Recent populist and left-wing political movements have had a significant impact on Latin American foreign policy. These organizations usually work to promote regional integration and South-South cooperation while opposing a centralized power. As a result, the country’s foreign policy objectives have changed [1], with a greater emphasis now being placed on cultivating links with other countries in the region and developing new economic and political systems.

Populism is an ideological perspective on politics that places a strong emphasis on the needs and preferences of common people. Populist leaders frequently portray themselves as being at odds with the ruling class and established institutions in their nations. By directly appealing to the public and offering to remedy their issues, they hope to win support. In Latin America, where many nations have suffered with poverty, inequality, and political instability, this strategy has been applied frequently.

Hugo Chavez, Lula, Correa, Evo Morales, Nestor, and Cristina Kirchner were among the populist [2] leaders who rose to prominence during the first progressive cycle. Their speeches and criticism of US political influence served as their main foundation. These regimes dismantled the default alignment of governments in Latin America with Washington in addition to enforcing a radical agenda. After so many years of the “Washington Consensus ,”[3] their dizzying language inspired the majority, saving politics as a field of discernment under the broad banner of economic redistribution. These leaders are noted for their captivating personalities and abilities to connect with regular people. They have also enacted measures that aid the poor and oppressed, such as social welfare programs, land reforms, and the nationalization of important enterprises

Populism, on the other hand, has been condemned [4] for its ability to erode democratic institutions and consolidate power in the hands of the leader. Populist leaders have been accused of employing divisive language, stifling opposition, and restricting press freedom. Furthermore, certain populist measures, such as nationalization or protectionism, have been condemned for harming the economy and foreign relations.

When it comes to the causes of this massive shift to the left in current times, we can talk about a generalized discomfort, a social malaise that has been very well capitalized by this political sector, a discourse that makes perfect sense to the average voter and, of course, inclines to vote for this option, a left that has promised a more equitable distribution of wealth, better public services, and, of course, expanded social safety nets.

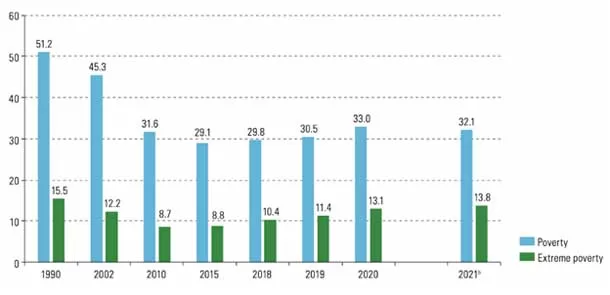

It is not very difficult to recognize that there is the alleged social unrest that the left promises to address; we only need to look at a few social and economic indicators to realize that something is taking place that suggests that things are not going very well, and here we will see some of these indicators in the first place. In case you didn’t know, the region’s economic development has essentially stagnated for the past five years as seen in this graphic. [5]

we must also take into account the recent pandemic, which had terrible repercussions and ramifications for many economies in the area. This has led to a poor economic climate that has many people very frustrated and does not appear to be getting any better. This sign of rising poverty has been intensified by the current epidemic, as you can see below. Since 2015, the continent has seen an increase in both poverty and extreme poverty, which inevitably leads to significant social upheaval. Even in the previous year for the year 2022, poverty rose to 32, 3% [6].

We have an indicator that, despite being hotly debated in terms of importance depending on the political group, is undeniably always in the public debate. In this case, I specifically refer to the Gini coefficient, also known as the inequality index. [7] This indicator shows us that this downward trend in inequality that was maintained for almost 20 years seems to have been broken. That is to say, everything indicates that inequality itself in Latin America appears to be growing, which according to some generates a kind of social networks in last place people as a major cause of this widespread discontent that we are experiencing in the region.

Since it has been abundantly clear from various social and economic indicators that things are not going well, we have the tremendous increase in inflation that you can see here in many countries above 8%,[8] which has not been seen in decades and which, of course, contributes to this great social unrest that we have been talking about. Now that we’ve seen this, we can draw the appropriate conclusions and attempt to address the fundamental question of why the left appears to be expanding so rapidly in this part of Latin America.

On the one hand, we have a population that is completely stagnant, frustrated, and feels like their life is not progressing every time their money can only buy fewer things. On the other hand, there is a political sector and an ideology that offers quick and temporary solutions to this population. The left suggests greater equality and higher taxes.

