After Gavin Newsom was elected lieutenant governor, he repeatedly made clear his frustration with the job and its lack of responsibilities. The official portfolio for the office is thin, including sitting on boards that oversee the state’s higher education system and public lands, leading an economic council and serving as acting governor when California’s chief executive is out of state or otherwise unavailable.

Newsom, now the front-runner in the governor’s race, missed scores of meetings held by the University of California Board of Regents, the California State University Board of Trustees and the California State Lands Commission, according to a Times review of attendance records.

He attended 54% of UC Regents meeting days, 34% for Cal State and 57% for state lands, according to a Times review of attendance records between 2011 and 2018. The Times included in the tally days when Newsom was present for only part of the day, and excluded days when Newsom had no committee meetings or other official business to attend.

Membership of the three panels is the most prominent duty of a lieutenant governor, a post considered to be largely ceremonial.

“There’s no denying that the official responsibilities of the lieutenant governor are more modest than some other constitutional offices — the English call it an ‘heir and a spare,’” said former California Gov. Gray Davis, who was lieutenant governor before being elected to lead the state. “But 43 states have a lieutenant governor whose primary function is to step in if something happens to the governor.”

Newsom’s opponents have criticized him for failing to fully participate in the three panels, which set policy on tuition, athletics programs and expansion for much of the state’s higher-education system, and manage issues including oil drilling and access to some of California’s publicly owned lands.

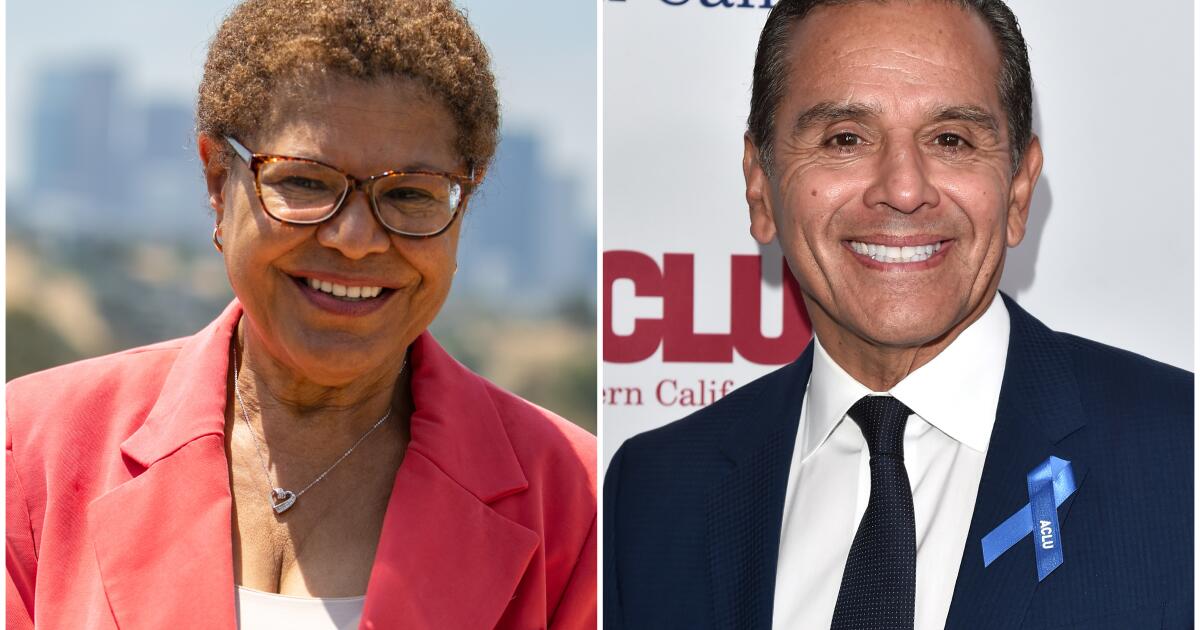

“Californians are working harder than ever before just to stay in the middle class. It appears Gavin Newsom is hardly working — or at least not working for the people who pay his salary,” said Luis Vizcaino, a spokesman for former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.

Newsom defended his record, saying it paralleled that of other elected officials on the panels.

“I’ve tried not to be the quote-unquote politician on the board. I tried to avoid being the guy who shows up just to give the press release. I tried to be constructive and I tried to be engaged,” he said in an interview. “Every tough vote, we were there — the ones that matter, the close votes.”

Observers of the UC and Cal State panels agreed that the elected officials on the boards had spottier attendance than appointees. The State Lands Commission comprises three members, so when one is absent, he or she typically sends an alternate to voice concerns and vote on the member’s behalf. Attendance on the panels has previously been raised as a campaign issue — Republican Dan Lungren poked Davis about his absences during a 1998 gubernatorial debate.

