Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

Among the week’s new releases is “The Smashing Machine,” written and directed by Benny Safdie and starring Dwayne Johnson as Mark Kerr, an early mixed-martial-arts fighting champion who saw his career flame out before the sport became a lucrative cultural phenomenon.

Safdie is known for the movies he made with his brother Josh, such as “Good Time” and “Uncut Gems,” and more recently created the series “The Curse” with Nathan Fielder. Safdie won the directing prize at the Venice Film Festival for “The Smashing Machine,” his first solo feature.

Dwayne Johnson in the movie “The Smashing Machine.”

(A24)

In her review of the film, Amy Nicholson wrote about Safdie and Johnson, noting, “These two high-intensity talents, each with something to prove, seem to have egged each other on to be exhaustingly photorealistic. Johnson, squeezed into a wig so tight we get a vicarious headache, has pumped up his deltoids to nearly reach his prosthetic cauliflower ears. And Safdie is so devoted to duplicating the earthy brown decor of Kerr’s late-’90s nouveau riche Phoenix home that you’d think he was restoring Notre Dame.”

I spoke to Safdie earlier this week. He explained how he and Kerr held each other’s hands during the film’s emotional premiere screening at Venice and what it has meant for them to go through the process of seeing through the project together.

“I wanted him to feel some kind of ownership of the movie and his life. And it was very meaningful to me,” says Safdie of Kerr. “Now I hear him talk about it and it’s very interesting because he can say, ‘Oh, I see where I made mistakes in that relationship.’ And he can take ownership of them. And part of it is I wanted to make a movie about somebody’s perspective on life changing.”

A celebration of Jafar Panahi

A scene from the movie “It Was Just an Accident.”

(Neon)

The American Cinematheque is launching a tribute series to Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi this week. Winner of the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival for the dramatic thriller “It Was Just an Accident,” Panahi has become Iran’s most high-profile dissident filmmaker, having been repeatedly jailed, placed under house arrest and officially banned from making films.

Yet none of that has stopped him. Panahi is now one of only four filmmakers ever to win the Palme d’Or, Berlin’s Golden Bear and Venice’s Golden Lion, alongside such giants as Michelangelo Antonioni, Robert Altman and Henri-Georges Clouzot. And “Accident” has been selected to be France’s entry for the international feature Oscar race.

Panahi was scheduled to appear at three events in Los Angeles next week as part of the tribute, but he may not make it. His appearances at the New York Film Festival (now in progress), including a scheduled talk with Martin Scorsese, had to be canceled due to a delay in Panahi receiving his visa to enter the country, reportedly a result of the federal government shutdown.

Even if Panahi does not make it to L.A., his films will play on and deserve to be seen. “Accident” will screen in a double-bill with 2003’s “Crimson Gold” at the Aero on Tuesday. On Wednesday, Panahi’s 1995 debut feature “The White Balloon,” co-written with Abbas Kiarostami, will play in 35mm at the Los Feliz 3. Later on Wednesday at the LF3, Panahi’s 2000 drama “The Circle” will screen in a 35mm print from the Yale Film Archive, along with the 2010 short “The Accordion.”

In 1996, Kenneth Turan had this to write about “The White Balloon”: “A completely charming, unhurried slice of life, it is both slow and sure-handed as it follows a small but fearsomely determined little girl on her amusing search for just the right ceremonial goldfish for her family’s new year’s celebration.”

Discussing “The Circle” in 2001, Turan said, “Restrained yet powerful, devastating in its emotional effects, ‘The Circle’ is a landmark in Iranian cinema. By combining two things that are relatively rare in that country’s production — unapologetically dramatic storytelling and an implicit challenge to the prevailing political ideology — this new film by producer-director Jafar Panahi creates a potent synthesis.”

With or without Panahi in attendance, these are deeply necessary films that speak to their respective moments — and all too much to our current one.

