Among my many memories of hiking around Southern California, I have a few that haunt me.

The time I got briefly lost around Mt. Waterman, where I’d been several times. When I ran out of water hiking Strawberry Peak on an unseasonably hot day. When I was dressed appropriately for a long day hike until I fell into the river and was uncomfortably cold for the rest of the day. When I thought I was on trail only to realize I was kind of stuck on a steep, unstable hillside.

Each time, I was underprepared. Each bad experience was preventable. That’s the lesson of today’s Wild.

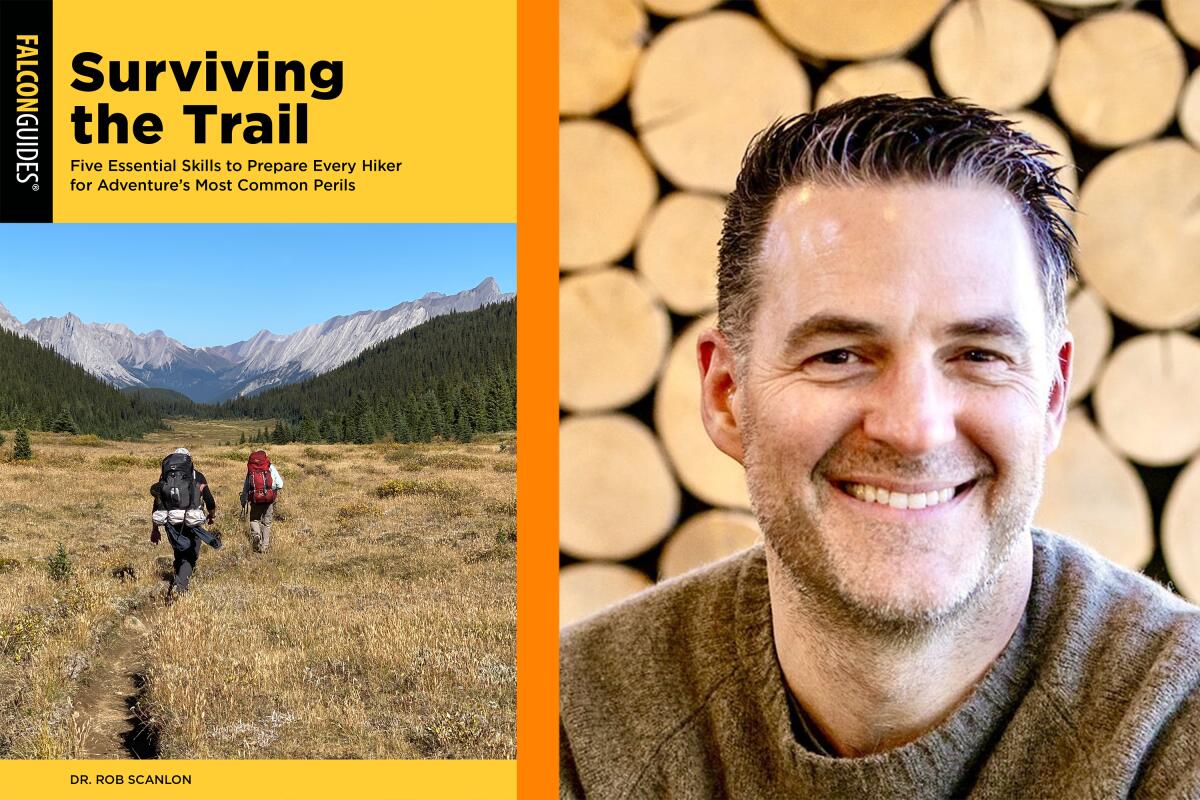

I spoke to Dr. Rob Scanlon, author of the newly published “Surviving the Trail” (Falcon Guides), a guide book that lays out how we can prevent the most common hiking emergencies by slowing down and planning long before we hit the trail.

Scanlon said he sees his work as less of a “hiker safety” book and more of a “hiker empowerment” book.

“I’m hoping people will recognize that this is intrinsically a dangerous place to be,” said Scanlon, who is board certified in internal medicine, pulmonology, critical care and sleep medicine. “Being a little bit anticipatory, and certainly concentrating on the simple things you can control, will really lead to an almost near guarantee that you will not end up the subject of a news headline.”

