberations will not be previewed.”

The Navy uses the term “Battle Force” to collectively refer to its fleets of aircraft carriers, submarines, major surface combatants, and amphibious warfare ships, as well as combat logistics vessels and some other types of auxiliaries.

In response to additional queries on the matter, the Office of the Secretary of War also redirected us to the Navy.

This is not the first time that Trump has put forward a version of the battleship proposal. A decade ago, speaking from the deck of the former USS Iowa, then-candidate Trump raised the prospect of recommissioning that ship into service should he be elected. Trump won that election, but Iowa remained berthed in the Port of Los Angeles in California, where it still sits today.

On a level, the idea of recommissioning the Iowas reflects past precedent. These were the last battleships built for the Navy, and their main armament initially consisted of nine 16-inch guns, three in each of three turrets, which could hit targets up to around 23 miles away. Each one also had 20 five-inch guns spread across multiple turrets, along with other weapons. The four ships in the class – the USS Iowa, USS New Jersey, USS Missouri, and USS Wisconsin – were first commissioned into service between 1943 and 1944, and they all served during World War II in the Pacific.

Iowa, New Jersey, and Wisconsin were then decommissioned between 1948 and 1949 as part of post-war drawdowns. Two more ships in the class that were still under construction when Japan surrendered were scrapped entirely.

The Navy recommissioned Iowa, New Jersey, and Wisconsin between 1950 and 1951 to serve in the Korean War. All three of those battleships, along with the USS Missouri, were subsequently decommissioned before 1960. New Jersey briefly returned to service once more between 1968 and 1969, taking part in the Vietnam War.

In the 1980s, under President Ronald Reagan, the four Iowas were put through a deep overhaul and upgrade program before being recommissioned yet again. The modifications most notably included launchers for as many as 32 Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles and up to 16 Harpoon anti-ship missiles, something worth emphasizing in light of Trump’s remark that “bullets are a lot less expensive than missiles.” At that time, the ships also received new radars, electronic warfare systems, and other improvements, including Mk 15 Phalanx close-in defensive gun systems.

Until Ticonderoga class cruisers with 122 Mk 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) cells, as well as upgraded Spruance class destroyers with 61-cell Mk 41 arrays, began entering service in the late 1980s, the modified Iowa design had the largest Tomahawk load of any single ship in the Navy’s inventory.

The four battleships continued to serve through the end of the Cold War, before being decommissioned between 1990 and 1992. Missouri and Wisconsin remained in service just long enough to take part in the Gulf War.

In 2015, there was a case to be made, albeit already increasingly remote, that recommissioning at least some of the Iowas one more time might have been feasible. The former Missouri and New Jersey had been stricken from the Navy’s rolls in 1995 and 1999, respectively, but Iowa and Wisconsin remained in mothballs until 2006. After that, they were turned into floating museums, but Congress only allowed that to happen with the express understanding, enshrined in law, that the U.S. military could ask for them back should the President invoke certain provisions of the National Emergencies Act. In 2007, legislators further clarified that this meant, among other things, that “spare parts and unique equipment, such as 16-inch gun barrels and projectiles, if donated,” could also “be recalled if the battleships are returned to the Navy in the event of a national emergency.”

A debate about the need, or lack thereof, for naval gunfire support to aid in future amphibious operations had been a central factor in the decision to keep the ships in a regenerative state. This was also later tied into the fate of the Zumwalt class stealth destroyers, also known as DDG-1000s, which we will come back to later.

A decade on now, the prospective cost and time to get any of the former Iowa class battleships serviceable again can only have increased, and likely dramatically so. Rehabilitating their now thoroughly dated steam-powered propulsion systems and training personnel to operate them would present particular challenges. TWZ touched on similar issues years ago amid discussions about recommissioning the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk, which first entered service in 1961. The Navy ultimately decided to scrap Kitty Hawk, as well as the ex-USS John F. Kennedy, another ship in its class that had been in mothballs for years.

No country in the world is currently building new warships of a size and with a configuration in line with traditional battleships. Any attempt to do so in the United States would be very costly and manpower intensive. At the end of their final resurrections, the Iowas had over 1,500 crewmen aboard. That is well over five times the crew size of a Arleigh Burke class destroyer. Even assuming automation could cut that number down, making a very large crew commitment to a single surface combatant would be problematic for a Navy that has had trouble in the past meeting recruiting goals.

