It is April 4, 1975, a beautiful, sunny day in Saigon – soon to be renamed Ho Chi Minh City. But there is violence and turmoil in the air. The Vietnam War is in its final weeks, and North Vietnamese forces have surrounded the city, inciting chaos as the South Vietnamese populace and its US allies scramble to evacuate those most at risk of reprisals.

Untold numbers will ultimately be left behind, but more than 100,000 politicians, military figures, and others associated with the now-rapidly losing side will be airlifted for resettlement. Among the latter are dozens of orphaned infants and children, many of whom are “Amerasians” born of relationships between Vietnamese mothers and American soldiers, now destined for placement with families in the United States and other countries around the world.

In one plane – a hulking C-5A US military transporter – “the children were secured two to a seat in the troop compartment,” wrote lieutenant flight nurse Regina Aune, who was on the flight. Those in the cargo compartment “were placed on blankets and secured to the floor with litter straps and cargo tie-down straps”, she explained in her book, Operation Babylift: Mission Accomplished, published in 2015 to mark the mission’s 40th anniversary.

Many of the children are handed over by young Vietnamese women sobbing at the prospect of relinquishing their babies to “strangers and foreigners from another country, speaking a language they could not comprehend”.

Just after 4pm, the plane departs from Tan Son Nhut airport, carrying nearly 300 people, but mere minutes after takeoff, the locks on the rear loading ramp fail, causing the cargo door to separate and the plane to decompress 7000 metres (23,000ft) in the sky. Aune barely escapes being sucked out, and later recalls seeing her colleague “hanging by his arm, the rest of his body dangling into the void”.

The flight controls have been badly damaged, and the plane begins a rapid descent. It is clear that the craft will not be able to make it back to the airport, so the pilots aim for a nearby rice paddy, throttling up to lift the nose before touchdown.

When it does hit the ground, the plane skids before skipping back aloft like a stone, then smashes into a dyke and breaks into four pieces. Aune is tossed along the entire length of the compartment, sustaining a broken foot as well as other injuries.

Once she manages to make her way outside, she sees “wreckage and debris in every direction”. The flight deck is 90 metres (100 yards) away and upside down. Her dangling colleague managed to keep his grip, and he now splints his broken leg with a crutch and seatbelts before assisting with the rescue.

A human chain forms amidst the devastation to pass surviving children to rescue helicopters, and Aune helps shuttle infants to safety until she faints. Later that year, she will be the first woman to receive the Cheney Award, a US Air Force medal for valour and self-sacrifice.

But regardless of her and others’ efforts on that day, 138 were killed in the plane crash, 78 of them children.

It was the first official flight of Operation Babylift – a US government-sanctioned effort to evacuate the orphanages of South Vietnam – and the highly publicised disaster thrust the mission into the international spotlight. In its wake, thousands of potential parents in the US and elsewhere signed up to receive adoptees, and the youngsters – some war orphans, some the abandoned offspring of American servicemen, and others given up by families fearing for their wellbeing and safety – were scattered across new homes in distant lands.

In the end, more than 3,000 children would be taken abroad over the course of three weeks. While the legacy of the operation later came into question when it was found that some of the adoptees had living parents or relatives who had not, in fact, consented to their removal, now on its 50th anniversary, one thing is undeniable – it reshaped the identities and families of those affected by it for a lifetime.

A chaotic escape

At the behest of organisations working with children in Vietnam, such as the Holt International adoption agency, the philanthropic Friends of Children of Vietnam, and several Catholic orphanages and other groups, US President Gerald Ford announced the plan to evacuate adoptees from Saigon on April 3, the day before the crash. It soon became apparent that military efforts would be too slow as resources were stretched thin, so private flights operated by Pan Am and World Airlines joined the campaign.

