This article contains spoilers for the series finale of “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

“The Handmaid’s Tale” ended in the early days of a new beginning, but with a battle that is still far from over. Is it hopeful? Time will tell.

After a planted bomb on a plane exploded and killed some of the top commanders of Gilead, the Hulu drama concluded Tuesday with June (Elisabeth Moss) and company figuring out a path forward as the occupation of the U.S. by the totalitarian regime begins to be dismantled, with liberation taking hold first in Boston and other parts in the Northeast. June, though, won’t rest until freedom reaches Colorado, where her eldest daughter, Hannah, is living under the regime.

While June’s central mission throughout the series has been to reunite with her daughter, the series ends with only the hope that it will someday happen. An emotional cliffhanger tied to logistics — a spin-off sequel titled “The Testaments,” based on the novel written by “The Handmaid’s Tale” author Margaret Atwood, in the aftermath of the show’s success, will launch later this year and focus on June’s daughter, who was renamed Agnes by her new family, and the other young women of Gilead.

Like the 1985 Margaret Atwood novel it’s based on, “The Handmaid’s Tale” provided a startling and harrowing look at what can happen when unchecked power and a totalitarian mindset, combined with religious extremism and social engineering designed to strip women of their autonomy, become codified. It was never supposed to feel like real life. But Yahlin Chang and Eric Tuchman — longtime series writers who took over as showrunners for the final season from co-creator Bruce Miller, who has pivoted to adapting “The Testaments” — are aware that some viewers see similarities between the fictional cautionary tale and reality.

The Times spoke with Chang and Tuchman about the real world parallels and bringing the series to its conclusion with Miller, who wrote the finale. Here are edited excerpts from the conversation.