Beyond all this, in the context of modern naval warfare, there are glaring questions about the basic utility of a very large surface combatant, which would also require a large crew, and that devotes much of its available volume to relatively short-ranged guns. Operating ships like this on a day-to-day basis would be extremely costly and could be otherwise complicated for a U.S. Navy that has struggled to sustain the fleets it has now.

A gun-centric ship would also need to get in very close proximity to use those weapons against any targets at a time when the reach of adversary anti-access and area denial capabilities is only growing. This would only further narrow the scope of operations it could undertake, given that it could easily find itself vastly outranged in many circumstances by threats at sea, ashore, and/or in the air. Such a vessel would already be an obvious high-value target for enemy forces, which would create challenges for more independent operations outside of a larger surface action group.

The future of the very kinds of amphibious operations where naval gunfire support could be most of use is increasingly in question. Since 2020, the U.S. Marine Corps has been engaged in a complete overhaul of force structure centered on new concepts of operations that put significantly less emphasis on deploying via traditional large amphibious warfare ships.

Trump’s comment yesterday that ammunition for naval guns is cheaper per round than a missile is accurate, but this reality does not exist in a vacuum. Missiles have become the dominant naval weapons on larger surface combatants worldwide for attacking targets at sea and on land, as well as in the air, in large part because of the vastly longer reach and precision that they offer over even very large caliber guns. Major surface warships in service today, including in the U.S. Navy, do still typically feature at least one general-purpose main gun, but with a decidedly secondary role to their missile magazines, although these are far smaller than the Iowa class’ main guns. They also generally have arrays of other smaller guns, but for close-in defense.

It is worth noting here that top Navy officials have talked in the past about the need to think about future surface warfare plans outside of the lens of total missile launch capacity, especially as the service’s fleets have contracted in size. A key driver in those discussions has been how to fill the gaps that will come from the retirement of the last of the Ticonderoga class cruisers, now set to come at the end of the decade, which will take hundreds of VLS cells out of service. That being said, large caliber guns historically associated with battleships have not been discussed as any kind of alternative.

Concepts for battleship-like arsenal ships packed with VLS cells, which might also have some degree of secondary gun armament, have been put forward in the past. This rebalancing of capabilities could help just their cost.