I never want to write about any of you, dear Wilders, unless it’s to amplify the great work you’re doing in the outdoors. I do, however, want to help us all learn — through a thoughtful, not sensationalist, approach — how we can make the kinds of memories we enjoy reflecting on.

The subtitle to Scanlon’s book is “Five Essential Skills to Prepare Every Hiker for Adventure’s Most Common Perils.” Let’s dive into what those are.

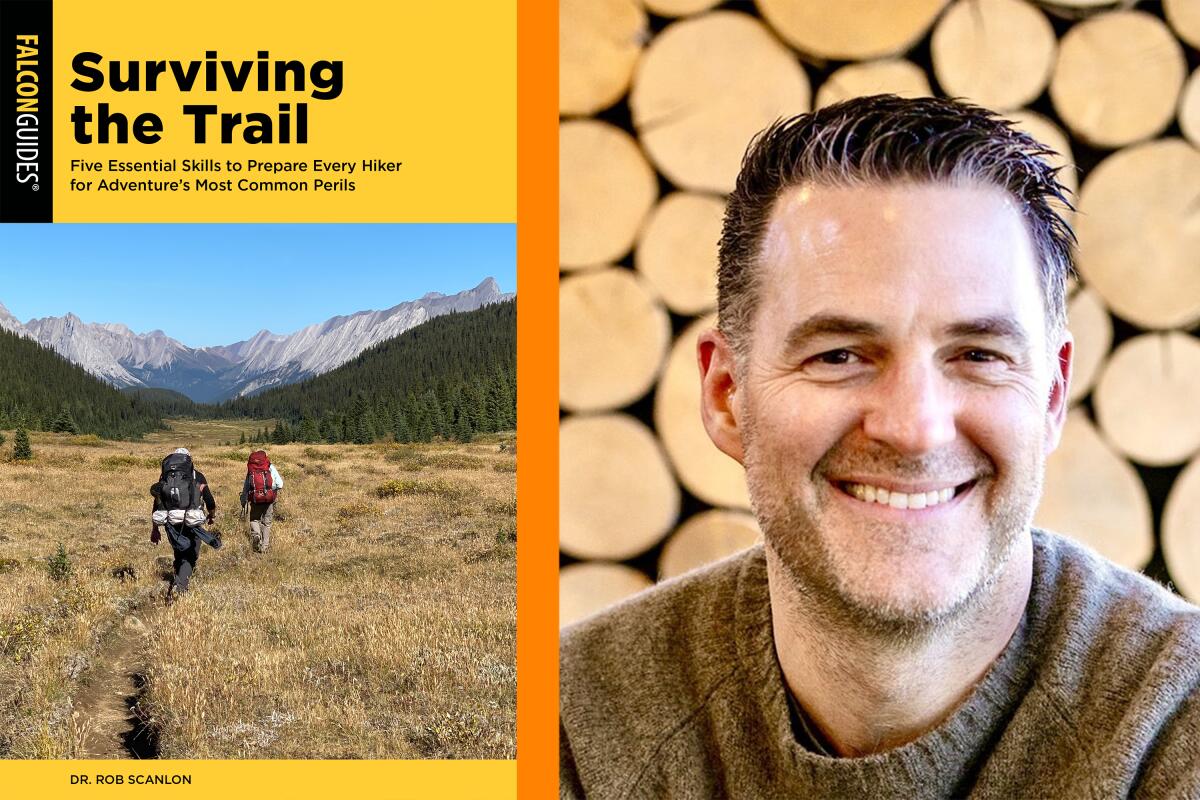

On a hot day, it’s important to stay hydrated, including on hikes that lack shade, like this one in Griffith Park.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

1. Dehydration 🥵

Long before 7-Eleven, Buc-ee’s and (as an Okie, I must mention) QuikTrip, humans had to actually plan for hydration. Today, if you’re out and about and you’re thirsty, there are generally “20 places you could stop within a rock-throwing distance where you could grab something to drink,” Scanlon said. “We’re more acting in real-time in our off-trail lives, not anticipatory like it used to be.”

