I sank into Randy Carter’s comfy couch, excited to see the Hollywood veteran’s magnum opus.

Around the first floor of his Glendale home were framed photos and posters of films the 77-year-old had worked on during his career. “Apocalypse Now.” “The Godfather II.” “The Conversation.”

What we were about to watch was nowhere near the caliber of those classics — and Carter didn’t care.

Footage of a school bus driving through dusty farmland began to play. The title of the nine-minute sizzle reel Carter produced in 1991 soon flashed: “Boy Wonders.”

The plot: White teenage boys in the 1960s gave up a summer of surfing to heed the federal government’s call. Their assignment: Pick crops in the California desert, replacing Mexican farmworkers.

“That’s the stupidest, dumbest, most harebrained scheme I’ve heard in my life,” a farmer complained to a government official in one scene, a sentiment studio executives echoed as they rejected Carter’s project as too far-fetched.

But it wasn’t: “Boy Wonders” was based on Carter’s life.

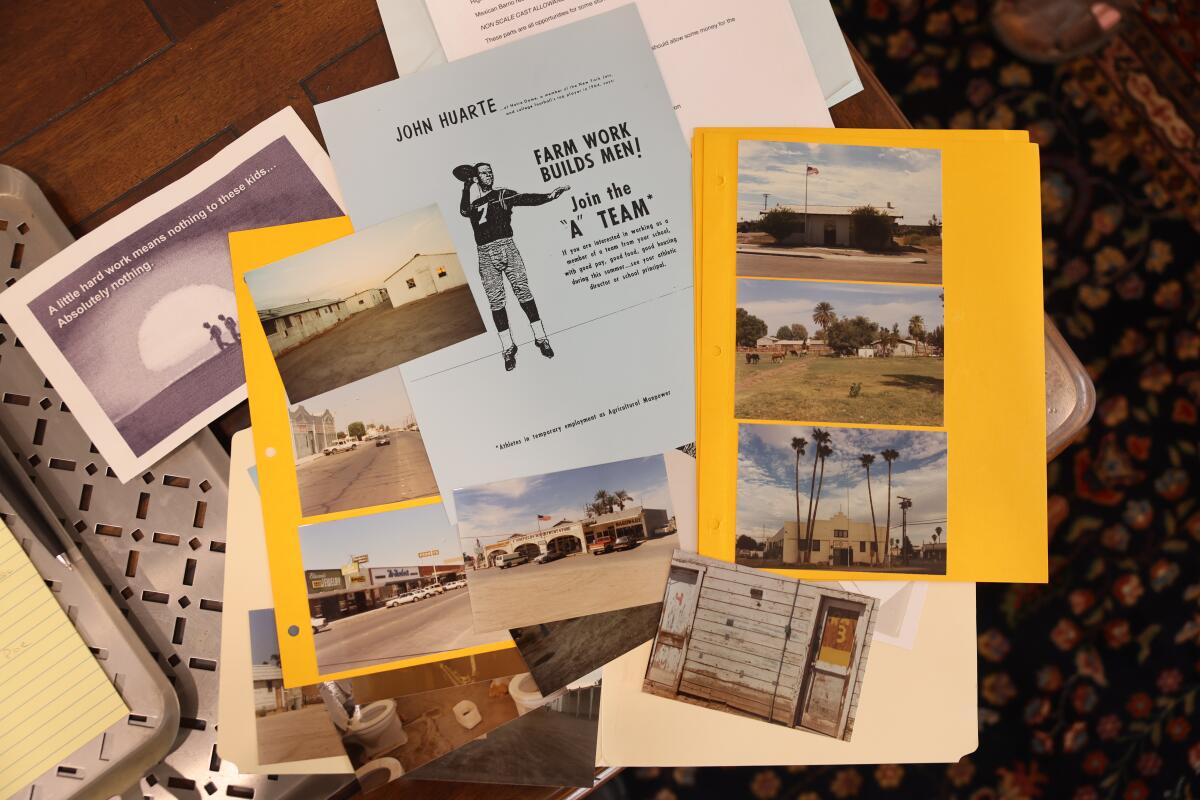

Randy Carter’s collection of historical photos and other memorabilia of A-TEAM, a 1965 program that sought to recruit high school athletes to pick crops during the summer.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

