Aside from their commercial prowess, “A Minecraft Movie” and “Sinners” don’t seem to have much in common. One is a PG-rated, special effects-heavy comedy based on a video game with a huge fan base, and the other is an original Ryan Coogler-directed, R-rated period thriller with vampires.

However, both went viral online in ways that drove their success at the box office, in a boon to struggling theater owners and the studio that backed both projects, Warner Bros., which was in dire need of a pair of wins after a rough several months.

“Minecraft,” co-produced by Legendary with a reported production budget of $150 million, has grossed $816 million worldwide, while the acclaimed $90-million “Sinners” has collected $162 million. The latter film grossed $45 million domestically during its second weekend, a drop of only 6% from its opening — a clear sign that the movie has become a must-see.

The common thread is that both films created a wave of excitement on social media that the studios were able to capitalize on to create a cultural moment.

With “A Minecraft Movie,” for example, screenings took on a “Rocky Horror Picture Show”-like atmosphere for Gen Z moviegoers, with audiences shouting lines back to the screen and videos of the mayhem taking over TikTok. (If the phrases “Chicken Jockey” and “I am Steve” mean nothing to you, it’s probably easier to Google it than to have me explain.)

The madness in the auditoriums has understandably irked theater operators and unsuspecting patrons, especially when one attendee brought a live chicken into a showing. Nonetheless, it has clearly contributed to the film’s popularity, and Warner Bros. and Legendary are cashing in on the momentum. On Monday, the studios announced a series of “Block Party Edition” screenings, encouraging fans to sing and talk during the movie.

For “Sinners,” the tenor of the reactions have been far different but were no less helpful for the box office. The company was able to lean on the enthusiasm and raw, emotional responses that moviegoers, including social media influencers, were having to the film.

None of this was expected, said Warner Bros. marketing co-lead Christian Davin. But it helped expand the audiences beyond people who were already fans of the “Minecraft” game, Coogler, “Sinners” star Michael B. Jordan and horror movies.

“At the outset of ‘Minecraft,’ did we think that people were gonna be screaming ‘Chicken Jockey’ back to the screen on opening weekend? Absolutely not,” Davin said. “At the outset of ‘Sinners,’ did we think that there was going to be this entire discourse on TikTok about various scenes? … But as we started to see those things, we started to fan the flames.”

The two have key lessons for marketers as they contend with intense competition for audiences’ attention and the unique interests and habits of younger consumers, which few people in Hollywood seem to understand.

At a time when audiences’ attention spans are short and constantly pulled in multiple directions, studios have to work harder than ever, especially in the last days of the campaign, executives said.

The Gen Z audience — so crucial to “A Minecraft Movie’s” performance — is suspicious of anything that feels overly corporate or inauthentic, which can pose challenges for marketing teams.

This was certainly the case for the early “Minecraft” campaign, which got off to a rocky start. The first teaser trailer was pilloried online by fans of the game, who were fiercely protective of the property. “Minecraft,” after all, is a game that rewards creativity, so players tend to feel a sense of ownership. What are you doing to our thing? the message seemed to be.

So the studios had to adjust. The second trailer included a cheeky intro (“Minecraft trailer, take two”), which acknowledged the misstep. From there, fans started to come around, sometimes begrudgingly. A key factor, executives said, was the involvement of Mojang Studios, the Stockholm-based developer behind “Minecraft,” which promoted the movie heavily, including with activations in the game itself.

From the start with both “Minecraft” and “Sinners,” it was all about listening to the audience and being willing to adapt, said Warner Bros. Pictures global marketing co-lead Dana Nussbaum. Another instance was the introduction of a Lava Chicken “menu hack” at McDonald’s through the companies’ co-branding initiative (again, if you know, you know).

“The audience will tell you every single time,” Nussbaum said. “And I think as long as you’re listening and you’re unafraid of being flexible, that’s where you can win.”

Nussbaum and Davin were tapped to lead Warner Bros.’ film marketing efforts following the dismissal of marketing chief Josh Goldstine in January, which was widely seen as a risky move, coming ahead of a high-stakes slate of films including “Superman” from James Gunn and “One Battle After Another” by Paul Thomas Anderson.

The people who made “Minecraft” — including stars Jack Black and Jason Momoa and director Jared Hess (“Napoleon Dynamite”) — understood that the campaign wouldn’t work if players felt that they were being force-fed their own game back to them.

That was part of the rationale behind calling it “A Minecraft Movie,” rather than “The Minecraft Movie,” said Legendary Entertainment marketing chief Blair Rich.

