Borno’s Resettled Families Are Quietly Fleeing Again

After over a decade of displacement, 63-year-old Fanne Goni believed life was finally returning to normalcy for her, her husband, and their seven children. It was 2019, and the Borno State government had announced the resettlement of displaced families to Kawuri, their hometown in northeastern Nigeria.

During those long years away, Fanne and her family stayed in a relative’s house in Maiduguri, the state capital. It had been offered to them after they fled their village. However, the living conditions were deplorable.

The town looked familiar and strange when the government eventually conveyed Fanne’s family and other households to Kawuri. Streets once alive with children’s laughter, cultural monuments, and sacred groves were now overgrown with weeds. Their crumbled mud homes were replaced with newly constructed housing units, uniform in shape and pale in colour.

For Fanne, stepping into her new home brought relief and a hope that the long years of suffering were finally behind them.

But it wasn’t. Not even close.

Every essential supply they had brought was gone a few months after their return.

“We are left with nothing,” Fanne said.

The harsh reality soon set in. They needed to rebuild their means of livelihood, but the persistent presence and growing threat of Boko Haram insurgents made that nearly impossible.

“We lack access to clean water and functional schools. Our children aren’t attending school, and the little we gather from the bush is taken from us at night,” she told HumAngle. “There are structures now. But no teachers because of the insecurity. Even those among us who are qualified to teach can’t do so. The schools are there, but they don’t function.”

What was meant to be a fresh start slowly began to feel like another form of displacement, this time, without leaving home.

Healthcare offered no comfort either. Fanne recalled falling seriously ill and being taken to the local clinic. “There were no drugs, no doctor to treat me. They had to refer me to the University Teaching Hospital in Maiduguri,” she recounted.

Then came a more personal blow. Her 18-year-old daughter, Kaltum Batuja, married a man who used to be a Boko Haram insurgent. Without telling anyone, Kaltum followed her husband to Sambisa Forest to live with the terror group.

“They married without our knowledge,” Fanne said. “Now I have two children with Boko Haram and the rest with me.” The other children had been abducted by the insurgents years earlier.

Although eloping may not be unusual in Kawuri’s folklore, a young girl running away with a terrorist deserter was seen as an abominable act that left the entire community in shock.

By November 2024, life in Kawuri had become unbearable. Insecurity, hunger, and the constant threat of Boko Haram attacks made living an everyday life impossible. Quietly, families began fleeing—one after the other. Fanne’s family slipped away at night in December, resettling again in Dalori, a village near Maiduguri.

We returned to Kawuri, but nothing worked. We were forced to leave again,” she said.

Once again displaced, Fanne now tries to piece her life together, just as she had tried to do in Kawuri. She now supports herself by processing and selling groundnuts. With ₦3,000 a month, she rents two small rooms in Dalori’s 1000 Housing Unit.

A fragile settlement

Unlike many other towns and villages in Borno State, Kawuri, a roadside town, was displaced as early as 2014, at the height of Boko Haram’s violent rampage against local communities. Situated along the Konduga–Bama road, Kawuri was once a prominent and historic settlement in Konduga Local Government Area, a place its people proudly called home.

The residents were predominantly farmers and traders, while the community’s hunters were well known for their skilled game activities in the nearby Sambisa Forest, which has now become a stronghold for the insurgents. All of that changed when terror seized everything, forcing the entire population to flee and leaving behind only silence and ruins.

For over a decade, Kawuri’s displaced population lived in makeshift camps and host communities across Maiduguri, or crossed borders into neighbouring countries like Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, waiting for a chance to return home.

That opportunity came in 2019, when the Borno State government began an ambitious programme to repatriate displaced communities. Kawuri was among the first to be resettled. As part of the effort, 500 housing units and additional shelters were constructed to accommodate returnees who had spent years in exile.

Upon their return, residents began rebuilding their lives, turning to small-scale farming and firewood collection to survive. Despite security presence, locals told HumAngle the forces were limited in their capacity to defend the community, relying largely on rudimentary trenches.

Kawuri’s proximity to the Sambisa Forest soon turned fragile hope into renewed fear. The surrounding bushes became deadly terrain. Insurgents began abducting and killing people who ventured out to farm or fetch firewood.