The problem in all this is that absolutely no one is concerned about the long term, no one of course proposes measures to return to economic growth and of course to bring investment and much less to try to be more competitive, nothing people all that is absolutely the same but rather what they propose are populist and absolutely short-term measures.

There are problems [9] that affect all of Latin America and influence the decisions made by these leftist governments. These governments share some historical responsibility for the high hopes and expectations brought on by their electoral victories, the majority of which were against previous administrations and resulted in significant social and political unrest.

The first is to strengthen their democratic institutions. It remains no secret that Latin American democracies [10] are fragile, and that the authoritarian and illiberal threats that all democracies have been dealing with for a few decades are more dangerous and might potentially inflict more damage in those countries whose democratic institutions and culture are more brittle. By the end of the 20th century, democracies had spread throughout Latin America and achieved significant progress. With the historical exception of Cuba, Latin American political systems based on democracy and the rule of law were established through the overthrow of military coups, the putting an end to armed insurgencies, and the widespread adoption of elections as the only method of political decision-making by their peoples.

The greatest bulwark of democracy in Latin America must be the political left. It must do so because there are still left-wing autocracies and their experiences unfairly burden other parties in other nations. Democracy cannot be used as a tool for revolution since it conceals despotism and oppression. Democracy serves as a goal and a framework; without it, nothing is conceivable, and socialism [11] is compatible. Socialism is, therefore, first and foremost about freedom; in other words, it is impossible to build more just and equal society without freedom.

Democracies, which are particularly targeted by the malignant effects of narco-terrorism, are likewise impacted by security. Freedom is conditioned on security. In Latin America, there is an overwhelming need for security due to the levels of violence and assaults on one’s self-respect. Despite making up only 9% of the global population, the area is responsible for 40% of crimes [12]. 43 of the world’s 50 most dangerous cities are located in Latin America. Several political right politicians won elections on the basis of pledges to wage an “all-out” war against violence, and despite the fact that their promises remained just that—promises—that ideology is seen as being more potent in the struggle for security. This conflict cannot be lost by the left.

The development of the welfare society is the second difficulty. Taxation is without a doubt the foundation for the challenging but also important construction of public benefits. With tax revenues at or below 20% of GDP,[13] excellent healthcare and education cannot be made available to everyone. With 50% of the economy being in the black market, it is also impossible to maintain a system of pensions for old age, sickness, and unemployment. Three of the four pillars of the welfare state have previously been discussed; however, if a fourth pillar were to be added, it would be composed of social services, the struggle against poverty and exclusion, and care for the aged (dependence). For this, tax receipts, including Social Security, must be taken into account.

The social democratic revolution that occurred in Europe in the latter part of the 20th century and that will ultimately take place [14] in Latin America is one that is built on a competitive economy that can produce full employment and enough resources (wages and taxes) to support the social state. It is logical that certain nations in the area (Venezuela and Mexico are prime examples) rely heavily on natural resources for their fiscal revenue, but this income has grown unstable and leads to extremely risky inertial dependencies.

Foreign policy in Latin America has been significantly influenced by left-wing parties. The United States and its policies have often drawn greater criticism [15] from left-leaning administrations, especially when it comes to the region’s effect on the economy and politics. Leaders on the left have frequently pushed for more just economic policies that put social expenditures first and lessen economic inequality.

Finally, the Latin American left must face Latin America’s historic backwardness and failure in regional integration. [16] In various historical instances, these failings are equally due to the right and the left. It is also true that government ideological coherence does not ensure regional convergence, as proven by the fact that numerous integration projects have been laden with ideology, which is precisely what has thwarted them.

These new progressive governments view regional integration as a means to reactivate national economies by opening up to new investments and markets that come with the geopolitical upheavals rather than making lofty Latin Americanist claims as in the first cycle.

How this collaboration will develop is still uncertain. It is questionable whether it is necessary to spend time and money on summits with a strong ideological discourse given the failure of CELAC [17] and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), the main regional integration mechanisms during the first progressive cycle. Instead, it forces each move in this direction to imply practical advancements that prioritize the economic sector and collaborative solutions to specific problems.