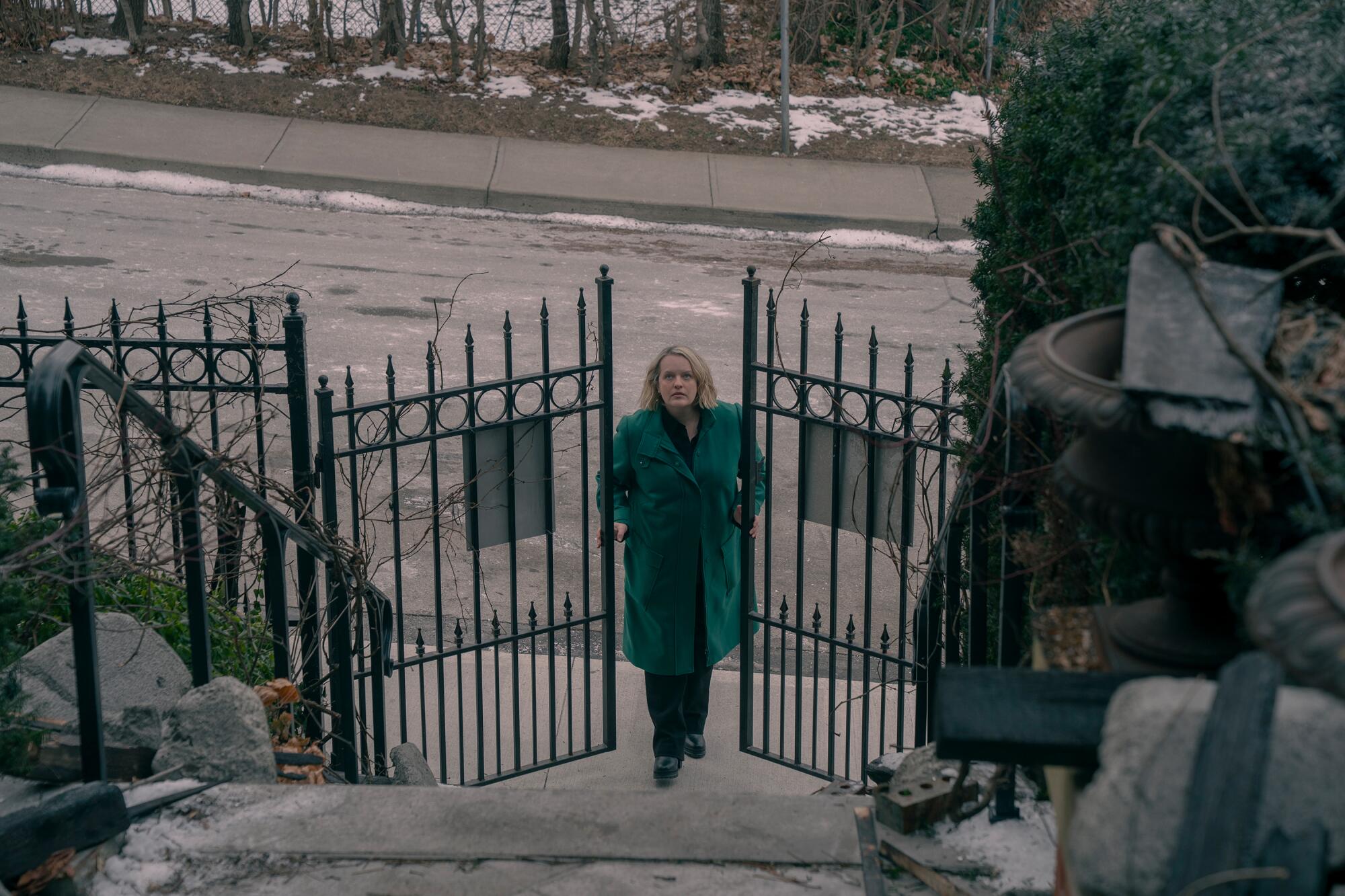

In a scene from the series finale of “The Handmaid’s Tale,” June (Elisabeth Moss) reflects on her experiences in Gilead and decides what to do next.

(Steve Wilkie / Disney)

June returns to the Waterford home where she records her monologue, a callback to what we hear in the very first episode. Was that always envisioned as the closing scene?

Chang: Originally, Bruce envisioned it as the penultimate scene, but it became the ultimate scene because it became so clear, in my head anyway, that June was telling the story to Hannah and for Hannah, and that the whole series we’ve been watching has actually been her story to Hannah. Given that our hands were tied, unfortunately, and we could not bring June and Hannah together because of “The Testaments,” which was something that we really struggled with — I struggled with, speaking for myself — not giving people what they wanted or what I wanted, the idea of her telling the story to Hannah was just so emotionally captivating. I don’t think that Bruce was so worried about not seeing Hannah. There’s this whole sequel that focuses on Hannah. And Lizzie had a big part of this too; she influenced the writing of this scene between June and Holly [June’s mother, portrayed by Cherry Jones], where it evolved into a scene where Holly says, “This story is for the people who have lost, who have not gotten their children back; this is for them.”

Tuchman: Knowing we couldn’t reunite June and Hannah, it was heartbreaking because we’re certainly aware of how much the audience was longing for that. It seemed to be what was driving June over the course of the whole series. But once we found out that we couldn’t do that, that there was that boundary that we had to respect, when I think about it now, it shifted what her emotional engine became: What does it mean to keep going when you don’t get what you want and what you are hoping for, and what if that might never happen? It actually feels like a really powerful message now — that you keep going; you never stop loving and hoping and wishing and dreaming and whatever obstacles come your way, certainly as a parent, you’re going to do whatever it takes to keep moving forward. Just to see Lizzie climbing those recreated steps of the Waterford house to Offred’s room and to end up sitting in that window seat in that iconic pose, felt like such an almost overwhelmingly emotional experience because it’s a complete full circle.

News broke in 2018 that Margaret was writing “The Testaments.” It had been in development as a sequel series, but an official order from Hulu didn’t arrive until April of this year. When did it become clear that you needed to shift how you wrapped “The Handmaid’s Tale”?

Tuchman: If I’m remembering correctly, Bruce got an early look at that manuscript, so we knew pretty early on about this concern that we might not be able to reunite them. I think Hulu was very enthusiastic about trying to produce a sequel series, so the restriction about Hannah, we knew about by Season 4. We never stopped thinking about ways around it. Certainly this season, we had many pitches — and Yahlin had fantastic pitches, especially — about how to maybe satisfy that reunion without quite really reuniting them.

Care to share one of those pitches?