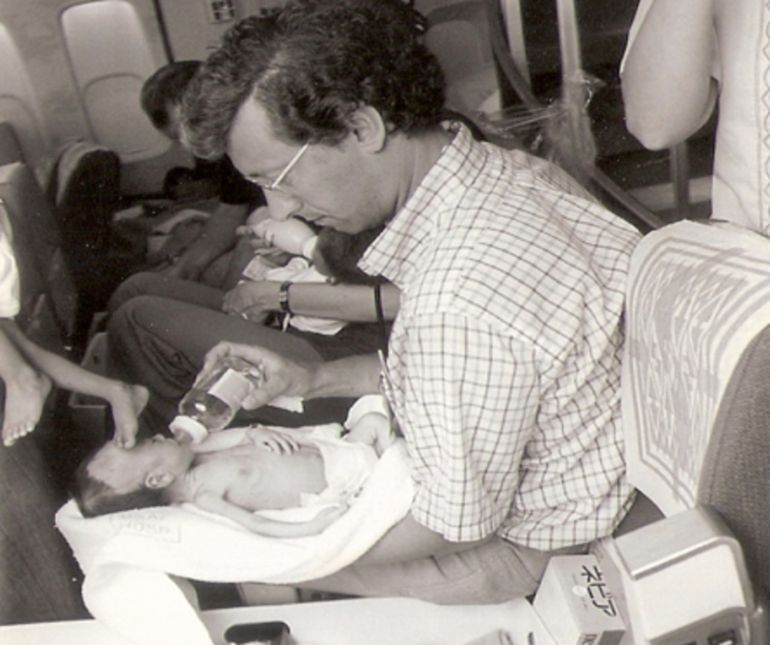

“The people who deserve recognition never got it and never will,” Frederick M “Skip” Burkle Jr, medical director of the little-reported airlifts undertaken by World Airlines, tells Al Jazeera, referring to the many nurses, flight crews, and support staff who participated in the airlift.

By the time of Operation Babylift in 1975, Burkle, now 84, had completed a combat tour in Vietnam as part of the medical corps, running a hospital in the battle-torn front-line region of Quang Tri.

“People came from all over the northern part of south Vietnam to see me because nobody could take care of them,” Burkle recalls. These patients included everyone from sick local children to wounded soldiers. “And these were wonderful people. We laughed together. We joked together. The war was going on, but we didn’t discuss the insanity because we couldn’t understand that. It did not make any sense, but you had to function in an environment that did not make any sense.”

After this he attended the University of California, Berkeley to study global health, a specialisation in which he would become an important figure, and it was there he received a phone call asking if he would join a medical team that was being put together by World Airways, to assist with the evacuation of orphans from Saigon.

“I said I had to make sure I could get out of my classes,” Burkle says. He told the caller that he had previously overseen a hospital in Vietnam and spoke the language, “and they said, Wow! Would you be the director?”

The team was quickly dispatched to the Philippines where the US had maintained a strategically vital base for more than 70 years. Operation Babylift was already in full swing, but they were told that the airport in Saigon would no longer receive civilian aircraft. North Vietnamese forces had already taken Xuan Loc, the last line of defence before Saigon, just two hours away, and the capital was under sporadic attack.

“Everyone was looking around and they turned to me and said, You know the language. Would you be willing to go in?” Burkle recalls. “And it was actually the last thing I wanted to do, because I knew that if my wife had known she would have said no.” He described how she “went through hell” when he was previously in Vietnam after receiving false reports of his death.

But he agreed anyway, and their flight continued from the Philippines, arriving in Vietnam on April 26 – three days before the operation’s final flight and four before the Fall of Saigon. During its approach to Tan Son Nhut airport, Burkle saw rockets crisscrossing through the air as they passed over the wreckage of the first Babylift plane.

“The radio was yelling at us, Don’t land, don’t land,” says Burkle. “It was not safe. We came down hot,” making their approach as fast as possible to avoid taking fire.

Saigon had swelled with millions of refugees and forward North Vietnamese forces, and now Burkle had to make his way to orphanages scattered across the city to find infants and verify lists of those slated to go.

“So I went to about five of these. I don’t know how I did it. I don’t know how I was allowed to do it. The North Vietnamese obviously knew I was there and were following me and could have stopped me at any time, but I think they wanted to know what was the bigger picture, and what was I going to do with all this?”

