The most densely packed section inside the Rose Bowl on Saturday was filled with fans wearing the colors of the visiting team.

Swathed in red and white, they crammed into one corner of the century-old stadium for what amounted to a nightlong celebration.

Fans cheering for the home team were more subdued and scattered throughout a stadium that seemed about one-third full, outnumbered by empty seats, visiting fans and those massive blue-and-gold tarps covering most of each end zone. Deliberately or not, Fox cameras inside the stadium showed those watching from home only wide shots filled with graphics that obscured the paltry crowd.

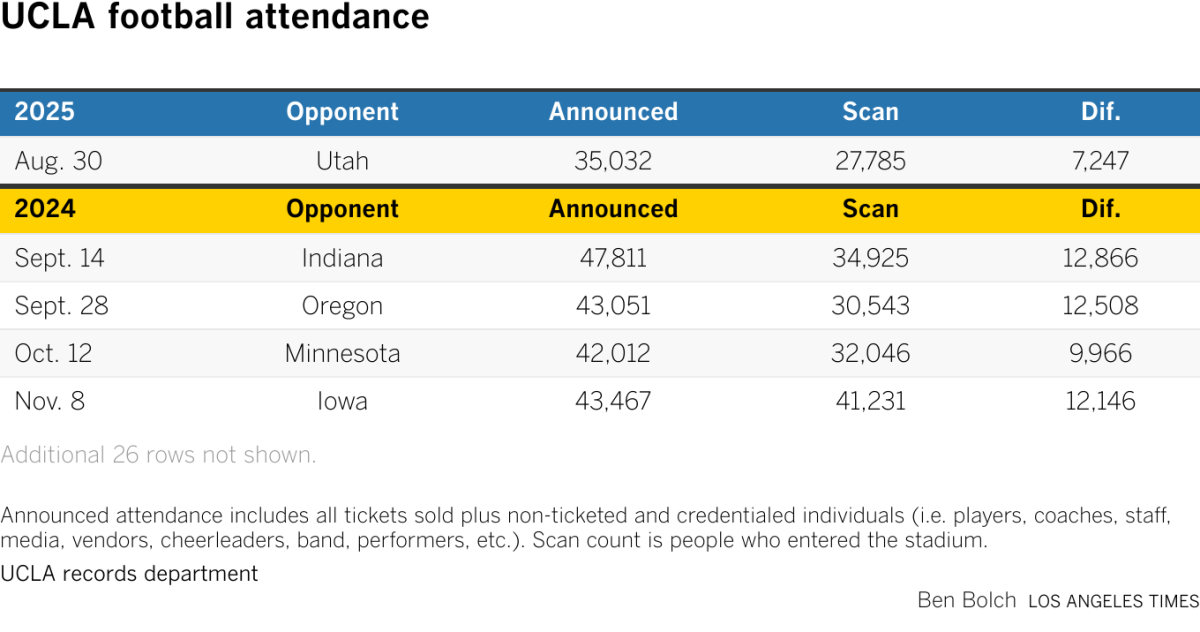

By late in the third quarter, the only suspense remaining in UCLA’s 43-10 blowout loss to Utah was waiting for the announced attendance. Reporters in the press box were given a figure of 35,032, which seemed inflated given so many empty seats below them.

It was.

The scan count, a tally of people actually inside the facility, was 27,785, according to athletic officials.

Creative accounting is the norm in college football given there are no standardized practices for attendance reporting. The Big Ten and other conferences leave it up to individual schools to devise their own formulas.

UCLA defines its announced attendance as tickets distributed — including freebies — plus non-ticketed and credentialed individuals such as players, coaches, staff, vendors, cheerleaders, band members, performers and even media. Across town, USC’s announced attendance includes only tickets distributed, according to an athletic department spokesperson, which was 62,841 for the season opener against Missouri State.

In recent seasons, UCLA’s announced attendance was sometimes more than double the scan count, according to figures obtained by The Times through a public records request.

For UCLA’s home opener against Bowling Green on a sweltering September day in 2022, the announced attendance was 27,143, a record low for the team since moving to the Rose Bowl before the 1982 season.

The actual attendance was much lower. UCLA’s scan count, which represented people who entered the stadium (including the aforementioned non-ticketed and credentialed individuals) was 12,383 — 14,760 fewer than the announced attendance. The scan count for the next game, against Alabama State, was just a smidgen higher at 14,093.

Those longing for an on-campus stadium could quip that UCLA might as well hold some games at Drake Stadium given the track facility holds 11,700 and could probably accommodate several thousand more with temporary bleachers placed opposite the permanent grandstands.