This mindset can lead to a lack of planning around hydration. And it shows in the data, as Scanlon notes in his book. “Thousands of hikers” require rescue every year because of issues around dehydration, he wrote.

In his book, Scanlon outlines not only how to determine whether you’re dehydrated on the trail but also, arguably more important, how to plan out your fluid needs. The key factors for determining how much water you should pack are: how fast you’ll be hiking, the terrain you’re traversing, the temperatures you’ll encounter and how humid it’ll be.

Scanlon outlines this in a handy chart, which I used to determine I’m generally bringing enough water: about 32 ounces an hour, given I’m going about 2.5 mph, gaining between 1,200- and 2,000-feet elevation and hiking in moderate temperatures.

“I try to stress strategy. Stopping at the local gas station on the way to the trailhead and grabbing a 12- or 16-ounce bottle of [water] is not a strategy,” said Scanlon, who lives in Georgia. “The strategy begins before the hike.”

Wild writer Jaclyn Cosgrove and dog Bonnie enjoy a frolic in the snow near Buckhorn Campground last winter.

(Mish Bruton)

2. Perilous weather ☀️❄️

As we head into colder temperatures here in Southern California — we just got snow in our mountains! — it is crucial to layer appropriately, including with the right materials.

Any hiker has experienced the phenomenon of bundling up at the car and then needing to shed at least one layer at the start of the hike. Scanlon said as we move and generate heat, we need to either shed or open layers, aiming to maintain feeling a little on the cool side.

My favorite cool-weather layering approach is a merino wool base layer with a puffer vest on top. Sometimes I add gloves, but it really depends on the wind temperature. I often wear either fleece-lined hiking pants, especially if I will be around snow, or thick leggings. And I almost always have on these socks, which all my friends are tired of hearing about. In my pack, I carry extra socks and another base layer that I often change into at my destination. I also like to have my rain jacket (with pit vents!) in case it’s windy at the summit.

All of this is informed by one basic thing I do before hiking: I extensively check the weather, which is not always a straight-forward process.

“Most only look at the weather forecast before traveling, but it often changes as hike time approaches and may not apply to whether the hike will actually take place,” Scanlon wrote. “Forecasts often pertain to the conditions in the nearest city center or local airport and not necessarily those in the hiking areas and surrounding mountains.”

Scanlon outlines great resources to be better prepared for mountain conditions, including this website.

Mish, a friend of The Wild, crosses a stream via logs on the Trail Canyon Falls hike.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

3. Crossing rivers and creeks

Drowning is the most common cause of death in national parks, including misunderstanding how to safely swim in or cross a river. Even the experts struggle with that, which emphasizes just how challenging — and dangerous — it can really be.

Scanlon told me about a five-day backpacking trip he took to the majestic Banff National Park. There was a man-made bridge over every creek crossing, except for one. The trail directed Scanlon and his friends to cross a wide, swift, deep river, and despite scouting other options, they found there was no good spot to cross elsewhere.

At first, Scanlon felt safe, knowing how to cross a river, including facing upstream

Scenes from James Murren’s story, “How to plan a bikepacking trip across Catalina.”

(James Murren / For The Times)

, leaning into the oncoming water flow and shuffling slowly, moving through stable sidesteps.

But as he entered the outside curve, which he knew would be the fastest and deepest part, he was in water almost to his hips, “which is the no-go zone.”

“But I was almost there, and I got pretty close to getting toppled over, but I leaned into the oncoming water extra hard to counterbalance it and somehow got through,” he said. “Even when you do it right, you can still have issues, but I think the majority of times it’s not knowing the technique, not knowing where it’s best to cross and maybe the hubris factor.”

4. Falling from high places

People are increasingly getting too bold in high places, especially in the name of selfies and social media posts, Scanlon said.

The way to get ahead of this problem on your own journey is to decide yourself and within your group that you will not let the glory ahead of you influence your behavior.

I did similar on a recent trip to Taft Point, where multiple travelers have fallen to their deaths. I’d seen the gorgeous images of hikers sitting or posing on a rock that juts out dramatically over Yosemite Valley, and I’d told myself, “Maybe not.” Instead, my dear friend Patrick captured my image safely from a lookout point (which, per optical illusion, looks like I’m much closer to the edge than I am).