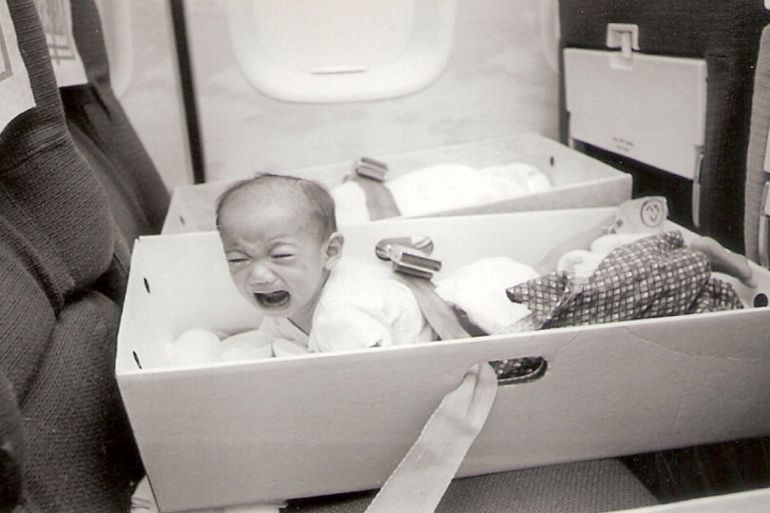

Each orphanage was told to bring the children to Tan Son Nhut airport the next morning, and once they arrived they were divided between two planes. The most critically ill – malnutrition was rampant after years of the war’s privations – were placed in first-class seats, while a novel solution was devised for securing infants in the cargo hold.

“We had file boxes, which, believe it or not, were just great to put an infant in and lay them on their back,” says Burkle, referring to cardboard cartons used for organising paperwork. “The planes were the C-130s that open from the back and have straps, and the boxes had holes to hold onto, so I said put the straps through the holes and just line them all the way up. We got in as many as possible. On the sides and on top of each other.”

More than 300 children, most babies and infants, were put on board.

There were also a number of Vietnamese adults, and a “cool, calm, and collected” American in a Hawaiian shirt who told Burkle: “Thank god, we’ve been waiting for you. I’m CIA. These people are ours and we’ve got to get them out.”

The situation didn’t get any less chaotic from there. Just before takeoff, a Vietnamese saboteur was discovered and prevented from placing a bomb on one of the planes. At some point, the pilot began vomiting, explaining that he “just can’t stand the sight of sick kids”. Then, when they finally took off fast “at 90 degrees – all we could see was blue sky and the engines were roaring”, the cockpit windshield began to crack under the pressure. But eventually, both planes made it to the safety of Clark Airbase in the Philippines, roughly three hours away.

“I hadn’t slept at all,” Burkle chuckles. He’d spent three days preparing the team, gathering orphans, and making the trip, “so I was pretty exhausted”.

There, the children were moved onto a single 747 which carried them to San Francisco, where public health officials were initially reluctant to let the children deplane due to concerns over potential contagions. But they relented, and Burkle was allowed to return home to Oakland, but not before “someone from the State Department said, ‘you’re not to talk to anybody about this at all. This did not happen.’”

His wife picked him up from the airport and he finally got some sleep before attending class the next morning. “Nobody knew a thing about what I’d been up to for the last four days.”

Burkle went on to have a prominent career in global medicine and was frequently tapped to provide health crisis assessments in war zones and other disasters in places like Myanmar, Somalia and Iraq. In the case of Iraq, he was named the first minister of health for the Coalition Provisional Authority by President George W Bush in 2003, but was promptly fired after Burkle deemed the country a public health emergency due to its devastated healthcare infrastructure.

“I didn’t last very long because I declared that what Bush was doing was wrong,” he explains, “and they had to declare Iraq a public health emergency or they were going to lose a lot of lives. They didn’t like that, so I was sent out. And of course it turned into one of the worst public health emergencies ever.”

Picked out ‘like puppies’

Public opinion of the operation during and immediately following it was positive, and there was a general assertion that a great humanitarian victory had been achieved. But it didn’t take long before aspects of it came into question.

Almost immediately, there were reports of Vietnamese mothers and relatives protesting that they had handed over their children for care without realising they would be evacuated from the country. Most of these adoptees would not reunite with their families for decades, if ever.

Then there were issues with the adoption process itself. While some agencies had secured homes for children under more or less normal adoption circumstances, children without placement were gathered in San Francisco, where one Vietnamese translator later said aspiring parents were picking them out “like puppies”. Many had paperwork that was mixed up, forged or nonexistent, making identification difficult and complicating future efforts to reconnect with birth families.