In 1965, the U.S. Department of Labor launched A-TEAM — Athletes in Temporary Employment as Agricultural Manpower — with the goal of recruiting 20,000 high school athletes to harvest summer crops. The country was facing a dire farmworker shortage because the bracero program, which provided cheap legal labor from Mexico for decades, had ended the year before.

Sports legends such as Sandy Koufax, Rafer Johnson and Jim Brown urged teen jocks to join A-TEAM because “Farm Work Builds Men!” as one ad stated. But only about 3,000 made it to the fields. One of them was a 17-year-old Carter.

He and about 18 classmates from University of San Diego High spent six weeks picking cantaloupes in Blythe. The fine hairs on the fruits ripped through their gloves within hours. It was so hot that the bologna sandwiches the farmers fed their young workers for lunch toasted in the shade. They slept in rickety shacks, used communal bathrooms and showered in water that “was a very nice shade of brown,” Carter remembered with a laugh.

They were the rare crew that stuck it out. Teens quit or went on strike across the country to protest abysmal work conditions. A-TEAM was such a disaster that the federal government never tried it again, and the program was considered so ludicrous that it rarely made it into history books.

Then came MAGA.

Now, legislators in some red-leaning states are thinking about making it easier for teenagers to work in agricultural jobs, in anticipation of Trump’s deportation deluge.

“I used to joke that I’ve written a story for the ages, because we’ll never solve the problem of labor,” Carter said. “I could be dead, and my great-grandkids could easily shop it around.”

I wrote about Carter’s experience in 2018 for an NPR article that went viral. It still bubbles up on social media any time a politician suggests that farm laborers are easily replaceable — like last month, when Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said that “able-bodied adults on Medicaid” could pick crops, instead of immigrants.

From journalists to teachers, people are reaching out to Carter anew to hear his picaresque stories from 50 years ago — like the time he and his friends made a wrong turn in Blythe and drove into the barrio, where “everyone looked at us like we were specimens” but was nice about it.

“They are dying to see white kids tortured,” Carter cracked when I asked him why the saga fascinates the public. “They want to see these privileged teens work their asses off. Wouldn’t you?”

But he doesn’t see the A-TEAM as one giant joke — it’s one of the defining moments of his life.

An old photo belonging to Randy Carter shows, seated at bottom right, his boss at the time, Francis Ford Coppola. “Everyone in this photo won an Academy Award except me,” Carter said.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., Carter moved to San Diego his sophomore year of high school. He always took summer jobs at the insistence of his working-class Irish mother. When the feds made their pitch in the spring of 1965, “there wasn’t exactly a rush to the sign-up table,” Carter recalled. What’s more, coaches at his school, known at University High, forbade their athletes to join. But he and his pals thought it would be the domestic version of the Peace Corps.

“You’re a teenager and think, ‘What the hell are we going to do this summer?’” he said. “Then, ‘What the hell. If nothing else, we’ll go into town every night. We’ll meet some girls. We’ll get cowboys to buy us beer.’” “

Carter paused for dramatic effect. “No.”

The University High crew was trained by a Mexican foreman “who in retrospect must have hated us because we were taking the jobs of his family.” They worked six days a week for minimum wage — $1.40 an hour at the time — and earned a nickel for every crate filled with about 30 to 36 cantaloupes.

“Within two days, we thought, ‘This is insane,’” he said. “By the third day, we wanted to leave. But we stayed, because it became a thing of honor.”