Chang: Just as a mom myself, I kept thinking about, “What could I do, knowing that there’s the sequel.” I had pitched a couple deep flash forwards, like deep into the future. So it’s like “The Testaments” would have had to run for like 30 years. But I totally understand why we couldn’t do it.

A group of handmaids gather just as Gilead cracks down on the rebels in the series finale of “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

(Steve Wilkie / Disney)

What we get is June continuing the fight because, as she says, they are never going to stop coming and not fighting is what brought about Gilead and it needs to be broken. Do you consider the ending a triumphant one? Is this a victory for June?

Chang: I think it’s triumphant because she survived and she’s still fighting. But it’s bittersweet because she doesn’t get what she wants. It’s like life. The power of the show has always been that it’s like life. I know Bruce very much didn’t want the finale to feel like [raises voice to sound more authoritative], “This is a television series finale.” He wanted to feel like this is what happens the next day. And I think you get that sense that we are dropping in on these characters on this day.

When it came to the rebellion, how did you think about what that would look and feel? People on social media were saying they were hoping for another red wedding; for the men to experience torture and suffering. We got some of that, but not to a high degree.

Chang: Well, because there is a very famous “Game of Thrones” episode called “Red Wedding,” I never wanted it to be a red wedding like that. Full disclosure, I did originally envision seeing a bunch of murders, but honestly, we didn’t have the time or the money to shoot them. It’s a question that you do always have with producing television, when you have a world of limited time and limited budget: How do you most effectively tell the story? It felt like what you want is this very satisfying murder that June does of a very vile, satisfying character, [Commander Bell], which is part of the reason we cast Tim Simons. When we actually [conceived of] Bell from the very beginning, we used Tim as a model.

Tuchman: We called him Jonah in the room because of “Veep.” We couldn’t call him Jonah Bell eventually, but that was his name in the room.

Eric, with Episode 9, was there a lot of debate over how to deal with these commanders? Was it always going to be death by a bomb on a plane?

Tuchman: It was an idea that we came up with very early on when we were first breaking the season. I think I mentioned it one day in the room. I know for sure that I pitched Lawrence bringing this bomb on. I think I also pitched Nick showing up unexpectedly at the same time. That was something that we were aiming for as a big tentpole event later on in the season.

To take a step back to talk about the revolution on the show, I think people may, deservedly, have wanted more bloodlust, but you have to remember what show this is. We wanted to stay true to the kind of storytelling that has been representative of the show, a very character-driven, emotional experience, which is not to say we haven’t had spectacle and we haven’t had action. We wanted to provide just enough of that in the in the ninth episode, where you see the uprising happen and ignite, but also remain true to June’s point of view. We don’t typically leave her to go off into other events. But what was very satisfying for me, and what I think we really accomplished this season, is getting June and Moira [Samira Wiley] back in that handmaid’s outfit, back to the beginning. It had to be the handmaids to take down Boston. It’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” — June had to be vital, essential in that uprising. She had her very last opportunity to spark the revolution, she grabbed it on that execution stage and she did it.

Serena (Yvonne Strahovski) and Aunt Lydia (Ann Dowd) in the series finale of “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Co-showrunner Yahlin Chang on their journeys in the final season: “We never talked in terms of what is their redemption arc. Those are characters who have willful blindness to what’s going on, and it was about how do you crack open their eyes to see the truth, then how would they react to it?” (Steve Wilkie/Disney)

What did you and the writers want out of the Serena [Yvonne Strahovski] and Aunt Lydia [Ann Dowd] arcs? They were significant players to the harm women faced in Gilead. What was the conversation on what justice or redemption looked like for them?

Chang: We never talked in terms of what is their redemption arc. Those are characters who have willful blindness to what’s going on, and it was about how do you crack open their eyes to see the truth, then how would they react to it? In our show, the thing is that our villains suffer not from being inhuman, but being too human. They have all the insecurities and fears and weaknesses of humans. For Serena, it’s this narcissism and self-justification. For Lydia, it’s also that she’s justifying everything by saying it’s God. As the seasons went on, it was about peeling those away so that they could finally see the truth. Once they saw the truth, we felt like they would probably do the right thing as long as they understood how horrible it was what they were doing.