‘All the President’s Men’ and remembering Robert Redford

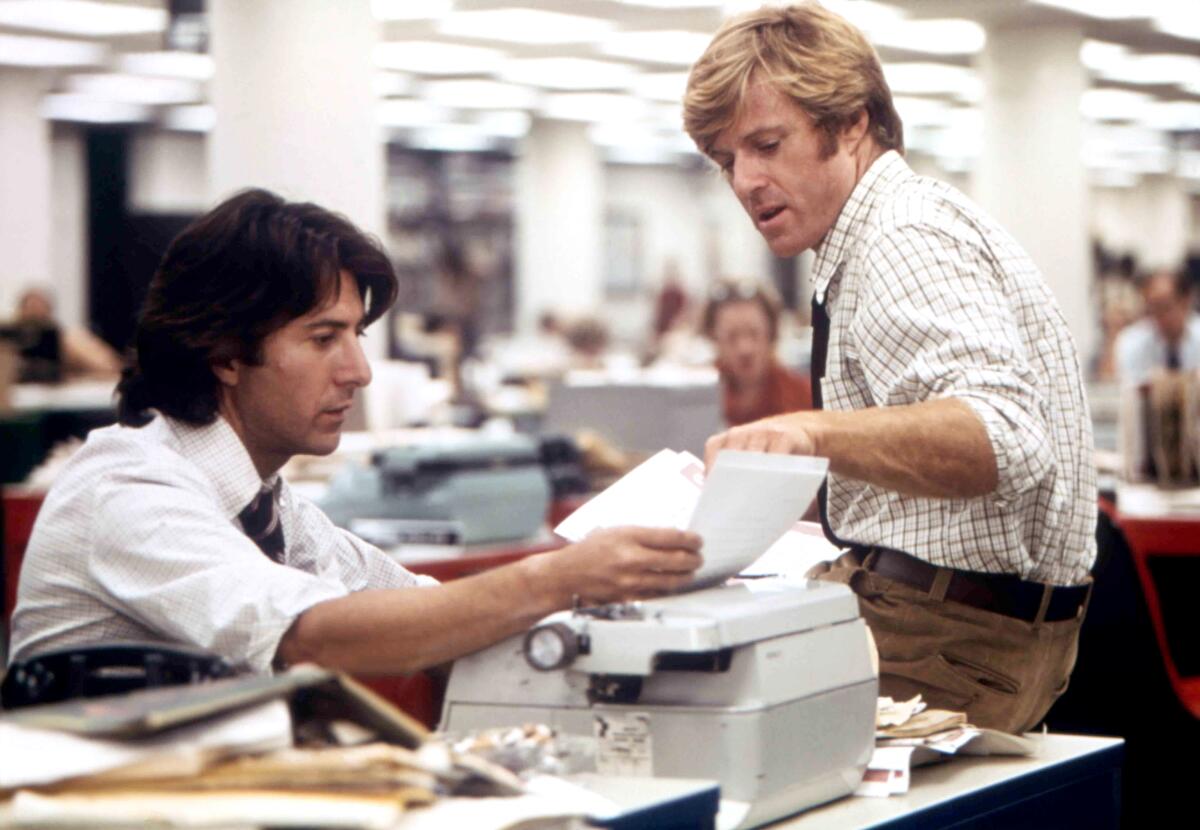

Robert Redford, right, and Dustin Hoffman in the movie “All the President’s Men.”

(Sunset Boulevard / Corbis via Getty Images)

Screenings have already begun to pop up in tribute to Robert Redford, who died recently at age 89. On Friday, Vidiots will screen Alan J. Pakula’s 1976 political thriller “All the President’s Men” in 35mm along with Phil Alden Robinson’s 1992 caper comedy “Sneakers.” On Sunday, Vidiots will also show Sydney Pollack’s 1973 romantic drama “The Way We Were.” (The Academy Museum will screen “The Way We Were” on Oct. 26.)

The American Cinematheque will also be a launching a Redford tribute series starting on Monday with a screening of Tony Scott’s 2001 thriller “Spy Game.” Other films currently scheduled include “Jeremiah Johnson,” “The Sting,” “Three Days of the Condor,” “Indecent Proposal,” “Sneakers” and a 35mm showing of “All the President’s Men.” That barely scratches the surface of Redford’s work as an actor, let alone as a director, so more events are likely to come.