Nearly everyone returned to San Diego after the six-week stint, although a couple of guys went to Fresno and “became legendary in our group because they could stand to do some more. For the rest of us, we did it, and we vowed never to do anything like that as long as we live. Somehow, the beach seemed a little nicer that summer.”

Carter’s wife, Janice, walked in. I asked how important A-TEAM was to her husband.

She rolled her eyes the way only a wife of 53 years could.

“He talks about it almost every week,” she said as Randy beamed. “It’s like an endless loop.”

University High’s A-TEAM squad went on to successful careers as doctors, lawyers, businessmen. They regularly meet for reunions and talk about those tough days in Blythe, which Carter describes “as the intersection of hell and Earth.”

As the issue of immigrant labor became more heated in American politics, the guys realized they had inadvertently absorbed an important lesson all those decades ago.

Before A-TEAM, Carter said, his idea of how crops were picked was that “somehow it got done, and they [Mexican farmworkers] somehow disappeared.”

“But when we now thought about Mexicans, we realized we only had to do it for six weeks,” he continued. “These guys do it every day, and they support a family. We became sympathetic, to a man. When people say bad things about Mexicans, we always say, ‘Don’t even go there, because you don’t know what you’re talking about.’”

Carter’s experience picking cantaloupes solidified his liberal leanings. So did the time he tried to cross the U.S.-Mexico border in 1969 during Operation Intercept, a Nixon administration initiative that required the Border Patrol to search nearly every car.

The stated purpose was to crack down on marijuana smuggling. Instead, Carter said, it created an hours-long wait and “businesses on both sides of the border were furious.”

In college, Carter cheered the efforts of United Farm Workers and kept tabs on the fight to ban el cortito, the short-handled hoes that wore down the bodies of California farmworkers for generations until a state bill banned them in 1975.

By then, he was working as a “junior, junior, junior” assistant to Francis Ford Coppola. Once he built enough of a resume in Hollywood — where he would become a longtime first assistant director on “Seinfeld,” among many credits — Carter wrote his “Boy Wonders” script, which he described as “‘Dead Poets Society’ meets ‘Cool Hand Luke.’”

It was optioned twice. Henry Winkler’s production company was interested for a bit. So was Rhino Records’ film division, which explains why the soundtrack features boomer classics from the Byrds, Bob Dylan and Motown. But no one thought audiences would buy Carter’s straightforward premise.

One executive suggested it would be more believable if the high schoolers ran over someone on prom night and became crop pickers to hide from the cops. Another suggested exploding toilets to funny up the action.

“The mantra in Hollywood is, ‘Do something you know about,’” he said. “But that was the curse of it not getting made — because no one else knew about it!”

Colorado River water irrigates a farm field in Blythe in 2021.

(Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

Carter continues to share his experience, because “as a weak-kneed progressive, I always fancied we could change the situation … and that some sense of fair play could bubble up. I’m still walking up that road, but it seems more distant.”

A few weeks ago, federal immigration agents raided the car wash he frequents.

“You don’t even have to rewrite stories from years ago,” he said. “You could just reprint them, because nothing changes.”

I asked what he thought about MAGA’s push to replace migrant farmworkers with American citizens.

“It’s like saying, ‘I’m going to go to Dodger Stadium, grab someone from the third row of the mezzanine section, and they can play the violin at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.’ OK, you can do that, but it’s not going to work,” he said. “I don’t get why they don’t try to solve the problem of fair conditions and inadequate pay — why is that never an option?”

What about a reboot of A-TEAM?

“It could work,” Carter replied. “I was with a group of guys that did it!”

Then he considered how it might play out today.

“If Taylor Swift said it was great, you’d get people. Would they last? If they had decent accommodations and pay, maybe. But it would never happen with Trump. His solution is, ‘You don’t pay decent wages, you get desperate people.’”

He laughed again.

“Here’s a crazy program from the 1960s that’s not off the map in 2025. We’re still debating the issue. Am I crazy, or is the world crazy?”