Tuchman: One thing we always talk about is one of the virtues of June is that she can see the humanity in everyone — at least, she hopes to touch the humanity even in the most despicable characters. It’s through June’s influence, ultimately, that she breaks through to Lydia in Yahlin’s episode. She’s speaking in a heartfelt, genuine way, woman to woman, and opens Lydia’s eyes. In the following episode, there’s the scene between June and Serena, where Serena has to give up the information that’s going to take down that plane; you see June using Serena’s own devotion to God and to her child to wake up and realize there’s no hiding anymore from what’s the right thing to do. It’s that influence from our central character that really transforms these two other women.

In their final exchange, Serena apologizes for what she’s done and June forgives her. Were there different iterations of that exchange?

Chang: The first draft of [Episode] 10 did not bring the June-Serena scene to that place of forgiveness, but it felt important that we get to a milestone in their relationship in the final episode. That’s all Serena has been after. Like it or not, she has been seeing June as her vehicle for redemption and really needs it and really cares about this relationship. She’s so desperate for it, and then June grants the forgiveness as like a gift, and also because of what she [Serena] did in Episode 9.

Nick (Max Minghella) and Lawrence (Bradley Whitford) in the series finale of “The Handmaid’s Tale.” (Steve Wilkie/Disney)

You spoke earlier about willful blindness, and it made me think about Nick [Max Minghella]. I struggled with making sense of this character that I thought I knew and the decisions he made in the end. But maybe it speaks to my willfull blindness.

Tuchman: We are very aware that people are very invested in the Nick-June relationship, for good reason. Max Minghella is so compelling and charismatic. He has unbelievable chemistry with Lizzie. And Nick, as a character, has been her savior time and again. He provided a source of love and comfort for her. He stuck his neck out to help with Hannah. He’s done all those wonderful things and that’s what June has seen; she has not chosen to think about what he might be up to when he’s not helping her out. I would just like to remind all of us of a few things that played on-screen because, granted, we didn’t show a lot of his life off-screen away from June, but we did hear in Season 3 that the Swiss delegation refused to speak to Nick because he’s a war criminal who can’t be trusted. He rose from being a driver to a commander. They don’t just dole out those promotions too easily. And on top of all that, he’s been given many opportunities to come to the light and be free and live in Canada. And he chose not to. What we wanted to do this season is have June — and the audience — be confronted with who this person is for real and realize there is no such thing as a good Nazi, even if that Nazi might be adorable and helpful when you need him.

I understand that people are upset, but we were just trying to be honest. We gave Nick one last chance before he decides to get on that plane that seals his fate and tells us is he going to be all in with Gilead or is he going to decide to turn around and call Mark Tuello [Sam Jaeger] and say, “Come get me.” He doesn’t. That’s true to his character. He’s got the safety and the status that he wants in Gilead. To me, he’s been a consistent character. He’s been who he is all along and we, like June, were swept away and didn’t see the truth about him.

Chang: Nick chose every day to be a commander. We’re getting to the idea that people aren’t all good or all bad, they exist in shades of gray. Also, the idea that him betraying the plan to Wharton, at that moment, it wasn’t like, “Oh, Nick’s been a hero, and then suddenly he makes this decision and he’s evil.” He figured out the odds and he was under emotional distress and he couldn’t come up with something else, except for the truth, because Wharton had put together so many pieces. He made a split-second decision that, in retrospect, was maybe the wrong one. He’s human. It’s not like suddenly he’s your mustache-twirling [villain]. He’s the same person he’s been throughout.

Commander Lawrence’s story comes full circle in a way. He is an architect of Gilead and makes the ultimate sacrifice to bring about its downfall by getting on that plane with the bomb.

Chang: Lawrence, from the very beginning, was this very enigmatic figure. He was an architect of Gilead. The way we envisioned him was as this obscure economics professor tooling away in the corner of a university. His ideas were basically taken by Gilead and taken seriously and it was exciting for him to remake the world. He really felt that he saved humanity. He never believed in the God stuff, but he did believe that the God stuff and the religion stuff was very helpful in terms of getting people to comply because they needed more of a spiritual reason to comply with Gilead. And what he did worked. But of course, he has had these huge regrets. He was playing both sides. He’s both a commander, but then to feel good about himself and to feel OK, he’s voting the right way, secretly doing these other things. What we show is that he can’t exist with a foot in both worlds all the time.

