He rode to power in 2015 on a promise to respect the rule of law, but Muhammadu Buhari’s tenure as the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria ends on May 29 after eight years of disobeying a number of court orders, a clamp down on innocent Nigerian youths, and repeated attacks on the press.

During his formal declaration for presidency in 2014, Buhari vowed to respect the constitutional separation of powers between the executive, legislatures, and judiciary and respect the rights of citizens. Hoping that the promise would be fulfilled, the majority of Nigerian voters elected Buhari of the All Progressives Congress (APC) as president in preference to the incumbent, Goodluck Jonathan.

Speaking at the inauguration for his first four-year term on May 29, 2015, he said “the federal executive under my watch will not seek to encroach on the duties and functions of the legislative and judicial arms of government. The law enforcing authorities will be charged to operate within the Constitution.”

He repeatedly pledged that his administration would focus on guaranteeing press freedom and upholding the rule of law at different gatherings. He was re-elected on Feb. 23, 2019 and after receiving a certificate of return, Buhari said “the hard work to deliver a better Nigeria continues, building on the foundations of peace, rule of law and opportunities for all.”

Now that he has completed his eight years tenure as president, how did Buhari perform in terms of fulfilling his promises to respect the rule of law, and promote equity and freedom of the press?

Press attacks

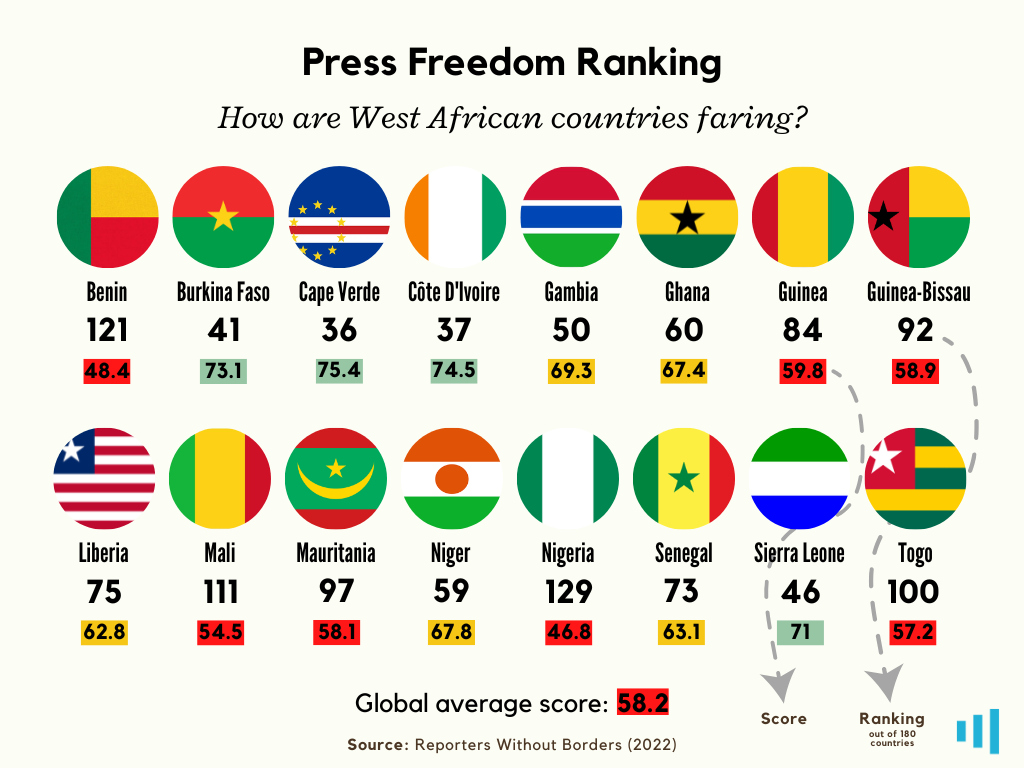

The press faced several attacks during Buhari’s administration despite the provision of the Constitution that mandates journalists to hold power to account. Since the controversial Cybercrime Act became law in 2015, many media outlets and journalists have witnessed attacks from authorities for doing critical journalism.

For instance, publisher and editor-in-chief of Weekly Source Newspaper in Bayelsa, Jones Abiri was arrested in 2016 by the State Security Service (SSS) for alleged links to armed militancy in the Niger Delta. He was not released until two years later.

Abiri was re-arrested in March 2019 and spent another seven months in prison before being granted bail by the Federal High Court in Abuja, after an intense campaign by media rights activists.

In 2018, police arrested Azeezat Adedigba, a reporter at Premium Times, to track her colleague, Samuel Ogundipe. The latter was in detention for five days over allegations that he had classified documents capable of causing a breach of national security and a breakdown of law and order.

For using his Facebook account to call out the federal government on the poor state of the nation, SSS arrested Ibrahim Dan-Halilu, a former editor with Daily Trust, in Aug. 2019. He was detained in Kaduna for 11 days without access to his relatives.

HumAngle also reports how Nigeria has invested heavily in the acquisition of surveillance equipment for its security agencies. In fact, Nigeria’s Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA) has since 2015 acquired equipment to spy on phone conversations and oftentimes, journalists are targeted with this technology.

Even during the last elections conducted by the administration, journalists were harassed and arrested while carrying out their duties.

Parade of suspects

Despite the provisions of the law, illegal parade of suspects by security operatives continued under Buhari’s administration and the uninformed public even saw it as legal.