And in some cases, children were placed in homes with people who were entirely unfit to be parents. Later, there would be reports of abuse, neglect and racism.

But it would be inaccurate to describe Operation Babylift as either entirely benevolent or inherently harmful. As many adoptees have explained, the reality was much more complicated.

The search of a lifetime

In the years that followed, the adoptees – most of whom now resided in the US with some in Australia and Europe – retained few to no memories of Vietnam.

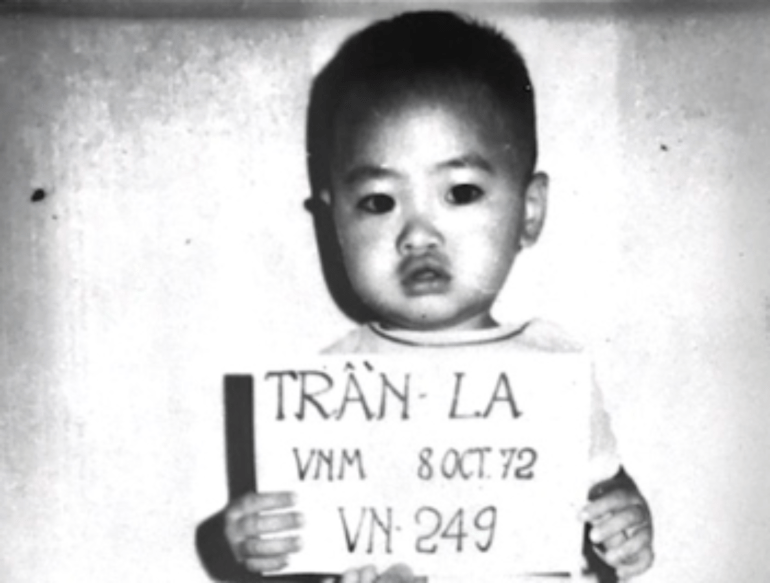

“Growing up, I just wanted to be that all-American boy,” says Saul Tran Cornwall, whose Vietnamese parents relinquished him to a Holt orphanage shortly after his birth in 1972. “I wanted to fit in and be popular. I didn’t know what assimilation was or meant, but that’s what I was doing. I knew I was from Vietnam and that I was adopted, but I didn’t really explore the cultural heritage of that.”

Canh Oxelson, born in 1971 to a Vietnamese mother and African American soldier, had a similar experience early on. “I was an all-American swimmer. I wasn’t Black or Asian or white. I was a swimmer. That’s how I saw it.” But once Oxelson graduated from university, new questions about his identity emerged. “I figured, gosh, I’m not a competitive swimmer any more and never will be, so who am I?”

During his high school years, he had dreamed of making it to the Olympics, where – just maybe – his birth parents would recognise him. Now that swimming was over, he began to seriously consider searching for them.

As it turned out, his adoptive parents had been saving money for years for just such an eventuality, and, in the late 1990s, as he was approaching the age of 30, they went to Vietnam as a family where they visited the Sacred Heart Orphanage in the city of Da Nang.

“It was one of the first times an adoptee had come back with their adopted family, so for them it was like seeing what they had hoped for and all they sacrificed for as nuns – they got to see it come full circle.”

For Oxelson – now 53 – it was a powerful experience.

“Adoption is like a story that’s being told to you,” he explains. “And it wasn’t until I met people who were there at the beginning that I thought ‘oh my gosh, the story that I’ve been told for years is true!’ To see my name written in the registry was stunning. I’ll never forget: Number 867, and it had my full birth name, my birthday, and the date I left the orphanage.”

But at the time, that was as far as his search went. It would take over a decade before he would finally reconnect with his birth family.

Cornwall had a similarly prolonged path to finding his.

It wasn’t until college (and shortly after spending two years working in post-adoption services for Holt – the very agency where his journey began as an infant) that he connected with Vietnamese and Asian refugees, prompting him to delve into his heritage. So in 2000 at the age of 28, he marked the 25th anniversary of Operation Babylift by joining the Holt Motherland Tour through Vietnam. Visiting Vietnam, however, struck him like a normal tourist trip as he felt no connection to the country, and his early endeavours to find his family proved fruitless.

