After conducting an investigation into Los Angeles County’s faulty emergency alerts during the deadly January wildfires, U.S. Congressman Robert Garcia issued a report Monday calling for more federal oversight of the nation’s patchwork, privatized emergency alert system.

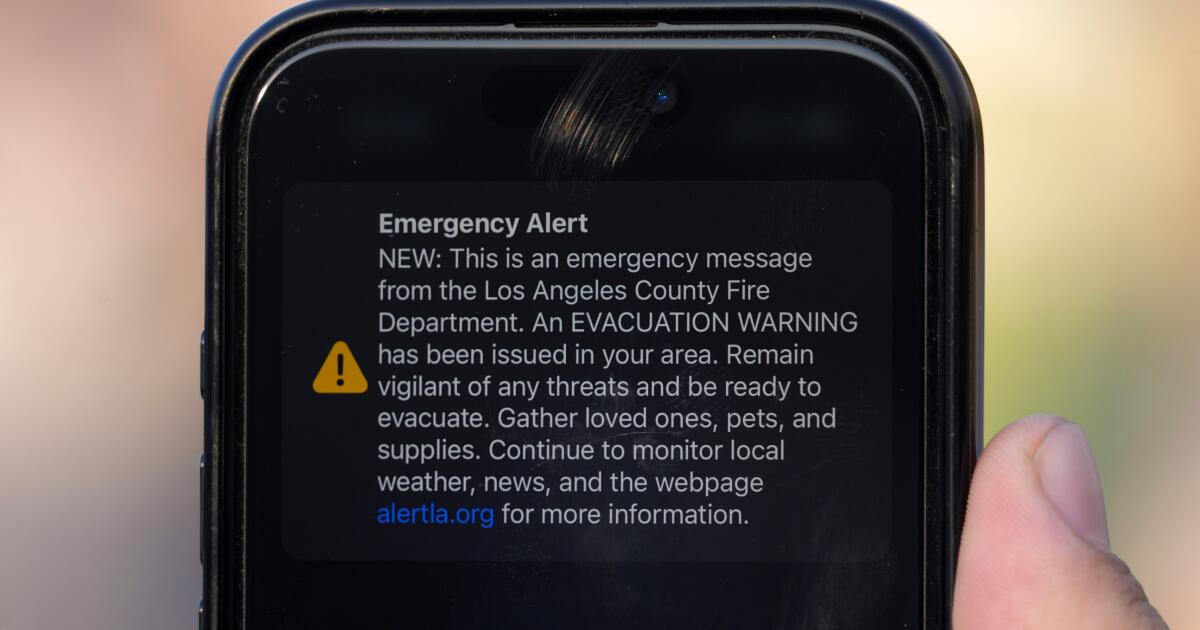

The investigation was launched by Garcia and more than a dozen members of L.A.’s congressional delegation in February after L.A. County sent a series of faulty evacuation alerts on Jan. 9, urging people across a metropolitan region of 10 million to prepare to evacuate. The faulty alerts came two days after intense firestorms erupted in Pacific Palisades and Altadena.

The alerts, which were intended for a small group of residents near Calabasas, stoked panic and confusion as they were blasted out repeatedly to communities as far as 40 miles away from the evacuation area.

The new report, “Sounding the Alarm: Lessons From the Kenneth Fire False Alerts,” alleged that a technical flaw by Genasys, the software company contracted with the county to issue wireless emergency alerts, caused the faulty alert to ping across the sprawling metro region.

It also found that, contrary to accounts of L.A. County officials at the time, multiple echo alerts then went out as cellphone providers experienced overload due to the high volume and long duration of the alerts. Confusion was compounded, the report said, by L.A. County’s vague wording of the original alert.

“It’s clear that there’s still so much reform needed, so that we have operating systems that people can rely on and trust in the future,” Garcia told The Times.

The Times was reaching out to Genasys and county officials for response to the report.

A Long Beach Democrat who sits on the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Garcia said the stakes were incredibly high.

“We’re talking about loss of life and property, and people’s confidence in our emergency notification systems,” he said. “People need to be able to trust that if there’s a natural disaster, that they’re going to get an alert and it’s going to have correct information, and we have to provide that level of security and comfort across the country.”

To improve emergency warning alert systems, the report urges Congress and the federal government to “act now to close gaps in alerting system performance, certification, and public communication.”

“The lessons from the Kenneth Fire should not only inform reforms,” the report states, “but serve as a catalyst to modernize the nation’s alerting infrastructure before the next disaster strikes.”

The report makes several recommendations. It calls for more federal funding for planning, equipment, training and system maintenance on the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Integrated Public Alert & Warning System, the national system that provides emergency public alerts through mobile phones using Wireless Emergency Alerts and to radio and television via the Emergency Alert System.

It also urges FEMA to fully complete minimum requirements and improve training to IPAWS that Congress mandated in 2019 after the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency sent out a false warning of an incoming missile attack to millions of residents and vacationers. Five years after Congress required “the standardization, functionality, and interoperability of incident management and warning tools,” the report said, FEMA has yet to finish implementing certification programs for users and third-party software providers. The agency plans to pilot a third-party technology certification program this year.

The report also presses the Federal Communications Commission to establish performance standards and develop measurable goals and monitoring for WEA performance, and ensure mobile providers include location-aware maps by the December 2026 deadline.