Getting the quirky comedy right was also crucial. The “Minecraft” example is particularly instructive because of what it says about Gen Z, which responded to the chance to go out and celebrate something their parents don’t necessarily understand.

“For these fans, the game is such a strong community … They have pride of ownership, and it’s their game. It’s not some corporation’s game,” Rich said. “And so the marketing had to always draft off of that sensibility.”

For both movies, influencers played an important role. Podcaster and movie influencer Juju Green (a.k.a. Straw Hat Goofy), for example, interviewed Coogler for “Sinners” and promoted the film with video breakdowns on social media. Those moves helped stoke interest among Black audiences and cinephiles more broadly.

“A Minecraft Movie’s” marketing strategy leaned heavily on digital influencers, even bringing some on set. Dozens of Minecraft gaming influencers were brought to the movie’s global premiere in London, where they had access to talent. The companies made sure to get not just the video game influencers but also general entertainment and family creators.

That helped lead to a meme-fueled campaign. One influencer went viral after singing a bombastic parody of “Pure Imagination” with catchphrases from the movie.

It’s the kind of thing that works for young audiences. According to a recent Deloitte survey of U.S. consumers, the majority of Gen Zers say they feel a stronger personal connection to social media creators than to TV personalities and actors.

Studio executives have been picking over both movies for tangible lessons as box-office revenue overall struggles to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Hollywood labor strikes and the long-term decline in theatrical attendance. Are video game movies replacing superhero movies? Does “Sinners” show that audiences want more original films?

One key takeaway is that audiences seek experiences in theaters that can’t be replicated at home. “A Minecraft Movie’s” audience participation aspect is an obvious example.

That doesn’t mean every movie needs a “Gentleminions” campaign or “Wicked”-style sing-along. “Sinners” has this advantage too but in a different way, where audiences are having intense emotional responses in the theater, Nussbaum noted.

“It was an incredibly emotional and visceral reaction that people were having and were wanting to have in groups and in communities,” she said. “And I think that was what was so rewarding about it.”

