Is Mali about to fall to al-Qaeda affiliate JNIM? | Armed Groups News

A months-long siege on the Malian capital, Bamako, by the armed al-Qaeda affiliate group, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), has brought the city to breaking point, causing desperation among residents and, according to analysts, placing increasing pressure on the military government to negotiate with the group – something it has refused to do before now.

JNIM’s members have created an effective economic and fuel blockade by sealing off major highways used by tankers to transport fuel from neighbouring Senegal and the Ivory Coast to the landlocked Sahel country since September.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

While JNIM has long laid siege to towns in other parts of the country, this is the first time it has used the tactic on the capital city.

The scale of the blockade, and the immense effect it has had on the city, is a sign of JNIM’s growing hold over Mali and a step towards the group’s stated aim of government change in Mali, Beverly Ochieng, Sahel analyst with intelligence firm Control Risks, told Al Jazeera.

For weeks, most of Bamako’s residents have been unable to buy any fuel for cars or motorcycles as supplies have dried up, bringing the normally bustling capital to a standstill. Many have had to wait in long fuel queues. Last week, the United States and the United Kingdom both advised their citizens to leave Mali and evacuated non-essential diplomatic staff.

Other Western nations have also advised their citizens to leave the country. Schools across Mali have closed and will remain shut until November 9 as staff struggle to commute. Power cuts have intensified.

Here’s what we know about the armed group responsible and why it appears to have Mali in a chokehold:

What is JNIM?

JNIM is the Sahel affiliate of al-Qaeda and the most active armed group in the region, according to conflict monitor ACLED. The group was formed in 2017 as a merger between groups that were formerly active against French and Malian forces that were first deployed during an armed rebellion in northern Mali in 2012. They include Algeria-based al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM) and three Malian armed groups – Ansar Dine, Al-Murabitun and Katiba Macina.

JNIM’s main aim is to capture and control territory and to expel Western influences in its region of control. Some analysts suggest that JNIM may be seeking to control major capitals and, ultimately, to govern the country as a whole.

It is unclear how many fighters the group has. The Washington Post has reported estimates of about 6,000, citing regional and western officials.

However, Ulf Laessing, Sahel analyst at the German think tank, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS), said JNIM most likely does not yet have the military capacity to capture large, urban territories that are well protected by soldiers. He also said the group would struggle to appeal to urban populations who may not hold the same grievances against the government as some rural communities.

While JNIM’s primary base is Mali, KAS revealed in a report that the group has Algerian roots via its members of the Algeria-based al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM).

The group is led by Iyad Ag-Ghali, a Malian and ethnic Tuareg from Mali’s northern Kidal region who founded Ansar Dine in 2012. That group’s stated aim was to impose its interpretation of Islamic law across Mali.

Ghali had previously led Tuareg uprisings against the Malian government, which is traditionally dominated by the majority Bambara ethnic group, in the early 1990s, demanding the creation of a sovereign country called Azawad.

However, he reformed his image by acting as a negotiator between the government and the rebels. In 2008, he was posted as a Malian diplomat to Saudi Arabia under the government of Malian President Amadou Toumani Toure. When another rebellion began in 2012, however, Ghali sought a leadership role with the rebels but was rebuffed, leading him to create Ansar Dine.

According to the US Department of National Intelligence (DNI), Ghali has stated that JNIM’s strategy is to expand its presence across West Africa and to put down government forces and rival armed groups, such as the Mali-based Islamic State Sahel, through guerrilla-style attacks and the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Simultaneously, it attempts to engage with local communities by providing them with material resources. Strict dress codes and bans on music are common in JNIM-controlled areas.

JNIM also destroys infrastructure, such as schools, communication towers and bridges, to weaken the government off the battlefield.

An overall death toll is unclear, but the group has killed thousands of people since 2017. Human rights groups accuse it of attacking civilians, especially people perceived to be assisting government forces. JNIM activity in Mali caused 207 deaths between January and April this year, according to ACLED data.

How has JNIM laid siege to Bamako?

JNIM began blocking oil tankers carrying fuel to Bamako in September.

That came after the military government in Bamako banned small-scale fuel sales in all rural areas – except at official service stations – from July 1. Usually, in these areas, traders can buy fuel in jerry cans, which they often resell later.

The move to ban this was aimed at crippling JNIM’s operations in its areas of control by limiting its supply lines and, thus, its ability to move around.

At the few places where fuel is still available in Bamako, prices soared last week by more than 400 percent, from $25 to $130 per litre ($6.25-$32.50 per gallon). Prices of transportation, food and other commodities have risen due to the crisis, and power cuts have been frequent.