But the push for greater oversight is certain to be a challenge at a time when President Trump and U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem are pushing for FEMA to be dismantled.

In the last few days, the Trump administration fired FEMA’s acting head, Cameron Hamilton, after he told U.S. lawmakers he does not support eliminating the agency. Noem told U.S. Congress members at a hearing last week that Trump believes the agency has “failed the American people, and that FEMA, as it exists today, should be eliminated in empowering states to respond to disasters with federal government support.”

Garcia described the Trump administration’s dismantling of FEMA as “very concerning.”

“We need to have stable FEMA leadership,” Garcia told The Times. “The recent reshuffling and changes that are happening, I hope, do not get in the way of actually making these systems stronger. We need stability at FEMA. We need FEMA to continue to exist. … The sooner that we get the investments in, the sooner that we complete these studies, I think the more safe people are going to feel.”

Garcia said his office was working on drafting legislation that could address some of these issues.

“We really need to push FEMA and we need to push the administration — and Congress absolutely has a role in making sure these systems are stronger,” Garcia said. “Ensuring that we fully fund these systems is critical. … There’s dozens of these systems, and yet there’s no real kind of centralized rules that are modern.”

According to FEMA, more than 40 different commercial providers work in the emergency alert market. But further steps need to be taken, an agency official said, to train local emergency managers and regulate the private software companies and wireless providers that play a pivotal role in safeguarding millions of Americans during severe wildfires, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods and active shooter incidents.

“Ongoing efforts are needed to increase training with alerting authorities, enhance standardization with service providers, and further collaboration with wireless providers to improve the delivery of Wireless Emergency Alerts to the public,” Thomas Breslin, acting associate administrator of FEMA’s Office of National Continuity Programs, said in a letter to Garcia.

Genasys, a San Diego-based company, said in a recent SEC filing that its “ALERT coverage has expanded into cities and counties in 39 states.” “The vast majority of California” is covered by its EVAC system, it said, which continues “to grow into the eastern United States, with covered areas expanding into Texas, South Carolina, and Tennessee.”

Genasys also noted that its ALERT system is an “interactive, cloud-based” software service, raising the possibility of communication disruption. “The information technology systems we and our vendors use are vulnerable to outages, breakdowns or other damage or interruption from service interruptions, system malfunction, natural disasters, terrorism, war, and telecommunication and electrical failures,” it said in its SEC filing.

As part of its investigation into how evacuation warnings were accidentally sent to nearly 10 million L.A. County residents during the L.A. fires, Garcia received responses from Genasys, L.A. County, FEMA and the FCC.

The report said a L.A. County emergency management worker saved an alert correctly with a narrowly defined polygon in the area near the Kenneth fire. But the software did not upload the correct evacuation area polygon to IPAWS, possibly due to a network disruption, the report said. The Genasys system also did not warn the L.A. County emergency management staffer that drafted the alert a targeted polygon was missing in the IPAWS channel before it sent the message, the report found.

Genasys has since added safeguards to its software, but the report noted that Genasys did not provide details about the incident. . It suggested the independent after-action review into the Eaton and Palisades fire response “further investigate Genasys’ claims of what caused the error, and how a network disruption would have occurred or could have blocked the proper upload of a polygon into the IPAWS distribution channel.”

The report commended L.A. County for responding quickly in canceling the alert within 2 minutes and 47 seconds and issuing a corrected message about 20 minutes later, stating the alert was sent “in ERROR.”

But it also criticized the county’s wording of the original alert as vague. Some confusion could have been avoided, it said, if the emergency management staffer who wrote the alert had described the area with more geographic specificity and included timestamps.

The report also found that a series of false echo alerts that went out over the next few days were not caused by cellphone towers coming back online after being knocked down because of the fires, as L.A. County emergency management officials reported. Instead, they were caused by cellphone networks’ technical issues.

One cellphone company attributed the duplicate alerts to a result of “overload, due to high volume and long duration of alerts sent during fires.” While the report said the company installed a temporary patch and was developing a permanent repair, it is unclear if other networks have enabled safeguards to make sure they do not face similar problems.

The report did not delve into the critical delays in electronic emergency alerts sent to areas of Altadena. When flames erupted from Eaton Canyon on Jan. 7, neighborhoods on the east side of Altadena got evacuation orders at 7:26 p.m., but residents to the west did not receive orders until 3:25 a.m. — hours after fires began to destroy their neighborhoods. Seventeen of the 18 people confirmed dead in the Eaton fire were on the west side.

Garcia told The Times that the problems in Altadena appeared to be due to human error, rather than technical errors with emergency alert software. Garcia said he and other L.A. Congress members were anxious to read the McChrystal Group’s after-action review of the response to the Eaton and Palisades fires.

Local, state and federal officials all shared some blame for the problems with alerts in the L.A. fire, Garcia said. Going forward, Congress should press the federal government, he said, to develop a reliable regulatory system for alerts.

“When you have so many operators and you don’t have these IPAWS requirements in place, that is concerning,” Garcia said. “We should have a standard that’s federal, that’s clear.”

Garcia told The Times that emergency alerts were not just a Southern California issue.

“These systems are used around the country,” he said. “This can impact any community, and so it’s in everyone’s best interests to move forward and to work with FEMA, to work with the FCC, to make sure that we make these adjustments and changes. I think it’s very critical.”

Times staff writer Paige St. John contributed to this report.