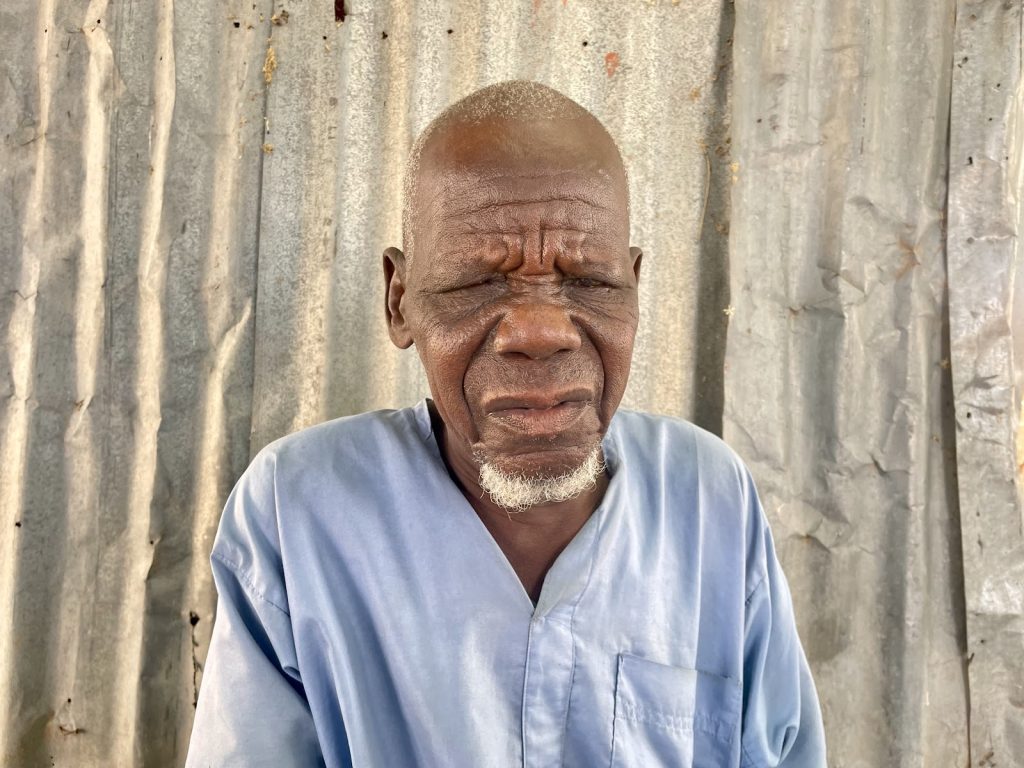

The son of Bunu Modu Jiddor, a 75-year-old retired civil servant, was one of the victims. “We paid a ransom to get him back,” he said. The abductors demanded a million naira as ransom at first, according to Bunu, but eventually they negotiated ₦250,000 for his release.

With time, Boko Haram insurgents carrying rifles started infiltrating the town more frequently. Locals told HumAngle that the insurgents would steal foodstuffs, clothes, buckets, and household items, often breaking into homes and looting at will, with no resistance from the terrified population.

Some Kawuri residents, desperate to survive, reluctantly agreed to run errands for the insurgents. In a region where venturing into the bush to fetch firewood is vital for daily living, complying with their demands often meant avoiding harassment or violent attacks.

“When our wives and children go to the bush to collect firewood or fetch water, Boko Haram stops them,” said Kadai Kawuri, a 72-year-old elder from Dubdori ward in Kawuri, who has been displaced twice in the past decade. “Sometimes, they demand something before allowing them to pass. Other times, they kidnap them, and we’re forced to gather what little we have to pay ransom.”

Cooperating with the insurgents, residents explained, was never out of loyalty; it was a desperate strategy to preserve a fragile semblance of peace and reduce the risk of becoming a target during routine activities.

But this uneasy relationship brought more trouble. Local sources said the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) and soldiers began arresting people suspected of delivering items like salt, seasoning cubes, or cassava to the insurgents. Anyone caught was taken to military barracks. Fearing arrest, many avoided such errands entirely.

While some arrests were justified, community members say they are also subject to harassment and false accusations. “Sometimes they just pick someone and say he’s working with Boko Haram, even when it’s not true,” said Kadai. “They have accused people unfairly, and it causes fear and division among us.”

These accusations have made it difficult for the community to rebuild trust and stability. Instead of feeling protected, some residents now feel watched and judged, adding another layer of anxiety to an already fragile resettlement experience.

The situation escalated further when security agencies began punishing and prosecuting those found guilty of trading with Boko Haram. According to Abbagana Mohammed, a resident, this provoked the insurgents into retaliating with violence. “They took violent action against men, women, and children of Kawuri,” he said.

In a chilling warning, over 200 armed Boko Haram members on motorbikes and vehicles stormed into Kawuri, and their message was simple: “If the community continued to refuse their errands, they would return to slaughter everyone, and burn the village down,” recalled a resident who declined to be named for fear of retaliation.

Caught between the wrath of Boko Haram and the suspicion and harassment of state security forces, Kawuri residents found themselves with no safe option. This unbearable pressure forced many to quietly flee again, abandoning the homes they had just begun to rebuild.

“There was nothing anyone could do. People left,” said Kadai. He fled his ancestral home to Dalori just four months before HumAngle met him.

Kawuri’s hope was sown, sprouted, and then withered, all within just four years of resettlement.

Could this be considered a failed return?