Some car owners have simply abandoned their vehicles in front of petrol stations, with the military government threatening on Wednesday to impound them to ease traffic and reduce security risks.

A convoy of 300 fuel tankers reached Bamako on October 7, and another one with “dozens” of vehicles arrived on October 30, according to a government statement. Other attempts to truck in more fuel have met obstacles, however, as JNIM members ambush military-escorted convoys on highways and shoot at or kidnap soldiers and civilians.

Even as supplies in Bamako dry up, there are reports of JNIM setting fire to about 200 fuel tankers in southern and western Mali. Videos circulating on Malian social media channels show rows of oil tankers burning on a highway.

What is JNIM trying to achieve with this blockade?

Laessing of KAS said the group is probably hoping to leverage discontent with the government in the already troubled West African nation to put pressure on the military government to negotiate a power-sharing deal of sorts.

“They want to basically make people as angry as possible,” he said. “They could [be trying] to provoke protests which could bring down the current government and bring in a new one that’s more favourable towards them.”

Ochieng of Control Risks noted that, in its recent statements, JNIM has explicitly called for government change. While the previous civilian government of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (2013-2020) had negotiated with JNIM, the present government of Colonel Assimi Goita will likely keep up its military response, Ochieng said.

Frustration at the situation is growing in Bamako, with residents calling for the government to act.

Speaking to Al Jazeera, driver Omar Sidibe said the military leaders ought to find out the reasons for the shortage and act on them. “It’s up to the government to play a full role and take action [and] uncover the real reason for this shortage.”

Which parts of Mali is the JNIM active in?

In Mali, the group operates in rural areas of northern, central and western Mali, where there is a reduced government presence and high discontent with the authorities among local communities.

In the areas it controls, JNIM presents itself as an alternative to the government, which it calls “puppets of the West”, in order to recruit fighters from several ethnic minorities which have long held grievances over their perceived marginalisation by the government, including the Tuareg, Arab, Fulani, and Songhai groups. Researchers note the group also has some members from the majority Bambara group.

In central Mali, the group seized Lere town last November and captured the town of Farabougou in August this year. Both are small towns, but Farabougou is close to Wagadou Forest, a known hiding place of JNIM.

JNIM’s hold on major towns is weaker because of the stronger government presence in larger areas. It therefore more commonly blockades major towns or cities by destroying roads and bridges leading to them. Currently, the western cities of Nioro and gold-rich Kayes are cut off. The group is also besieging the major cities of Timbuktu and Gao, as well as Menaka and Boni towns, located in the north and northeast.

How is JNIM funded?

For revenue, the group oversees artisanal gold mines, forcefully taxes community members, smuggles weapons and kidnaps foreigners for ransom, according to the US DNI. Kayes region, whose capital, Kayes, is under siege, is a major gold hub, accounting for 80 percent of Mali’s gold production, according to conflict monitoring group Critical Threats.

The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (Gi-Toc) also reports cattle rustling schemes, estimating that JNIM made 91,400 euros ($104,000) in livestock sales of cattle between 2017 and 2019. Cattle looted in Mali are sold cheaply in communities on the border with Ghana and the Ivory Coast, through a complex chain of intermediaries.

In which other countries is JNIM active?

JNIM expanded into Burkina Faso in 2017 by linking up with Burkina-Faso-based armed group Ansarul-Islam, which pledged allegiance to the Malian group. Ansarul-Islam was formed in 2016 by Ibrahim Dicko, who had close ties with Amadou Koufa, JNIM’s deputy head since 2017.

In Burkina Faso, JNIM uses similar tactics of recruiting from marginalised ethnic groups. The country has rapidly become a JNIM hotspot, with the group operating – or holding territory – in 11 of 13 Burkina Faso regions outside of capital Ouagadougou. There were 512 reported casualties as a result of JNIM violence in the country between January and April this year. It is not known how many have died as a result of violence by the armed group in total.

Since 2022, JNIM has laid siege to the major northern Burkinabe city of Djibo, with authorities forced to airlift in supplies. In a notable attack in May 2025, JNIM fighters overran a military base in the town, killing approximately 200 soldiers. It killed a further 60 in Solle, about 48km (30 miles) west of Djibo.

In October 2025, the group temporarily took control of Sabce town, also located in the north of Burkina Faso, killing 11 police officers in the process, according to the International Crisis Group.

In a September report, Human Rights Watch said JNIM and a second armed group – Islamic State Sahel, which is linked to ISIL (ISIS) – massacred civilians in Burkina Faso between May and September, including a civilian convoy trying to transport humanitarian aid into the besieged northern town of Gorom Gorom.