Tuchman: He’s always said he wants to clean up his mess. He has a lot of guilt about what happened to his wife, Eleanor, who’s a true love for him. He’s been desperately trying to make New Bethlehem work, his idea of a kinder, gentler Gilead, and then finds that he was duped by his fellow commanders and his pet project was nothing but an ambush to entrap more refugees. At the plane, he’s presented with an opportunity to strike back against these guys who’ve betrayed him and who are horrific and will end up brutalizing and massacring a bunch of people if he doesn’t stop them. Then they show up and he has a chance to concoct some excuse to get out of it, but I feel at that point, he rises to the occasion and sees that this is a practical way to make a genuine difference — if he can stop these militant aggressors and do something to dent Gilead, to help break Gilead, he’s going to take it.

June (Elisabeth Moss) returns to the Waterford home in the final moments of “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

(Steve Wilkie / Disney)

The series was developed in the Obama era, but it is often discussed in the context of the Trump administration. It’s invoked on social media as people repost or comment on the headlines of today — whether about women being charged for having miscarriages, the overturning of Roe [vs. Wade], deportations or lawsuits against the press. You’ve said before that the goal with the show is not to make a statement about current politics, but aren’t politics inherent to the story?

Chang: It’s so scary because every day — even just yesterday, I was reading about these conservative proposals to get parents to stay home with their kids, and we’re meaning really moms to stay home with their kids; it’s like something we would make up. It’s this weird thing, when people watch a TV show that you made, you really want it to feel real and not made-up. That’s the No. 1 goal. It’s weird to have the world and current politics as it stands help us in that goal. The truth is the world of “The Handmaid’s Tale” in Gilead is incredibly weird and unlikely. It feels like if Eric and I had just gone in and pitched it, “All right, there’s going be these handmaids in red rose, and there’s going to be a ceremony …” and there was no book, we would be laughed out of the room because it sounds so crazy. But it became this iconic book because it speaks to some really dark undercurrents and elements in our world involving misogyny, the oppression of women and fascist desires.

There’s that Margaret Atwood quote that defines the whole show that we use, which is, “Nothing changes instantaneously. In a gradually heating bathtub, you’d be boiled to death before you know it.” Because that’s true, you do need novels, shows, movies and plays that jolt you out of that, where you go, “Wait, this isn’t OK. This could be leading somewhere bad.” I didn’t realize when I started working on this show that I would have fewer rights than I do now. Even I, in Season 2 in 2017, was like Roe vs. Wade will never be overturned. Even working on the show, I’m continually shocked. It has to do with what we were talking about before with Nick and normalizing fascism. He has been a fascist this whole time, but we so normalized him and made him a romantic hero that we forgot. We do have this tendency to continually normalize every outrageous thing that happens. I’ve joked with Eric that if people call the show a cautionary tale, then we really failed in our mission to be a cautionary tale because life is worse now than it was before.

Tuchman: I remember when we first started the writers’ room in Season 1, this was 2016, and I thought, “Oh, we’re adapting this great, classic piece of literature,” which was known as speculative fiction about a dystopia, and we just wanted to tell the best version of that story as a TV show. Suddenly the show that might have been a cautionary tale became a reflection of our real world and our country, and it was a very different vibe. It became, like it or not, a cultural touchstone for what was going on in the country. The fact that we’ve come around and, by the end of the show, I can’t even say back where we started, I dare say we are worse than where we started. We have failed miserably, if we were at all meant to be the cautionary tale, because enough people were not watching, listening and absorbing and thinking hard enough, in my opinion, about the dangers of not addressing the warning signs. I don’t know what it says about us as a nation if more than half of the voters decided that they were OK with with this slide away from democracy. If the show has taught us anything, it has taught us that freedom is precious and democracy is fragile.

Chang: People are saying, “Is it a ripped-from-the-headlines kind of thing where you read stuff and then you would put it in the show?” The answer to that is no. What’s really scary about it is that we were just imagining the worst of the worst of what could happen if you have the wrong people in power, then the world kept catching up to it. The more that authoritarianism is seeming to creep into our world, there’s a part of me that’s like, “Oh God, are Eric and I are going to end up on the wall?” I was never scared about that before.