Renewed threats

Through investigations and field visits, HumAngle has been closely monitoring the conditions of resettled communities across Borno State, particularly those repatriated over the past couple of years.

Rather than returning to stability, many returnees have found themselves in even more difficult and insecure living conditions. Like Kawuri, these communities live under the constant threat of insurgent attacks and within tight military restrictions. Returnees report living in fear, with limited access to farmland and strict rules on what crops can be grown, often confined to shorter varieties like groundnuts, beans, and millet, making long-term food security nearly impossible.

In recent weeks, resettled communities across Borno have faced renewed threats from Boko Haram and its splinter faction, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). These insurgent groups have launched deadly attacks on several communities where residents had only just returned to their ancestral homes.

On April 17, for instance, militants stormed Yamtake in Gwoza Local Government Area, killing two soldiers and an unconfirmed number of civilians in a coordinated nighttime assault. A day earlier, suspected insurgents attacked Pulka, a community hosting thousands of resettled families, triggering heavy gunfire and sporadic shooting.

In Kirawa, a quiet border town near Cameroon, two local vigilantes were killed on Friday, April 25, while trying to repel a Boko Haram attack. The victims, Abba Aja and Abbaye Shettima, were members of the local hunters and vigilante group protecting the community. They died instantly during a confrontation with the insurgents around noon.

Locals in Kirawa blame the persistent insecurity in their community on the continued use of the Kirawa–Pulka road, which they say has become increasingly dangerous due to Boko Haram’s stronghold along a critical crossing point.

“There is a Boko Haram crossroad between two deserted towns, Manava and Sabon Gari,” Mohammed Amada, a councillor representing Kirawa Jimini Ward, told HumAngle. “They use it frequently to move between the mountainous terrain and the Sambisa Forest.”

Two years ago, HumAngle published a video documentary exposing the poor condition of this treacherous road and the grim realities faced by repatriated residents, just a year after their return to Kirawa.

The two vigilantes recently killed had been stationed at this strategic junction to help secure safe passage for military-escorted convoys.

“Our main challenge is the lack of active and effective security operations. We are calling on the government to strengthen the military base here,” Amada lamented. “Most of the security work, like escorts and patrols, is left to the vigilantes and Civilian Joint Task Force members.”

They often work without enough weapons, pay, or support. Some have even quit because they haven’t been paid for months.

According to Amada, the community has repeatedly appealed to the security forces, including the Multinational Joint Task Force, to increase their presence by conducting regular escorts for commuters and patrol operations along the dangerous road. However, he said, those requests have gone unanswered.

Kirawa was once a ghost town after Boko Haram attacked and seized it in 2014.

For almost a decade, its people lived in displacement camps across Nigeria or as refugees in Cameroon, waiting for the day they could return home.

That opportunity came in 2022, when the government began resettling communities. Kirawa was among them, and its people returned with hope to rebuild their homes, restart farming, and live in peace.

However, since their return, many families have faced hardship. Schools lack teachers and teaching materials. The health clinic is often closed because it lacks staff and amenities like electricity and medicine. Enough clean water is still hard to find, and residents usually walk back into Cameroon to access healthcare, buy medicine, or seek basic services.

When night falls, fear takes over. Boko Haram elements continue to infiltrate the town. People sleep with one eye open, and some even cross the border to sleep in Cameroon, only returning to Nigeria in the morning.

About 15,000 individuals from over 2,500 households were reported to have returned to Kirawa in 2022. However, within just two years, that population has declined drastically. According to the local councillor, the number of households remaining has dropped to around 1,500, as families continue to flee.

In February, the Borno State government led a delegation to repatriate over 7,000 Nigerian refugees from the Republic of Chad, where they had sought refuge for a decade after fleeing their communities in Nigeria. However, shortly after their cross-border return, many faced significant challenges, including inadequate security, food shortages, limited access to safe farmlands, and a lack of essential services such as healthcare and functional education. These hardships forced some to flee again, returning to Chad for the safety and stability they had left behind.

Coupled with continued attacks on resettled communities across Borno State, residents say it only reinforces their doubt in the government’s capacity to protect lives, provide basic services, and maintain stability.

There’s even a more brutal blow to this fragile trust. HumAngle’s investigation recently found issues relating to a lack of accountability from private and government bodies implementing projects and services in these resettled communities. These findings raise critical questions about the sustainability and safety of resettlement efforts in regions where the threat of violence is resurfacing across the Lake Chad region and targeting of repatriated communities is evident.

However, local authorities continue to resettle internally displaced families. Just last week, over 6000 residents of the Muna IDP camp in Maiduguri, one of the largest displaced persons settlements in the state, were set to be resettled to their ancestral homeland. While this marks a significant step in closing down the remaining IDP camps in the state capital, the experiences of residents in resettled communities like Kawuri and Kirawa raise disturbing concerns that the Muna resettlement may repeat past failures.