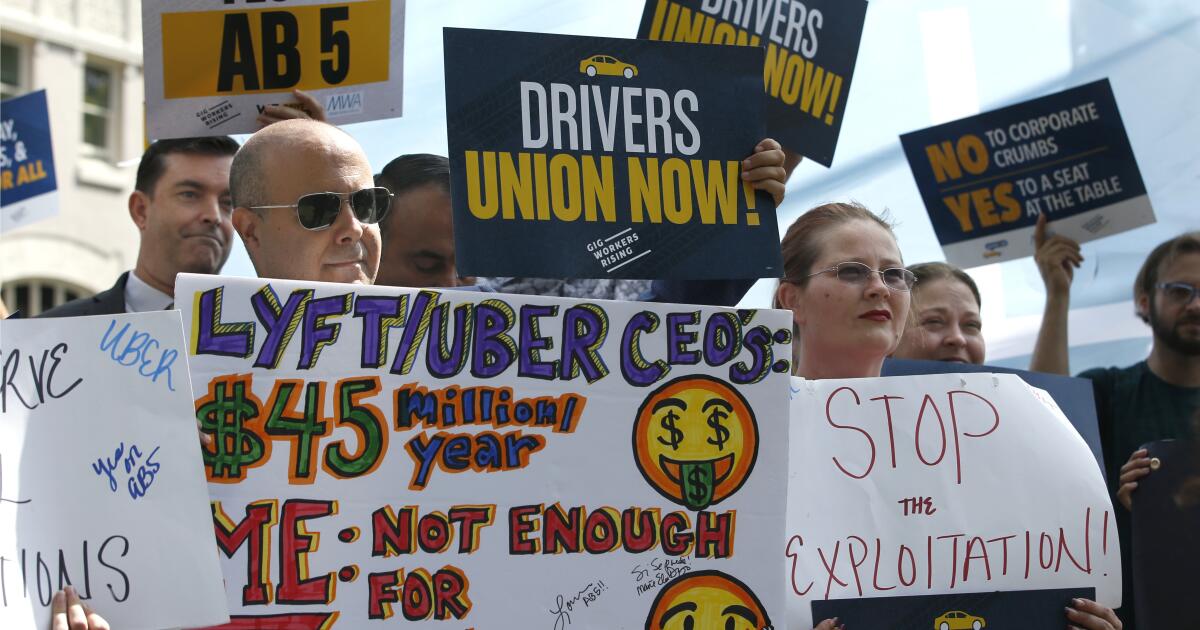

New law signed by Newsom allows ride-share drivers to unionize

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Friday signed into law a deal that will allow hundreds of thousands of rideshare drivers to unionize and bargain collectively while still being classified as independent contractors.

The legislation — a rare compromise between labor groups and Silicon Valley gig economy companies — grants collective bargaining rights to Uber and Lyft drivers, and follows years of political and legal battles over the job status of rideshare and delivery drivers.

The new law does not apply to other types of gig workers, including those who deliver food through apps like DoorDash.

Besides the collective bargaining deal, Newsom is also expected to sign a law backed by Uber and Lyft that would significantly reduce the companies’ insurance requirements.

Newsom, with his signing of the deal, drew a contrast with Trump’s posture towards workers and labor unions, with his administration banning collective bargaining at half a dozen federal agencies earlier this year.

“Donald Trump is holding the government hostage and stripping away worker protections. In California, we’re doing the opposite: proving government can deliver,” Newsom said in a statement. “That’s the difference between chaos and competence.”

Labor leaders from Service Employees International Union California, a powerful union that has been working for years to organize app-based drivers, say the deal is one of the largest expansions of private sector unions in 90 years, allowing hundreds of thousands of California gig drivers to gain a seat at the bargaining table.

It does so by exempting workers from the state and federal antitrust laws that normally prohibit collective action by independent contractors.

“The gig economy isn’t going away, but worker exploitation doesn’t have to be part of it.” David Green, SEIU 721 President and Executive Director.

Ramona Prieto, Uber’s Head of Public Policy for California, said in an emailed statement that the compromise “lowers costs for riders while creating stronger voices for drivers — demonstrating how industry, labor, and lawmakers can work together to deliver real solutions.”

Experts say the prospect of a union gives some gig workers their first-ever outlet to vent frustrations about workplace conditions. But how exactly does it work? And what are rideshare companies getting in return?

Here’s what you need to know:

What would it take for drivers to form a union?

Under federal law, employees in the U.S. can unionize by holding an election or reaching a voluntary agreement with their employers for a specific union to represent them.

