‘littleboy/littleman’ review: An immigrant story as freestyle jazz

An immigrant drama by Rudi Goblen about two brothers born in Nicaragua, “littleboy/littleman,” now receiving its world premiere at the Geffen Playhouse, is an American story at its core.

Lest we forget our past, America is the great democratic experiment precisely because it’s a land of immigrants. Out of many, one — as our national motto, E pluribus unum, has it. How have we lost sight of this basic tenet of high school social studies?

Our tendency to ghettoize drama — along racial or immigrant lines — reflects the failure to understand our collective story.

Goblen, who (like a.k. payne, author of “Furlough’s Paradise”) was a playwriting student of Geffen Playhouse artistic director Tarell Alvin McCraney at Yale, has created not a conventionally worked out two-hander, but an intuitively structured performance piece. Infused by live music and inflected with hip-hop style poetry, “littleboy/littleman” crashes through the fourth wall to make direct contact with theatergoers, who are seated on three sides of the playing area and always just a high-five away.

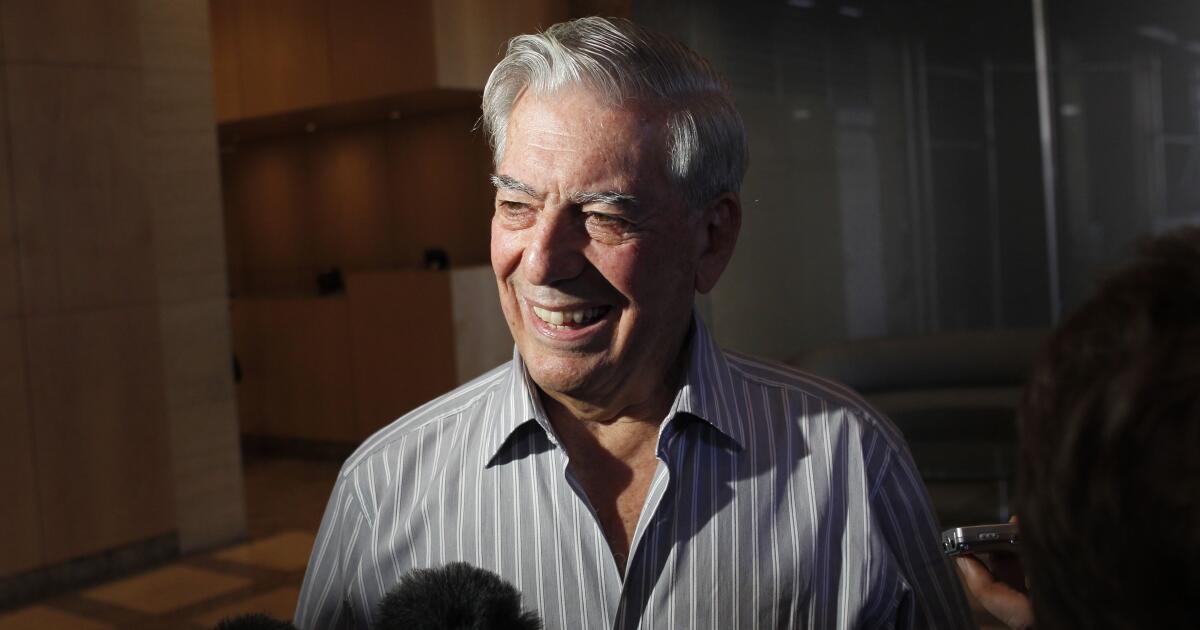

Marlon Alexander Vargas, the dynamic, sweet-faced performer who plays Fito Palomino, the more creative and mercurial of the two brothers, is on stage interacting with the audience before the play begins. As the musicians — music director Dee Simone on drums and Tonya Sweets on bass — warm up the crowd from their platform at the back of the playing area, Vargas, ever-in-motion, greets theatergoers and counts down to the start of the show.

Rules are spelled out at the top that make clear that this isn’t one of those docile theatergoing experiences, in which the audience is expected to keep mum as the actors do all the work. Spectators are encouraged to make some noise — to show love when they want to show love and to show it even when they don’t.