Some lawyers who spoke with HumAngle said parading of suspects contravenes section 36 of Nigeria’s 1999 constitution, which guarantees the presumption of innocence of suspects until proven guilty by a competent court of law. But the police continue to do this with the argument that it helps to update the citizens about their fight against insecurity.

A lawyer, Tunde Adeoye, told HumAngle that by parading suspects, security operatives violate the right to a presumption of innocence, and the right to privacy. Such action means if they are vindicated and released by a court, their lives will still be affected, he said.

HumAngle understands that suspects also continued to face a series of media trials with “cross-examination” by law enforcement officials at crowded press conferences. Sometimes, journalists interrogate the suspects with a view to confirming their involvement in the criminal offences levelled against them.

One popular case in recent times was the parade of Chidinma Ojukwu, the suspect in the death of SuperTV Chief Executive Officer, Osifo Ataga. The 21-year-old undergraduate was paraded by the Lagos State Police command before journalists and compelled to give an account of how she committed the alleged crime.

Also, the officials of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) have become notorious for clamping down on Nigerian youths as they subject them to public shame through media parades in their hunt for internet fraudsters. Their names and pictures are spread on social media, before a trial has convicted them.

All of these things happened in Nigeria before Buhari’s term as president, but his government has done little to stop it.

Extrajudicial killings

Section 33 (1) of the 1999 Constitution guarantees the right to life for all Nigerians but the manner security agencies, including the army, are deployed to suppress civil liberties was not different from what was obtainable during the military era.

In Dec. 2015, the Nigerian Army launched an attack on members of the country’s Shia community, killing hundreds of people. Today, many families still carry the scars. The military claimed that the Shia Muslims attempted to assassinate former Chief of Army Staff Tukur Buratai when the incidents occurred but multiple sources who spoke with HumAngle, however, insisted the soldiers killed scores without any threat to Buratai’s safety.

The IMN members were planning to celebrate the first day of Rabi’ al-Awwal when the soldiers arrived at the venue of their programme. As the arguments between the soldiers and the IMN members got intense, the soldiers reportedly opened fire on the people, killing scores. They later proceeded to the residence of El-Zakzaky, where hundreds of people were hiding.

According to Amnesty International, the incident led to the death of hundreds of people and many were allegedly buried secretly by the army in a mass grave and 23 families were said to have been wiped out of existence.

In Oct. 2020, soldiers in another case of gross human rights violations inflicted a war-grade assault on the Oyigbo community in Rivers state, after mobs suspected to be members of Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) killed some security personnel.

While the military authorities claimed that troops were deployed to the town to fish out terrorists who murdered soldiers and police officers, on-the-ground investigations revealed that soldiers inflicted bloodshed on the town.

HumAngle also reported how soldiers sent on a peacekeeping assignment to Cross River communities fighting over a parcel of land at the boundary for nearly a century became murderous in Aug. 2022.

Though the International Humanitarian Law, to which Nigeria is a party, provides that the military must take precautions to minimise harm to civilians during armed conflict, soldiers deployed to Nko used extreme force on residents.

Clampdown on peaceful protesters

The Nigerian Police have a history of brutality and disrespect for the rule of law. For years, its officers have been accused of disregarding the human rights of accused persons, violently suppressing protests, infringing on fundamental rights, and corruption.

All of these led to the #EndSARS protests against the activities of the operatives of the police’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). For weeks in Oct. 2020, many Nigerian youths protested against all forms of irregularities by the police unit. The protests led to the disbandment of the police tactical squad.

But soldiers were deployed to the epicentre of the nationwide protests at Lekki Tollgate on Oct. 20, 2020, killing a number, how many is still not confirmed. Many innocent Nigerians were also arrested randomly after the incident.

Aside from this, security forces used excessive unnecessary force, including lethal force, against peaceful demonstrators on different occasions, a development that grossly negates the core democratic tenets of freedom of assembly, association, and expression.

“It was painful that #RevolutionNow protesters, June 12 protesters, Yoruba Nation agitators, and many other groups were criminalised by security operatives who under Buhari did not see protests as an essential element of democracy,” Kemi Afolabi, a concerned Nigerian brutalised during a protest in 2021 told HumAngle.

Disobedience of court orders

HumAngle recalls that there was also a pattern of failure to comply with court judgements under Buhari’s administration. This, according to human rights lawyers, was a mockery of the law.

Under his watch, the SSS became notorious for disobeying court orders and he did not at any point publicly condemn the security operatives for disobeying the courts.

To mention but a few, Sambo Dasuki, ex-Nigerian military officer who served as National Security Adviser to President Goodluck Jonathan was arrested in Dec. 2015 over allegations that he diverted $2.1 billion arms purchase deal. The courts granted Dasuki bail five times but never released until four years later.

It was a similar situation in the case of Omoyele Sowore, an online publisher arrested in 2019 over allegations that he wanted to overthrow Buhari. Despite a court order that freed him on bail, he was not released until he spent 134 days in detention. Even in broad daylight, SSS invaded the court to re-arrest him after he had been granted bail.

Festus Ogun, a lawyer, says disobedience of court orders weakens judicial authority and endangers democracy.

“When court orders are not respected, the last hope of the common man becomes the lost hope of the common man.”

Buhari claimed to be a “converted democrat” but his administration’s abuse of human rights shows otherwise.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.