Redford was deeply involved in bringing “All the President’s Men” to the screen as quickly as possible following the Watergate scandal. Writing about “All the President’s Men” in 1976, Charles Champlin said the film has “a clarity born of historical perspective but also a newly quickened feeling of national concern. The central drama and suspense of ‘All the President’s Men’ is a reminder of the narrow margin of our safety and how close the coverup came to working. … The film invites no comfort. It was a narrow and almost accidental escape and the weight of a corrupted government had been tilted against the truth as never before. But never again? The movie makes no preachment but you are bound to think anew that forgiveness and forgetfulness ought to be two starkly different commodities.”

Points of interest

‘Rosemary’s Baby’ in 35mm

Mia Farrow in the 1968 horror landmark “Rosemary’s Baby.”

(Criterion Collection)

“Rosemary’s Baby,” a 1968 adaptation of the novel by Ira Levin written and directed by Roman Polanski (and produced by exploitation impresario William Castle), is still considered one of the creepiest movies of all time. The film stars Mia Farrow as Rosemary Woodhouse, who has moved into a grand old apartment building in New York City with her actor husband, Guy (John Cassavetes). After she becomes pregnant, it begins to seem as if her nosy neighbors have been part of a coven of witches scheming to give birth to the son of Satan. Ruth Gordon won a supporting actress Oscar for her role as one of the neighbors. The movie plays in 35mm Tuesday through Thursday at the New Beverly.

Even back in 1968, the film touched off a nerve with reviewers, including our own. In his original June 1968 review, Champlin wrote, “Having paid my critical respects, I must then add that I found ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ a most desperately sick and obscene motion picture whose ultimate horror — in my very private opinion — was that it was made at all. It seems a singularly appropriate symbol of an age which, believing in nothing, will believe anything. … It is also all so sleazy and sick at heart. And the horror is that it presumes we are too indifferent to perceive what its horrors really are.”

‘The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie’

An image from Luis Buñuel’s “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.”

(Rialto Pictures)

Winner of the Oscar for international feature film and nominated for original screenplay, 1972’s “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” was directed by Luis Buñuel, who wrote the script with Jean-Claude Carrière. Screening at the Academy Museum as part of a series dedicated to Buñuel, the film is a bold satire of societal conventions — one that still largely holds up, as a group of friends meets for a series of meals.

In a November 1972 review, Charles Champlin wrote, “Watching a Buñuel film is a special experience because he creats a special world, somewhere west of hard reality but dealing — mockingly — with social reality and always reflecting Buñuel’s almost puritanical rage at any misuse of power, fiscal, political, ecclesiastical, military, social. … The surrealist attack sometimes makes him sound more formidable that he is. In fact he’s a sly humanist who has here created one of his most easily enjoyable works.”

In other news

PTA, ranked

Joaquin Phoenix in the movie “Inherent Vice.”

(Wilson Webb / Warner Bros.)

Last week, we mentioned Paul Thomas Anderson’s “One Battle After Another,” which Amy Nicholson declared “fun and fizzy.” So this week, I set about the popular task of placing the new film within a ranking of Anderson’s 10 feature films, from his 1996 feature debut “Hard Eight” onward.

As I noted in the introduction, “More so than with other directors, it’s always tempting to overly psychologize Paul Thomas Anderson’s films, looking for traces of his personal development and hints of autobiography: the father figures of ‘Magnolia’ or ‘The Master,’ the partnership of ‘Phantom Thread,’ parenthood in the new ‘One Battle After Another.’ Yet two things truly set his work apart. There’s the incredibly high level of craft in each of them, giving each a unique feel, sensibility and visual identity, and also the deeply felt humanism: a pure love of people, for all their faults and foibles.

“Anderson is an 11-time Academy Award nominee without ever having won, a situation that could rectify itself soon enough, and it speaks to the extremely high bar set by his filmography that one could easily reverse the following list and still end up with a credible, if perhaps more idiosyncratic ranking. Reorder the films however you like — they are all, still, at the very least, extremely good. Simply put, there’s no one doing it like him.”

Would you have a different title at No. 1? Let us know in the comments.