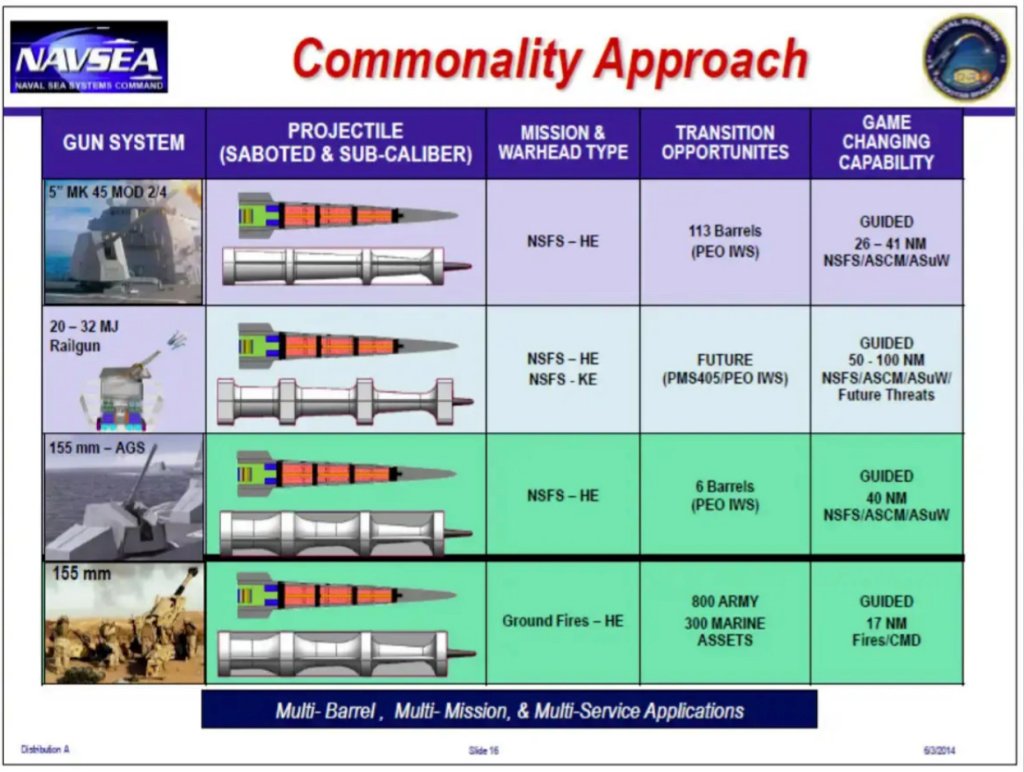

We have seen some of this debate play out already in a way with regard to the Zumwalt class stealth destroyers. A pair of 155mm Advanced Gun Systems (AGS) tucked away inside stealthy turrets, and coupled with specialized long-range rounds, were core features of the finalized DDG-1000 design explicitly intended to meet continued demand for naval gunfire support.

However, the intended ammunition from the AGSs became so costly that the Navy decided not to buy any, rendering the AGSs effectively dead weight. The service is now in the process of stripping at least one of the turrets from each of the three DDG-1000s in order to refit them with the ability to launch Intermediate-Range Conventional Prompt Strike (IRCPS) hypersonic missiles.

Defense spending drawdowns immediately following the end of the Cold War led the Navy to severely truncate its overall plans for the Zumwalt class, overall. This is why only three of the ships were ever built, one of which still has yet to be commissioned into service. The DDG-1000 program has seen major cost and significant technical issues amid persistent questions about the expected roles and missions of these ships. The USS Zumwalt, the USS Michael Monsoor, and the future USS Lyndon B. Johnson are all currently assigned to a unit charged primarily with research and development and test and evaluation tasks. How much it will cost to keep this tiny fleet of exotic ships operational remains a burning question.

There is a line of development that could offer significant new capability in the naval gun space: railguns. Weapons of this type, which use electromagnets rather than chemical propellants to launch projectiles at very high speeds, hold the promise of offering a new and flexible way to rapidly engage targets at sea, on land, and in the air, and do so at considerable ranges for a gun. Railguns also offer magazine depth and cost-per-round benefits over missiles.

Between 2005 and 2021, the Navy was actively working toward an operational railgun capability. The estimated unit cost of the rounds for that weapon was pegged at around $100,000. In addition to being cheaper than missiles, this was also much less pricey than the rounds the Navy had been developing for the guns on the DDG-1000s, which had soared to some $800,000 per shell before that effort was axed.

The Navy halted work, at least publicly, on its prototype naval railgun in the early 2020s, citing technical hurdles. Planned at-sea testing had been repeatedly pushed back at that point. Development of the ammunition has continued for use in existing 5-inch naval guns, as well as weapon systems on land.

Other countries, including China, have also been pursuing this capability in recent years. Just this year, Japan has made significant strides in this realm, as TWZ has been following closely. This might presage the coming introduction of a new category of gun-armed naval vessels, which some experts and observers have quipped to be something of a second coming of the battleship.

Trump’s remarks yesterday also touched on the fact that battleships like the Iowa class offered a higher degree of physical armor protection than is found on modern surface combatants. In particular, battleships were historically characterized by thick armor ‘belts’ along the outside and/or on the interior of the hull above and below the waterline. The main belts on the Iowas, made of steel, were 13.5 inches thick, and they also had extensive armoring elsewhere.

Though it is also not clear what the President was necessarily referring to specifically when he mentioned “aluminum,” those comments do reflect a still-ongoing debate when it comes to the construction of naval warships. Aluminum and aluminum alloys offer certain advantages in naval shipbuilding, particularly when it comes to weight and cost. However, there has been much discussion over the years about their relative durability, as well as their lower melting point and fire resistance compared to available steels.

Persistent cracking on the aluminum superstructures on Ticonderoga class cruisers played a real role in the Navy’s decision to insist on all-steel construction for the Arleigh Burke class of destroyers. The service’s all-aluminum Independence class Littoral Combat Ships have notably suffered from cracking over the years, as well.

Whether it means battleship-like protection or not, there is a case to be made for renewed focus on passive armoring of surface warships as the maritime threat ecosystem continues to expand and evolve. A modern take on the armor belts of traditional battleships could provide valuable additional layers of defense against anti-ship cruise missiles, including types with specially designed penetrating warheads.