Newsletter

You’re reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

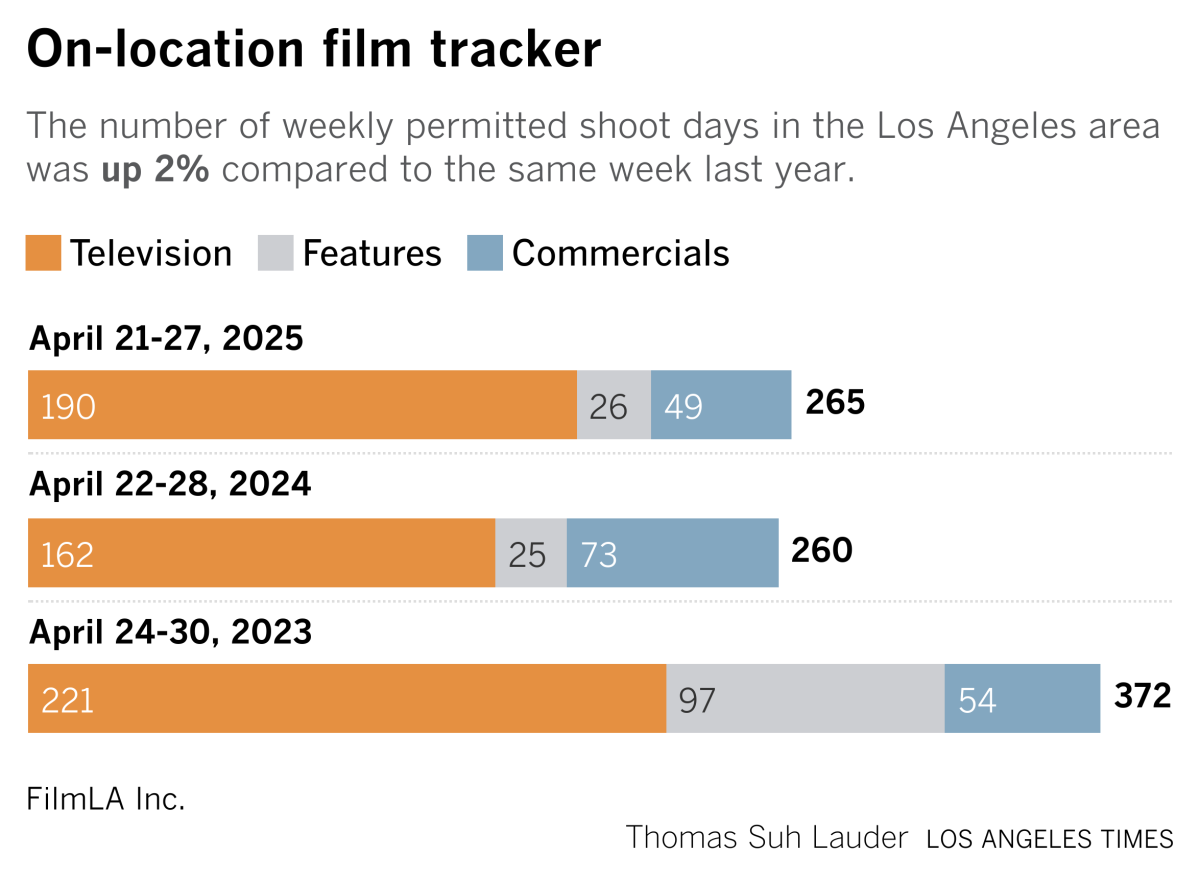

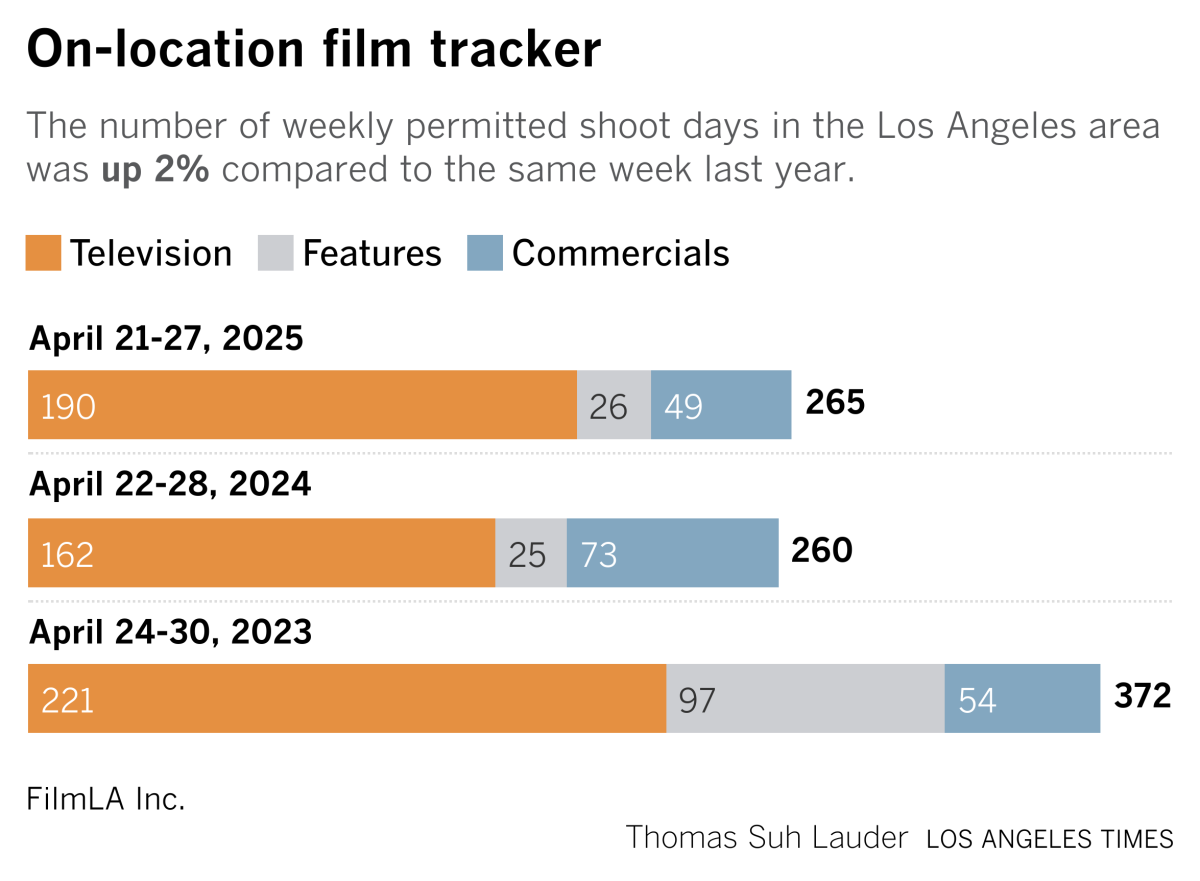

Film shoots

On-location filming was up 2% last week compared to a year ago.

Finally …

Listen: New music from Julien Baker & Torres.