It can be hard to fight against this FOMO, but going beyond safety rails or going off-trail for better views or trying to impress our friends can all lead to deadly outcomes.

“There are certainly people who’ve fallen from unstable ground beneath them, and that you can’t necessarily prepare for,” Scanlon said. “But the majority of [accidents] are bad behaviors, like poorly executed selfies and [people] doing things they really shouldn’t. We should not be doing our first handstand ever on an 800-foot cliff.”

A trail sign at Vasquez Rocks Natural Area reminds guests of one of the most important tenants of hiking: Stay on the trail.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

5. Getting lost

This is arguably both the most important chapter (Skill 5: Land Navigation) of Scanlon’s book and the most important thing you can understand outside of hydrating appropriately.

Because, as Scanlon pointed out to me, understanding the factors around how we get lost “is extraordinarily important to nail down because getting lost is the gateway to the other perils.”

So, how do we not get lost?

In an estimated 40% of cases, a hiker got lost because they wondered off-trail, Scanlon wrote. This could be because they accidentally followed a spur or game trail, thinking it was the true trail. Another 17% of cases involve bad weather striking, and hikers moving off-trail to seek shelter.

Scanlon goes into extensive detail — just over 100 pages — about how to navigate in the wilderness, including how to use the different types of compasses, understanding the different parts of the compass and more.

One of his suggestions is easy enough to follow: “Before venturing out on any day hike or backpacking trip, study the map ahead of time and identify the nearest safety point,” whether that be a nearby road, railway, local airport or nearby town. Whatever you choose, it should hold the highest potential for seeing other people who can help and have the fewest visible obstacles on the map to arrive there.

“Navigating to this safety point will be our fallback plan when we have become lost and all else fails to get us back to the trail or trailhead,” Scanlon wrote.

I hope you can take this knowledge and apply it to your next hike. I know I will (and probably also pack Scanlon’s book in my backpack), along with carrying this mindset with me on the trail:

“The No. 1 goal is everyone gets home in one piece, and the secondary goal to get to the summit” or wherever you’re headed, Scanlon told me. “As long as you start out with the predetermined goal that everybody gets home, I think everything you prepare for and every on-trail decision you make should be serving that goal.”