Empty seats aren’t just a game day buzzkill given their correlation to lost revenue.

“Since we are now in the era of NIL and revenue sharing, where cash is king,” said David Carter, an adjunct professor of sports business at USC, “every school hoping to play competitive big-time football needs to generate as much revenue and excitement around its program as possible. But since empty seats don’t buy beer or foam fingers, let alone merchandise and parking, any and all other forms of revenue are needed to offset these chronic game day losses in revenue.”

Declining revenue is especially troublesome at a school whose athletic department has run in the red for six consecutive fiscal years. The Bruins brought in $11.6 million in football ticket revenue during the most recent fiscal year, down nearly half from the $20 million they generated in 2014 when the team averaged a record 76,650 fans at the Rose Bowl under coach Jim Mora. But one athletic official said the school in 2025 could come close to matching the $5.5 million it generated in season ticket revenue a year ago.

Low attendance is a deepening concern. UCLA’s five worst home season-attendance figures since moving to the Rose Bowl in 1982 have come over the last five seasons not interrupted by COVID-19, including 46,805 last season. That figure ranked 16th among the 18 Big Ten Conference teams, ahead of only Maryland and Northwestern, which was playing at a temporary lakeside stadium seating just 12,023.

Recent attendance numbers remind some longtime observers of the small crowds for UCLA games in the late 1970s at the Coliseum, which was part of the reason for the team’s move to Pasadena. During their final decade of calling the Coliseum home, the Bruins topped 50,000 fans only six times for games not involving rival USC.

“Now, disappointingly, it would appear that the same attendance challenges that UCLA football faced at the Coliseum in the 1970s are repeating themselves at the Rose Bowl,” said John Sandbrook, a former UCLA assistant chancellor under chancellor Chuck Young and one of the primary power brokers in the school’s switch to the Rose Bowl.

Attendance woes are hardly confined to UCLA. Sixty-one of 134 Football Bowl Subdivision teams experienced a year-over-year decline in attendance last season, according to D1ticker.com.

UCLA faces several unique challenges, particularly early each season. Its stadium resides 26 miles from campus and students don’t start classes until late September. Other explanations for low turnouts have included late start times such as the 8 p.m. kickoff against Utah, lackluster nonconference opponents and triple-digit heat for some September games.

Quarterback Nico Iamaleava said he appreciated those who did show up Saturday, including a throng of friends and family from his hometown Long Beach.

“Fan base came out and showed their support, man,” Iamaleava said. “You know, it felt great going out there and playing in front of them. Obviously, we got to do our part and, you know, get them a win and make them enjoy the game.”

On some occasions, UCLA’s attendance figures have closely reflected the number of people in the stadium, including high-interest games such as Colorado coach Deion Sanders’ appearance in 2023. For that game, the announced attendance (71,343) only slightly exceeded the scan count (68,615).

The rivalry game also gets fans to show up. The announced attendance of 59,473 last season for USC’s 19-13 victory at the Rose Bowl wasn’t far off from the scan count of 51,588.

See all those empty seats? There were fewer than 13,000 fans in attendance to see quarterback Dorian Thompson-Robinson, right, and wide receiver Titus Mokiao-Atimalala celebrate a touchdown against Bowling Green in 2022.

(Mark J. Terrill / Associated Press)

Still, as traditions go, creative accounting might predate the eight-clap. Similar to fudging practices known to be widespread at other schools, UCLA officials have been known to embellish attendance figures, sometimes rounding far enough past the next thousand not to strain credulity, according to two people familiar with operations who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter.

Additionally, according to a former university administrator who observed the practice, a member of the athletic department staff would show a slip of paper with a suggested attendance figure for basketball games at Pauley Pavilion in the 1960s and 1970s to athletic director J.D. Morgan, who would either nod or take a pen and change the number to one more to his liking. That practice continued under subsequent athletic director Peter Dalis, the administrator said.

While declining to comment for this story, current athletic administrators have acknowledged the challenge of drawing fans in an increasingly crowded sports landscape that now includes two local NFL teams. Among other ventures, UCLA has created a new fan zone outside the stadium that can be enjoyed without purchasing a ticket and will hold a concert on the north side of the stadium the day of the Penn State game early next month.

While there’s no promotion like winning, as the saying goes, there also may be no salvaging the situation for the Bruins’ next home game. UCLA will face New Mexico on Sept. 12 for a Friday evening kickoff that will force fans to fight weekday traffic to see their favorite team face an opponent from the Mountain West Conference.

Brave souls who look around and hear the announced attendance might experience inflation on the rise once more.