Now, when we talk about the new country leaders, we have instances like the former guerrilla combatant and current president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro elected in 2022, is well-known for pushing for greater political and social fairness in Colombia. [18] He has been outspoken in his criticism of the old political elite in the nation, which he claims is corrupt and disconnected from the interests of everyday Colombians. Young people and working-class Colombians who are dissatisfied with the nation’s economic and political inequalities make up a large portion of Petro’s support base.

Colombia has already opened its borders [19] to Venezuela, and closing the gap between the two nations would strengthen regional cooperation since it would have a significant impact on the millions of people who live on the border between the two nations. An entirely new atmosphere of cooperation between Caracas and Bogota will be established as a result of Venezuela’s participation in Colombia’s upcoming peace talks with the National Liberation Army (ELN) [20].

In order to combat poverty and injustice, advance social justice, and safeguard the environment, Petro’s political program contains these initiatives. Additionally, he has been an outspoken opponent of the nation’s protracted battle with armed groups, calling for a negotiated peace agreement that includes expanded political and economic rights for underprivileged groups.

Moreover, the election of the left-wing candidate Gabriel Boric [21] against the representative of the extreme Pinochettist right, José Antonio Kast, in Chile was probably the most significant political event in 2021 in the region. Indeed, the success or failure of his future government will have an impact on the region’s left’s capacity to project a new political cycle.

Boric’s prospective administration faces an unparalleled task in Chile, with the objective of building an eco-feminist government inspired by Salvador Allende’s democratic socialism and consolidating a revolutionary project that sets the groundwork for defeating the neoliberal paradigm. Chile’s economy fared well in 2022, contrary to projections. Boric’s administration established a budget surplus, which had not been seen in the South American country in a decade

The fiscal [22] balance is explained by a major adjustment in public spending following the large outlay made in 2020 and 2021 to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. Significant revenues were also generated by the reactivation of the copper and lithium markets.

Furthermore, in Brazil the election of Lula shows that this new cycle of progressivism [23] is more interested in seeking economic collaboration with all the global power centers than it is in developing geopolitical conflicts.

Under Lula’s presidency in Brazil in 2022, this change in foreign policy priorities will be one of the more notable examples. With his victory in 2022, the socialist politician Lula—who had previously presided over Brazil from 2003 to 2010—came back to power. In 2022, Lula’s foreign policy continued to place a strong emphasis on South-South cooperation and regional integration, with China as a specific priority [24] .

Brazil has become a big supplier of raw commodities over the years, which the Chinese have devoured. In 2009, China surpassed the United States as Brazil’s largest export market, purchasing tens of billions of dollars in soybeans, cattle, iron ore, chicken, cellulose, sugar cane, cotton, and crude oil each year.

During the four years that right-wing Jair Bolsonaro was president of Brazil, ties between the Asian behemoth and the Latin American power were strained. Even some of Bolsonaro’s agriculture backers questioned the outbursts that resulted in enmity with China.

According to Chinese official media,[25] the South American country is already the greatest receiver of Chinese investment in Latin America. And Lula is looking for partnerships that will challenge the predominance of Western-dominated economic institutions and geopolitics.

Conclusion

To be effective, the new leftist authorities will need to devise strategies to overcome the first cycle’s political incapacity in order to make substantial reforms. At the same time, they must recapture the populist spirit that propelled the progressive cycle two decades ago, while also dealing with the consequences of geopolitical upheavals in their own countries.

We do not switch allegiances because the right formerly ruled many of these nations; instead, we vote for the left to see whether they can address all of our issues. Unfortunately, Latin America is a region that alternates between the left and the right on a regular basis, without both a well-defined Core and, obviously, any long-term projects. We can only hope that the day will come when Latin America will propose long-term, sustainable policies that are not populist and that, of course, have an established path. Right now, we want quick populist policies and are willing to make any promise to gain more support.

Nevertheless, Latin American integration will only progress if national interests are discussed openly, free of outdated superstitions and misleading rhetoric. It is not a matter of speculating on Bolivar’s ideal, but of gradually establishing a supranational union, beginning with the most fundamental: a more harmonized market and the removal of old national frontiers to individuals, commodities, merchandise, and services. It is not a matter of resurrecting national flags that have already expired in a more globalized world, but of reclaiming integration as a driver for growth and success.

You must be logged in to post a comment.