Even more limited additional armor could also provide useful extra protection against attacks involving lower-tier weapons, especially one-way attack drones, which are in increasing use, even by non-state actors. Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen have shown how dangerous drones can be to ships at sea, especially if they are layered in with cruise and ballistic missiles and other munitions. The Houthis have also demonstrated how much pressure this puts on the missile magazines on modern warships. Those threats would only be magnified in higher-volume attacks in any future high-end conflict, such as one on the Pacific against China.

Added battleship-like armor may be effective in shrugging-off many types of anti-ship missile attacks, but it would still have its limits, especially against anti-ship ballistic missiles capable of drilling down into hardened targets from directly above just as a byproduct of the high speeds they reach in the terminal phase of their flights. Any extra armoring would require many design trades and considerations. The added mass would require larger propulsion and mechanical support systems, which would then push the ship to be even larger and more complex. Speed requirements could be relaxed although presumably the ship would have to keep-up with a carrier strike group, which would require it to meet or exceed the speeds of other ships designed to do so.

The U.S. Navy is in the process now of devising the requirements for its next surface warship, a future destroyer currently referred to as DDG(X). There are few things more central to the design of a naval vessel than what armament it should have and what materials should be used in its construction.

At the very end of last year, the Navy turned some heads with pictures from a ceremony marking the end of Capt. Matt Schroeder’s time as head of the DDG(X) program office, and Mr. Jim Dempsey’s taking over of that role. A cake at the event featured a rendering of the ship with no main gun at all on the bow, something that had been present in previous official artwork. Though it was just a cake, there is no indication that the source image came from an unofficial source. The Navy also does not appear to have clarified since then whether or not this reflects a design concept currently under consideration.

Beyond battleships, President Trump has also taken a very vocal interest in Navy ship design, in general, over the years, which could have other impacts on the service’s plans. At the tail-end of his first term, the President said he had personally intervened to turn the design of the Constellation class frigate from “a terrible-looking ship” into “a yacht with missiles on it.”

“I’m not a fan of some of the ships you do. I’m a very aesthetic person, and I don’t like some of the ships you’re doing, aesthetically,” Trump said during another portion of his remarks just today. “They say, ‘Oh, it’s stealth.’ I say that’s an ugly ship.”

Even before he was confirmed to his post, Navy Secretary Phelan had said Trump was also texting him in the middle of the night to complain about what is commonly called “running rust” on American warships.

In 2017, Trump had also suggested that the Navy should ditch electromagnetic catapults for launching aircraft on its Ford class aircraft carriers and go back to using steam-powered types. The Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) has been plagued by issues over the years, which the Navy has spent considerable resources working to mitigate.

All of this comes as the Navy continues to struggle, broadly, with acquiring and fielding new warships and otherwise modernizing its fleets, as well as sustaining the vessels in its inventory already. The Constellation class frigate program, which is already three years behind schedule and on track to deliver the first ship nearly a decade after awarding the initial contract, has become a particular poster child for these failings. Constellation was supposed to reduce risk and keep costs relatively low by using an in-production design as a starting point, but the ship now only has around 15 percent commonality with its ‘parent,’ the Franco-Italian Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM), as you can read more about here.

“All of our programs are a mess, to be honest,” Secretary Phelan told members of Congress during a hearing back in June. “Our best-performing one [program] is six months late and 57 percent over budget.”

The Trump administration and Congress have pushed to try to reverse these trends in recent years, including by working to incentivize U.S. shipbuilders and exploring how foreign companies might be able to assist. The Navy has also put increasing emphasis on acquiring larger numbers of smaller vessels, including multiple tiers of uncrewed types, to help bolster its capabilities and operational capacity, while also maximizing available resources. In the meantime, China, in particular, has been surging ahead in naval warship production, as well as the expansion of its capacity to build those vessels, something TWZ has been sounding the alarm on for some time now.

It’s also important to remember that Trump often makes grand pronouncements about potential future military acquisition efforts that do not come to fruition.

Still, while the idea of the Navy operating battleships again is extremely remote, Trump’s influence could emerge in other ways in the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, especially as DDG(X) evolves.

Contact the author: [email protected]