The process for California Uber and Lyft drivers under the collective bargaining law, called Assembly Bill 1340, would be somewhat different.

A group can seek to be the bargaining representative for active drivers by collecting signatures from at least 10% of them. At that point, a group would be able to petition for access to names and contact information for all active drivers in California from the state’s Public Employment Relations Board, which is designated to oversee the unionization process.

With that contact list, the process of organizing drivers would in theory become easier. Once a group signs up 30% of active drivers, they could petition the board for union certification. If more than one organization is in the process of gathering signatures, an election would be held to determine which would represent drivers.

Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland), who co-authored the bill with Marc Berman (D-Menlo Park), said the new process means drivers will be able to”bargain for better pay and protections, and help build a future where the gig economy works for the people behind the wheel.”

The law outlines a formula as to which drivers qualify as “active” based on a median number of rides they completed during the prior six month period, which determines who would be eligible to vote in the election.

It’s unclear at this point how many active drivers California has, as the number fluctuates, and rideshare companies do not release the information. Uber and Lyft will be required to submit data on active drivers to the state labor board on a regular basis under the new law.

That path to collective bargaining mirrors a ballot initiative approved by Massachusetts voters last fall that was also backed by SEIU, which allows drivers to form a union after collecting signatures from at least 25% of active drivers in the state.

Drivers affiliated with SEIU who supported the California bill said they spend long hours on the road, as many as 10 to 12 a day, but are not given the same protections as other workers. They say the law gives them an opportunity to negotiate their pay and other terms of their agreements with the companies.

“Drivers have had no way to fight back against the gig companies taking more and more of the passenger fare, or to challenge unfair deactivations that cost us our livelihoods,” said Ana Barragan, a gig driver from Los Angeles in a statement. “We’ve worked long hours, faced disrespect, and had no voice, just silence on the other end of the app.”

Some driver advocates have worried the law may not be strong enough to ensure that drivers can reach a fair contract.

Veena Dubal, a law professor at UC Irvine who studies the effect of technology on workers, had said the legislation does not clarify whether drivers would be protected if they collectively protested or went on strike, and doesn’t require that the companies provide data about wages.

“These are the crux of what makes a union strong and the very, very bottom line of what members need and want,” Dubal said. “That they couldn’t achieve those things — that’s a win for Uber.”

Michael Reich, a professor of economics and co-chair of the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at UC Berkeley who has closely studied the gig economy and advised on driver-related legislation, called a potential driver union “a golden opportunity” and the pair of laws “a good deal for both sides.”

What did gig economy companies get out of the deal?

The insurance bill, backed by Uber and Lyft and introduced by state Sen. Christopher Cabaldon (D-Yolo), would reduce the amount of insurance that companies like Uber and Lyft are required to provide for rides.

Uber said in a blog posted to its website, that the law helps to address “one of the biggest hidden costs impacting rideshare passengers and drivers in California.”

Currently, the companies must carry $1 million in coverage per rideshare driver for accidents caused by other drivers who are uninsured or underinsured. The companies have argued that current insurance requirements are so high that they encourage litigation for insurance payouts and create higher costs for passengers.

But beginning next year, passenger trips will instead be covered by $60,000 in uninsured motorist coverage per rideshare driver and $300,000 per accident.

Uber said it will maintain $1 million in liability insurance to cover injuries or property damage in accidents caused by their rideshare drivers, as well as insurance that covers the cost to repair the driver’s car, regardless of who is at fault for the damage.

The companies are also required to maintain $1 million in occupational accident coverage under gig economy law Proposition 22, which is supposed to help drivers with medical bills if they’re injured while driving, no matter who is at fault, Uber said.

What led to this point and how does Prop. 22 factor in?

After the California Legislature in 2019 rewrote employment law in 2019, clarifying and limiting when businesses can classify workers as independent contractors, Uber and Lyft went to the ballot in California, bankrolling an initiative to exempt their drivers.

When California voters passed Proposition 22, the ballot measure the companies funded in 2020, drivers were classified as independent contractors who, under federal law, do not have the right to organize. Proposition 22 had language that explicitly barred drivers from collectively bargaining over their compensation, benefits and working conditions.

But SEIU California argued that court decisions over Prop. 22 left an opening for the state Legislature to create a process for drivers to unionize, setting the state for lawmakers to introduce the collective bargaining bill. Uber and Lyft initially opposed the bill, until a deal was hammered out and announced in August.

Times staff writer Laura Nelson contributed to this report.