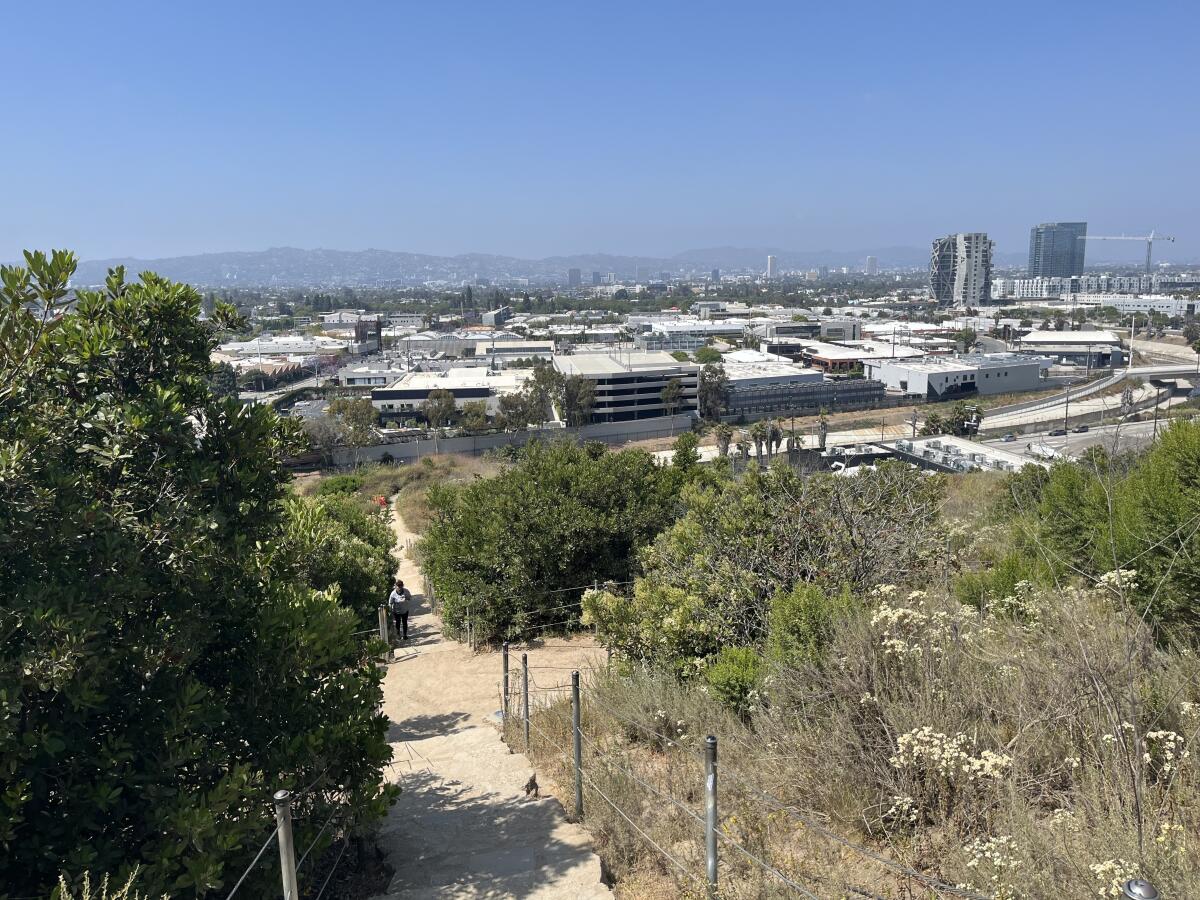

The views from the Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook include Culver City and the surrounding L.A. area.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

3 things to do

1. Roast marshmallows in the Baldwin Hills

The Nature Nexus Institute and California State Parks will host a campfire stroll from 1 to 3 p.m. Saturday at Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook. Families can participate in hands-on activities, listen at storytime and roast marshmallows for s’mores by the campfire. Register using the park’s Google form.

2. Heal the land in Elysian Park

Volunteers are needed in two shifts Friday at Elysian Park to help maintain native plant life. From 8 to 10 a.m., volunteers will work at the burn plot, an experimental restoration garden. Later in the day, volunteers will prune and water plants from 3:30 to 5:30 p.m. Learn more about the morning event at testplot.info and the afternoon event here.

3. Document flora and fauna in Pacoima

L.A. city’s junior urban ecologist Ryan Kinzel will host a community science-focused hike from 8 to 10 a.m. Saturday at Hansen Dam (10965 Dronfield Ave., Pacoima). Kinzel will lead guests in participating in the L.A. Nature Quest by using app iNaturalist to document plant and animal life as the group hikes. Learn more at the parks department’s Instagram page.

The must-read

Scenes from James Murren’s story, “How to plan a bikepacking trip across Catalina.”

(James Murren / For The Times)

There are so many ways to experience Catalina Island, including bikepacking. Times contributor James Murren took a two-day trip from East End to Little Harbor Campground and back to Avalon, covering 40-plus miles and about 5,000 feet of elevation. In his guide on how to bikepack the island, Murren writes about not only the beauty but also the surprising solitude he found there. “I had not seen another person for quite a while as I biked deeper into the hinterlands of the island, connecting to East End Light Road,” Murren wrote. “Along the ‘backside’ of the southern end of Catalina, it felt even more remote. East End afforded stunning views of the ocean and San Clemente Island to the south.” What a remarkable opportunity — and it’s only a ferry ride away!

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

Birders off the coast of Sonoma and Marin counties got quite the surprise last week when they spotted the critically endangered waved albatross, the largest bird in the Galapagos! It’s believed to be the first sighting of the bird north of Costa Rica, and it remains unclear what brought it more than 3,000 miles north of its homeland. Those lucky enough to see it included a seabird tour. “The excitement level on the boat when the bird was first identified was intense, with much screaming and shrieking, followed by beatific smiles from a dream come true,” passenger Glen Tepke told a Press Democrat reporter. Ah, the mystery and surprise that each new adventure brings!

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.