Sixteen years later, he returned to Vietnam, this time with his adoptive father, who had served in the war. And while “that was really special, by 2016 I was kind of done with Vietnam”. He’d been three times, and online and DNA searches had turned up little beyond some distant relatives.

But then in 2022, he received a Facebook message from fellow adoptee Trista Goldberg, founder of Operation Reunite – an organisation partnered with FamilyTreeDNA that works to help Vietnamese adoptees reconnect with their birth families.

“You might want to sit down for this,” her message read. “We have some news.” It appeared they had found his father.

For Oxelson, DNA made the difference as well, linking him to a person who turned out to be a half-niece and whose grandmother proved to be his mother.

Both men returned to Vietnam where they met with various relatives – nieces and nephews, aunts and uncles, siblings, and in Oxelson’s case, his mother. As Oxelson put it, ultimately the reunion gave him the sense that “I’ve climbed the mountaintop. To me, that’s what it felt like – one of those monumental, lifetime achievements.”

Cornwall has continued to build his relationship with his birth family, and Oxelson has gone on to search for his father, eventually following the clues to Orangeburg, South Carolina.

“We’re close,” he says. “In fact, the genealogist believes that she has identified my grandmother or great-grandmother.” And while he admits that there is always the possibility of another dead end, he is optimistic and undeterred. “I guess one’s search for identity could last a lifetime.”

An ‘unscripted journey’

That genealogist is Trista Goldberg, who has helped countless adoptees in their quest for family and heritage.

“It’s been 50 years. It’s kind of crazy,” says Goldberg. “Something I think is important – and you don’t realise this until you get a little bit older in life – is that your roots are really important whether you’re adopted or not.”

Born in 1970 to an American serviceman and Vietnamese mother, she successfully found her mother in 2002, learning much through the process about the practical and emotional challenges it entailed. “After my own search I thought other adoptees could use assistance.”

Goldberg was aided in her search by a unique link to her mother’s native country. Before being sent abroad at the age of four, she had lived with a Vietnamese foster family, the father of which had left a note among Goldberg’s things that was later discovered by her American adoptive mother. The two families corresponded throughout the war, then when her foster family escaped Vietnam to Guam with the wave of “Boat People” – a mass exodus of some 800,000 Vietnamese refugees who fled the country by sea, often at great peril – her adoptive family sponsored their visa to resettle in the US.

“So I grew up with my Vietnamese foster family and was exposed to a lot of Vietnamese culture that most adoptees are not,” Goldberg explains. “I grew up with the customs. I was able to celebrate the holidays of Tet. So when I came back to Vietnam, it wasn’t a mystery. I already had it in my blood.”

What’s more, her foster father still had a brother in Vietnam who was able to help in the search for her birth mother. Through this connection and the assistance of her private investigator adoptive father, Goldberg discovered that her Vietnamese family had relocated to the US in 1991, and thanks to a nascent tool called the internet, she managed to track down a brother living in the state of Kansas in 2000.

Goldberg became adept at searching the internet and “making phone calls to random Vietnamese people with lots of I’ll call you back because I couldn’t understand the language”. Her search efforts were to be further honed with the introduction of DNA testing, which led to her partnership with the genetic ancestry company FamilyTreeDNA. “We were actually the beta group for the autosomal DNA [a form of DNA testing that can establish parentage], which is everywhere now.”

Since then, she has helped countless adoptees reconnect with their birth families.

“I don’t do the work for them,” she says. “I just point them in the right direction. I think that’s a healthier way to approach your reunion because sometimes if you’re automatically thrown into a reunion without actually struggling through the process, you miss some of the beauty in it. I commend their courage, because it’s a really unscripted journey to take.”

Now, to mark 50 years since Operation Babylift and the war’s end, Goldberg, Oxelson, Cornwall, and dozens of other adoptees are celebrating by attending a string of events in the US and Vietnam.

“It really was a humanitarian mission,” Oxelson asserts when asked about the criticisms that have been levelled at Operation Babylift over the decades. “You could probably find a political bent to plant your flag on for this, but when you’re on the ground in the middle of something like that, it’s a different thing. I think your basic humanity comes out.

“The bottom line is the people I know that I’ve met over the years who were a part of this effort were just decent human beings wanting to do the best they can.”