Meanwhile, JNIM is also moving southwards, towards other West African nations with access to the sea. It launched an offensive on Kafolo town, in northern Ivory Coast, in 2020.

JNIM members embedded in national parks on the border regions with Burkina Faso have been launching sporadic attacks in northern Togo and the Benin Republic since 2022.

In October this year, it recorded its first attack on the Benin-Nigeria border, where one Nigerian policeman was killed. The area is not well-policed because the two countries have no established military cooperation, analyst Ochieng said.

“This area is also quite a commercially viable region; there are mining and other developments taking place there … it is likely to be one that [JNIM] will try to establish a foothold,” she added.

Why are countries struggling to fend off JNIM?

When Mali leader General Assimi Goita led soldiers to seize power in a 2020 coup, military leaders promised to defeat the armed group, as well as a host of others that had been on the rise in the country. Military leaders subsequently seizing power from civilian governments in Burkina Faso (2022) and in Niger (2023) have made the same promises.

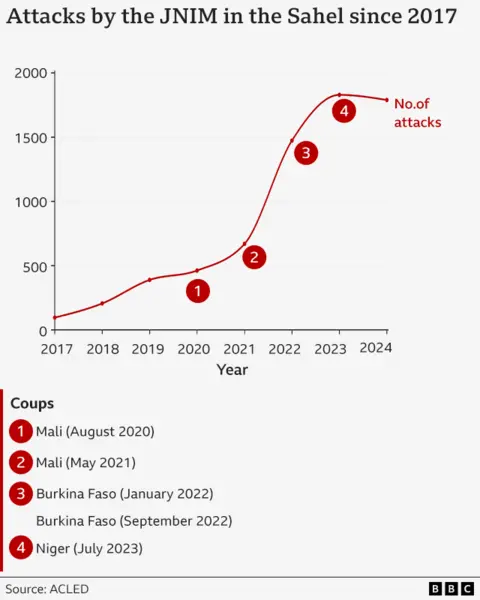

However, Mali and its neighbours have struggled to hold JNIM at bay, with ACLED data noting the number of JNIM attacks increasing notably since 2020.

In 2022, Mali’s military government ended cooperation with 4,000-strong French forces deployed in 2013 to battle armed groups which had emerged at the time, as well as separatist Tuaregs in the north. The last group of French forces exited the country in August 2022.

Mali also terminated contracts with a 10,000-man UN peacekeeping force stationed in the country in 2023.

Bamako is now working with Russian fighters – initially 1,500 from the Wagner Mercenary Group, but since June, from the Kremlin-controlled Africa Corps – estimated to be about 1,000 in number.

Russian officials are, to a lesser extent, also present in Burkina Faso and Niger, which have formed the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) with Mali.

Results in Mali have been mixed. Wagner supported the Malian military in seizing swaths of land in the northern Kidal region from Tuareg rebels.

But the Russians also suffered ambushes. In July 2024, a contingent of Wagner and Malian troops was ambushed by rebels in Tinzaouaten, close to the Algerian border. Between 20 and 80 Russians and 25 to 40 Malians were killed, according to varying reports. Researchers noted it was Wagner’s worst defeat since it had deployed to West Africa.

In all, Wagner did not record much success in targeting armed groups like JNIM, analyst Laessing told Al Jazeera.

Alongside Malian forces, the Russians have also been accused by rights groups of committing gross human rights violations against rural communities in northern Mali perceived to be supportive of armed groups.

Could the Russian Africa Corps fighters end the siege on Bamako?

Laessing said the fuel crisis is pressuring Mali to divert military resources and personnel to protect fuel tankers, keeping them from consolidating territory won back from armed groups and further endangering the country.

He added that the crisis will be a test for Russian Africa Corp fighters, who have not proven as ready as Wagner fighters to take battle risks. A video circulating on Russian social media purports to show Africa Corps members providing air support to fuel tanker convoys. It has not been verified by Al Jazeera.

“If they can come in and allow the fuel to flow into Bamako, then the Russians will be seen as heroes,” Laessing said – at least by locals.

Laessing added that the governments of Mali and Burkina Faso, in the medium to long term, might eventually have to negotiate with JNIM to find a way to end the crisis.

While Goita’s government has not attempted to hold talks with the group in the past, in early October, it greenlit talks led by local leaders, according to conflict monitoring group Critical Threats – although it is unclear exactly how the government gave its approval.

Agreements between the group and local leaders have reportedly already been signed in several towns across Segou, Mopti and Timbuktu regions, in which the group agrees to end its siege in return for the communities agreeing to JNIM rules, taxes, and noncooperation with the military.