These friendly instructions are impishly delivered by Vargas, whose performance outside the play has an effect on our experience of his character inside the play. The fate of Fito is the emotional crux of the drama, and what happens to him matters all the more to us because of our theatrical connection to Vargas, our de facto host and impromptu buddy.

Goblen sets up a drama of fraternal contrasts. Bastian Monteyero (Alex Hernandez), the older and more straitlaced of the two brothers, has a tough, no-nonsense demeanor that’s all about discipline and conformity. He’s a bit of a recluse, but he plays by the rules and demands the same from Fito.

A street performer, Fito dreams of opening a vegan restaurant that will offer his community access to affordable, healthful meals. This idea seems far-fetched to Bastian, and he tells Fito that if he wants to continue living with him, he’s going to have to get a real job.

Bastian hooks Fito up with a friend who’s employed at a cleaning service. But scrubbing public toilets isn’t Fito’s idea of an alternative course. Bastian wants his brother off the streets. There are dangers afoot in Sweetwater, Fla., far worse than unpleasant paid work.

A law officer in town, a sadist who demands complete subservience, has it in for Fito, who describes this menacing figure as “a gangster with a badge.” He also calls him “brown on the outside, white on the inside,” and bemoans to his brother the Latino infighting (“the worst thing they ever did was give us all flags”) that only divides people who have political reason to be in solidarity.

Bastian, who affects a white-sounding Midwestern voice when he hustles donations in his telemarketing job, can’t help taking the latter comment personally. He’s made no secret that he wants to change his name so his resume won’t be ignored when he applies for management jobs.

The two brothers have different fathers, and Fito doesn’t have the option of passing. In any case, he’s more embracing of his identity as a person of color than Bastian. What both of them have in common is that they survived both their harrowing childhoods in Nicaragua and their unrelentingly challenging journeys in America, having been raised by a single mother, whose death still haunts them.

Bastian and Fito love each other, but don’t always like each other. Hernandez’s Bastian is a formidable presence, angry, strict and domineering — the qualities he’s needed to navigate a bureaucratic system that has little concern for the feelings of immigrant outsiders. Vargas’ Fito, by contrast, has his head in the clouds and his heart on his sleeve. Goblen never loses sight of their affection even as their conflict grows louder and more bruising.

Bassist Tonya Sweets, from left, Marlon Alexander Vargas and drummer Dee Simone in “littleboy/littleman” at Geffen Playhouse.

(Jeff Lorch)

“littleboy/littleman” is tricky in its theatrical rhythms. It’s like a piece of music that keeps switching harmonic structures, not wanting to get stuck in the same groove. Goblen’s manner of writing is closer to free jazz or freestyle hip-hop than traditional drama.

Director Nancy Medina’s staging, circumnavigating a theatrical circle, lifts the audience out of its proscenium passivity into something almost immersive and definitely interactive. Tanya Orellana’s scenic design and Scott Bolman’s moody lighting create a performance space that is well suited to a work composed as a series of riffs. The influence of McCraney’s “The Brothers Size” is palpable not only in the thematic architecture of the play, but also in how the piece moves on stage.

The staccato nature of the writing is helped enormously by the entrancing acting of both Vargas, who breezes through different theatrical realms as though he had wings, and Hernandez, who locks realistically into character. It’s a credit to the play and to the performers that, by the end of “littleboy/littleman,” the differences between the two brothers seem less important than what they have in common.

Not all the dramatic elements are smoothly integrated, but the production ultimately finds a coherence, not so much in the music (composed by Goblen himself), but in the emotional truth of the brothers’ pressure-cooker lives. Vulnerability unites not only Bastian and Fito, but all of us witnessing their story who hope against hope that compassion will somehow win the day.

‘littleboy/littleman’

Where: Audrey Skirball Kenis Theater at Geffen Playhouse, 10886 Le Conte Ave., Los Angeles

When: 7:30 p.m. Wednesdays-Thursdays, 8 p.m. Fridays, 3 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 2 p.m. Sundays. Ends Nov. 2

Tickets: $45 – $109 (subject to change)

Contact: (310) 208-2028 or www.geffenplayhouse.org

Running time: 1 hour, 30 minutes (no intermission)