How Trump’s cuts to weather experts could imperil California

WASHINGTON — When a fire erupts in California, it is a lab across the country, at the University of Maryland, that works together with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to determine where the smoke is going. Those unsung scientists help warn the people downwind of dangerous air quality levels.

About a half-hour drive away, NOAA’s Satellite Operations Facility provides the bulk of the work used to forecast atmospheric rivers that are crucial — and sometimes threatening — to communities across the state.

And it is the National Weather Service, working with buoys at sea and satellites in orbit, figuring out the risks of increased winds and dryness that could prompt devastating fires in highly populated areas such as Los Angeles.

It is not just meteorologists and technicians being forced out of their jobs en masse, jeopardizing the standards of those programs, said Craig McLean, a 40-year veteran of NOAA who served as the agency’s assistant administrator for research and acting chief scientist until his retirement in 2022.

The Trump administration proposes to go further, seeking to eliminate the entire research team that provides forecasters with tools to make their assessments. The Satellite Operations Facility has been hit with deep layoffs. Contracts for the buoys, and other equipment, are on hold while under review by the Commerce Department.

It is a cascade of delays and setbacks that could become evident to the public sooner rather than later, McLean said.

“The forecast risk is apparent upon us,” he told The Times. “I think it’s ridiculous to assume that it’s not — whether it’s for the fire season and the hydrology, whether it’s for the atmospheric rivers and the inundation and deluge, or whether it’s just for the high wind.”

Newsletter

You’re reading the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

George Skelton and Michael Wilner cover the insights, legislation, players and politics you need to know in 2024. In your inbox Monday and Thursday mornings.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Trump seeks cuts both to forecast and response

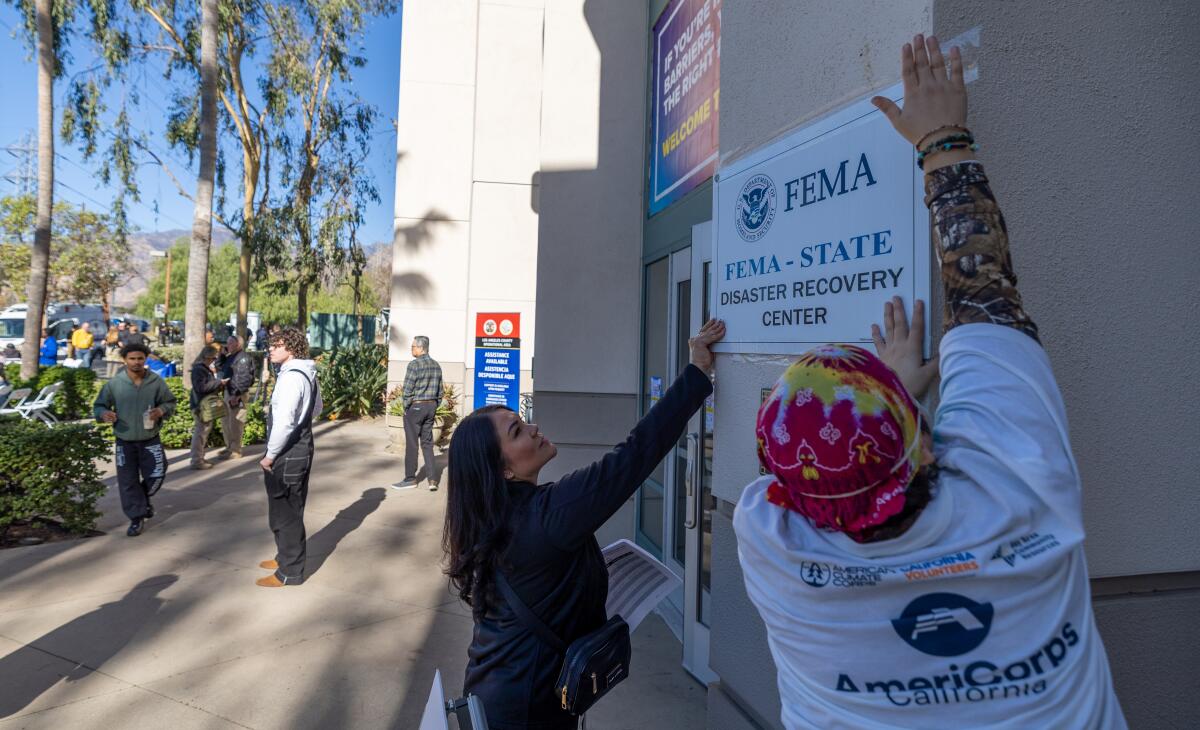

Workers put up a sign as wildfire victims seek disaster relief services at a FEMA center in Pasadena in January.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

The Trump administration’s cuts to NOAA, which have resulted in roughly 600 employee departures, or an about 15% of its workforce, appear to involve across the entire agency, based on self-reporting from employees and the National Weather Service Employees Organization. But the agency itself has provided few details to the public on the extent of its reductions.

