TORONTO — Tyler Glasnow threw seven, maybe eight, pitches in the bullpen. There was no more time to wait. The red emergency light was flashing.

For 14 years, Glasnow has made a nice living as a pitcher. He has thrown hard, if not always durably or effectively.

There is one thing he had not done. In 320 games, from the minors to the majors, from the Arizona Fall League to the World Series, he never had earned a save.

Until Friday, that is, and only after the Dodgers presented him with this opportunity out of equal parts confidence and desperation: Please save us. The winning run is at the plate with no one out. If you fail, we lose the World Series.

No pressure, kid.

He is not one of the more intense personalities on the roster, which makes him a good fit in a situation in which someone else might think twice, or more, at the magnitude of the moment.

“I honestly didn’t have time to think about it,” Glasnow said.

In Game 6 on Friday, the Dodgers in order used a starter to start, a reliever to relieve, the closer of the moment, and then Glasnow to close. In Game 7 on Saturday, the Dodgers plan to start Shohei Ohtani, likely followed by a parade of starters.

Glasnow, who said he could not recall ever pitching on back-to-back days, could be one of them.

“I threw three pitches,” he said. “I’m ready to go.”

The Dodgers had asked him to be ready to go in relief on Friday, so he moseyed on down to the bullpen in the second inning. He didn’t really believe he would pitch. After all, Dodgers starter Yoshinobu Yamamoto had thrown consecutive complete games. If Yamamoto could not throw another, Glasnow did not believe he would be the first guy called.

He was not. Justin Wrobleski was, protecting a 3-1 lead, and he delivered a scoreless seventh inning. Closer Roki Sasaki was next, and the Dodgers planned for him to work the eighth and ninth.

Glasnow said bullpen coach Josh Bard warned him to be on alert. Sasaki walked two in the eighth but escaped. He hit a batter and gave up a double to lead off the ninth, and the Dodgers rushed in Glasnow.

“I warmed up very little, got out there,” Glasnow said. “It was like no thinking at all.”

The Dodgers’ scouting reports gave Glasnow and catcher Will Smith reason to believe Ernie Clement would try to jump on the first pitch, so Glasnow said he threw a two-seam fastball that he seldom throws to right-handed batters. Clement popped up.

The next batter, Andrés Giménez, hit a sinking fly ball to left fielder Kiké Hernández. Off the bat, Glasnow said he feared a hit.

If the ball falls in, Giménez has a single and the Dodgers’ lead shrinks to one run. If the ball skips past Hernández, the Blue Jays tie the score.

Glasnow said he had three brief thoughts, in order:

1: “Please don’t be a hit.”

Hernández charged hard and made the running catch.

2: “Sweet, it’s not a hit.”

Hernández threw to second base for the game-ending double play.

3: “Nice, a double play.”

Wrobleski tipped his cap to his new bullpen mate.

“He’s a beast, man,” Wrobleski said. “To be able to come in in that spot, it takes a lot of mental strength and toughness. He did it. I didn’t expect anything less out of him, but it was awesome.”

Wrobleski was pretty good himself. The Dodgers optioned him the maximum five times last year and four times this year. He did not pitch in the first three rounds of the playoffs, and his previous two World Series appearances came in a mop-up role and during an 18-inning game.

Dodgers reliever Justin Wrobleski reacts after striking out Toronto’s Andrés Giménez to end the seventh inning in Game 6 of the World Series on Friday.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

On Friday, they entrusted him with helping to keep their season alive. They got three critical outs from Wrobleski, who is not even making $1 million this season, and three more from Glasnow, who is making $30 million.

“We got a lot of guys that aren’t making what everybody thinks they’re making, especially down in that bullpen,” Wrobleski said. ”We were talking about it the other day. There’s a spot for everybody. If you keep grinding, you can wedge yourself in.”

He did. He was recruited by Clemson out of high school, then basically cut from the team.

“They told me to leave,” he said.

Did a new coach come in?

“No, I was just bad,” he said. “I had like a 10.3 ERA.”

Glasnow signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates out of Hart High in Santa Clarita. In the majors, the Pirates tried him in relief without offering him a chance to close. Did they fail to recognize a budding bullpen star? “I never threw strikes,” he said. “I just wasn’t that good.”

We’ve all heard stories about the kid who goes into his backyard with a wiffle ball, taking a swing and pretending to be the batter who hits the home run in the World Series.

Glasnow doesn’t hit.

“I’ve had all sorts of daydreams about every pitching thing possible as a kid — relieving, closing out a game, starting in the World Series,” he said. “I thought about it all the time. So it’s pretty wild. I haven’t really processed it, either. I think going out to be able to get a save in the World Series is pretty wild.”

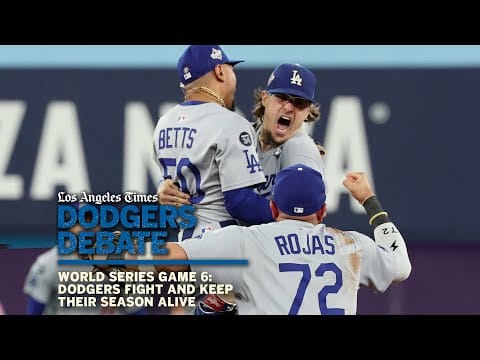

The game-ending double play was reviewed by instant replay, so Glasnow missed out on the trademark closer experience: the last out, immediately followed by the handshake line. Instead, everyone looked to the giant video board and waited.

Eventually, an informal line formed.

“I got some dap-ups,” he said. He smiled broadly, then walked out into the Toronto night, the proud owner of his first professional save. For his team, and for Los Angeles, he had kept the hope of a parade alive.