Newsom’s Democratic rivals in the race — state Treasurer John Chiang, former state schools chief Delaine Eastin and Villaraigosa — held various roles on the same three boards during prior terms in elected office. Chiang served on the State Lands Commission when he was controller, and Villaraigosa and Eastin sat on the UC and Cal State boards while serving as Assembly speaker and state superintendent of public instruction, respectively.

They also failed to attend many meetings.

Chiang attended 46% of Lands Commission meeting days between 2007 and 2014 when he was state controller. Villaraigosa and Eastin each attended less than 10% of the Cal State meetings during their time on that board. Though they both routinely skipped UC meetings, the full picture of their attendance is unclear due to a lack of available records documenting their time on the boards in the 1990s.

But their jobs at the time were more demanding than the role of lieutenant governor. The speaker must be in Sacramento during the legislative session, and the state schools chief oversees curriculum, testing and finances for the 6.3 million students in the state’s schools. As controller, Chiang was California’s chief bookkeeper, administering the state’s payroll and serving on more than 70 boards and commissions.

Newsom’s responsibilities as lieutenant governor are much more limited in scope, a point he has frequently drawn attention to.

Before he ran for lieutenant governor in 2010, he derided the role as having “no real authority and no real portfolio.”

After he was elected, he drafted legislation to put the office of lieutenant governor on the gubernatorial ticket — similar to how a president and vice president are elected together — but couldn’t find a legislator to carry the bill. If elected governor, Newsom said he hopes to revisit the proposal.

Two years into the job, during a break in filming his Current TV show, Newsom was asked by friend and hotelier Chip Conley how frequently he went to Sacramento.

“Like one day a week, tops,” Newsom said. “There’s no reason.… It’s just so dull.”

A few months later, as a Times reporter trailed Newsom in the Capitol, he stopped when a woman asked him to pose for a picture with her son. The boy asked him what a lieutenant governor does.

“I ask myself that every day,” Newsom replied.

He has repeatedly joked about the post over the years, including in an interview with The Times during his 2014 reelection campaign when he paraphrased a line from then-Secretary of State John F. Kerry, himself a former lieutenant governor: “Wake up every morning, pick up the paper, read the obituaries, and if the governor’s name doesn’t appear in there, go back to sleep.”

Garry South, a former advisor to Newsom who is not publicly backing a candidate in the governor’s race, recalled urging him to knock it off.

“I did convey to him on a couple of occasions … that I didn’t think it was a good idea to tell voters they had elected you to a worthless position,” South said. “To his credit, I think he’s done much less of that in the last few years.”

Newsom said that the transition from mayor of San Francisco — when he worked on issues including same-sex marriage, universal healthcare and homelessness — to lieutenant governor was difficult.

“In honesty, I totally get it. I’m not even going to be defensive about it. There was absolutely early frustration. That’s all it represented years and years ago,” he said, noting that his time in Sacramento has been much slower than his life as mayor, a change he described as a “major cultural transition.” “It’s a different pace. That was reflected in those lazy comments of mine [that] I by definition regret because we wouldn’t be having this conversation. But it expressed a sentiment at the time.”

Newsom said he grew into his job and realized he could use his bully pulpit to promote issues he cared about, including successful 2016 ballot measures to legalize recreational marijuana and implement stricter gun controls.

Still, Newsom’s statements about his job have provided plenty of fodder for his rivals.

“If he was so bored, why did he refuse to show up for his job on the UC Board of Regents, or on the CSU Board of Trustees or at the State Lands Commission? Where was Gavin when he was supposed to be working on behalf of all the Californians who actually show up for their jobs?” said Fabien Levy, a spokesman for Chiang. “California needs a serious leader, not someone who’s in it just for show.”

But parties with business before the panels and fellow members said Newsom has been active and attentive when present.

“He has been engaged and thoughtful, and particularly interested in the financial structures and financial stability and financial accountability,” said Shane White, chairman of UC’s Academic Senate and a dentistry professor at UCLA.

A fellow UC regent, who asked to remain anonymous to speak freely about Newsom’s tenure on the board, agreed.

“He’s been substantially more engaged than the vast majority of elected officials who have served on the board,” said the regent, who is unaligned in the race. “He does his homework.”

Former Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez, a Villaraigosa backer who sits on the UC Regents board, said Newsom’s attendance is not that different from other elected officials who sit on the panel.

“If you want to hit him for attendance, it’s a valid hit. If you want to hit him for only being involved in the most high-profile issues, it’s a valid hit. But it’s not inconsistent with other ex officio board members,” Pérez said, adding that he personally liked Newsom and the two men frequently voted on controversial issues the same way. “The difference is he made such a big deal about [how] the office doesn’t do anything, and then he doesn’t go to the things it does.”

Follow California politics by signing up for our email newsletter »

Coverage of California politics »

[email protected]

For the latest on national and California politics, follow @LATSeema on Twitter.