“When the voluntary early retirement separation initiative was put up, in one day, NOAA lost 27,000 person years of experience, which is extraordinary in an agency of what was 12,000 personnel,” said Rick Spinrad, who served as administrator of the agency under President Biden.

“So much of what is done at NOAA is interpretive,” he added. “At the end of the day, when your weather forecast office or your local sea grant extension agent is informing you of what might happen, there’s a lot of interpretation of the environment, of local geography, local roads. That experience is gone.”

But if NOAA and the National Weather Service are ill-prepared for hazardous weather events — entering fire season in the West and hurricane season in the East — the Federal Emergency Management Agency may be worse off, having lost nearly a third of its employees since January. This week, Reuters reported that President Trump’s acting FEMA chief, David Richardson, told staff that he wasn’t aware the country had a hurricane season.

Trump has already raised concerns that he is rejecting disaster relief to states for political reasons. In the first three months of his presidency, Trump issued conditions on disaster aid to California after fires ravaged Los Angeles and rejected requests for disaster relief from Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and North Carolina Gov. Josh Stein, both Democrats.

Californians may find themselves more vulnerable to other natural disasters, as well. FEMA announced this month it would cancel $33 million in grants for Californians to retrofit their homes to gird against earthquakes, sparking “grave concern” among state officials. “This move must be reversed before tragedy strikes next,” Democratic Sen. Adam Schiff of California wrote to the agency.

More disruption for ports and fisheries

Each year, before fishing season begins, NOAA issues a series of scientific reports surveying fish populations and environmental conditions, a basic precaution to prevent permanent damage and overfishing along America’s coasts.

But this spring, staff cuts to NOAA forced the agency to take emergency action on the East Coast so that fishing could begin by May 1. And in Alaska, it took the state’s two Republican senators to plead with the White House to take action to allow fishing to resume.

“The federal government has to do two things: They need to do robust surveys for accurate stock assessments and timely regulations to open fisheries. That is it. When the federal government does not do that, you screw hardworking fishermen,” GOP Sen. Dan Sullivan of Alaska said at a hearing in May. “To be honest, right now, it is not looking good, and I am getting really upset.”

Their challenges don’t stop there. Fishing ships will not able to sail on time without reliable forecasts from the National Weather Service, likely resulting in a reduction of the number of days out at sea and, in turn, leading to fewer profits and staff members.

Americans are already being told to expect higher seafood prices, due to Trump’s tariff policies driving up duties on seafood imports by 10% to 30%, according to a new United Nations report.

“A fisherman who goes out to collect their lobster pots or go fish for tuna needs a reliable weather report,” said Mark Spalding, president of the Ocean Foundation. “Everybody who works with NOAA, from fishermen to shipping, to other businesses that rely on weather and the predictability of currents and storms, are going to feel less secure if not operating blind.”

Similar problems are facing the country’s largest ports, which rely on government experts in ocean monitoring that have left their jobs.

“At the ports of Long Beach and L.A., the systems used to optimize the ships coming in and out of the ports — the coastal ocean observing systems — are being compromised,” Spinrad said. “The president’s budget threatens to eliminate a lot of that capability.”

Vulnerabilities across the Pacific

In Singapore over the weekend, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth warned that a Chinese assault on Taiwan “could be imminent” and would threaten the entire Pacific region, including the United States. He touted U.S. partnerships across the region on maritime security — an acknowledgment that any conflict that might arise in the Pacific would be a fight at sea.

Cuts to NOAA could threaten U.S. readiness, McLean said.

“Because we have territories throughout the Pacific, NOAA is responsible for providing weather forecasts in those areas,” he said. “The defense community doesn’t operate completely dependent on NOAA in military conflicts — they have meteorologists in the Air Force and the Navy. But they are using NOAA models and are heavily guided by what the NOAA forecasts are offering, certainly for bases, whether it’s in Guam or Hawaii.”

The military, for example, uses data produced by thousands of buoys deployed and tracked by NOAA — called the Argo Float Network — that are considered the gold standard in ocean monitoring. The program faces cuts from the Trump administration because of its affiliation with climate change.

“There is a national defense component here,” McLean said. “The defense community is dependent upon what NOAA provides, both in models and in research.”

What else you should be reading

The must-read: California FEMA earthquake retrofit grants canceled, imperiling critical work, Schiff says

The deep dive: ‘Another broken promise’: California environmental groups reel from EPA grant cancellations

The L.A. Times Special: ‘It’s a huge loss’: Trump administration dismisses scientists preparing climate report

More to come,

Michael Wilner

—

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox.