At the Mount Hagen Festival in Papua New Guinea, Janet met a community of people with a living connection to one of the darkest aspects of Papua New Guinea’s recent history – cannibalism

A dark tourist who has travelled to the furthest corners of the Earth met a tribe with a cannibal past at one of the “craziest, weirdest” events she has ever been to.

In recent years, Janet Newenham has really been clocking up the miles. The 38-year-old from Cork leads groups of women to strange and largely inaccessible places, including the alien-treed Socotra Island off the coast of Yemen and the ultra-advanced Chinese city of Chongqing.

However, few places could prepare her for the Mount Hagen Festival in Papua New Guinea, where hundreds of tribes from all over the island come together to showcase their traditional clothing, dances and games. It is a riot of colour and movement, unlike anything else in the world.

There, Janet met a community of people with a living connection to one of the darkest aspects of Papua New Guinea’s recent history – cannibalism.

By all accounts, the practice no longer occurs in the country, with the last well-documented incidents taking place in the 1960s. One of the last reported cases unfolded in the malaria-infested swampland of Sepik, a 45-minute plane ride from the city of Mount Hagen.

Have you got a story to share? Email [email protected]

READ MORE: Family banned from boarding British Airways flight over marks on baby son’s leg

It “was in 1964 when a group of men raided a neighbouring village for meat – as their ancestors had for thousands of years. All seven offenders were hanged by ‘kiaps’ – Australian patrol officers who were the law of the land until PNG’s independence in 1975,” wrote Ian Neubauer in 2018 following a visit to the region.

One tribe that also partook in cannibalism in the same decade is the Asaro people, who are known as the Asaro Mud Tribe.

“If people did them wrong or tried to steal their animals, often they would kill a member of the opposite tribe as punishment,” Janet told the Mirror following her visit. “They stopped more than 50 years ago. They said all tribes stopped in the 1960s.

“We did also meet other tribes that touched on it. And explained it was only ever to honour their family or to exact revenge on another tribe if they had killed someone.”

The timeline means that there are a handful of older members of the Asaro living today who were involved. “It wasn’t scary (to meet them), but the more you think about it, it is crazy to think that they have eaten people,” Janet added.

The reputation of the Asaro stretches far beyond the borders of Papua New Guinea, and not just because of their unusual past. Their cultural dress has also caught the eye and inspired many copycats. “They are covered in mud and they wear these really heavy masks designed to scare away their enemies,” Janet explained.

The history of the look is mired in confusion, but it is unlikely to be as ancient as one might suspect. In fact, some historians believe it had its origins in the 1950s.

Sign up to the Mirror Travel newsletter for a

You can get a selection of the most interesting, important and fun travel stories sent to your inbox every week by subscribing to the Mirror Travel newsletter. It’s completely free and takes minutes to do.

“According to one theory, some time ago, Asaro people were hiding from their enemies from another tribe near a riverbank of white clay. The Asaro got covered in clay and mud, and their appearance frightened the opponents, as in the traditions of the tribes, only the ghost can be white. But the legends of the Asaro people still do not explain why this tradition became so important for them, or how they got bamboo claws on their fingers,” writes the Journal News.

“Another version says that once, during a wedding of one Asaro, one man came in a strange costume with a terrible mask and clay on his body. Everyone thought he was a ghost, so they fled.”

According to research conducted in September 1996 by Danish anthropologist Ton Otto from Aarhus University, the Mudmen tradition is an invention of the Asaro people. Its current elaborate form evolved from a 1957 cultural fair, when the Asaro debuted the look, Otto claims.

Over the years, the tribe has used events such as Mount Hagen to show off and perfect their costumes and dances. However, this has given others the chance to copy the striking get-up.

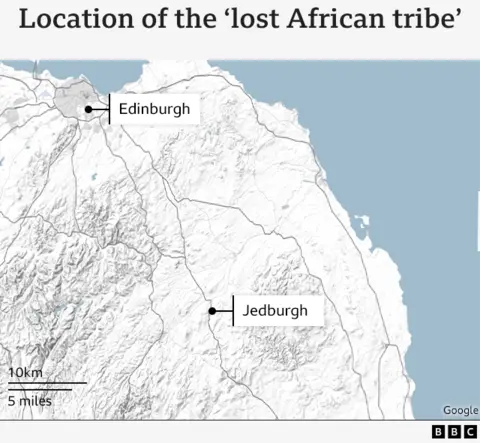

Recently 29-year-old subsistence farmer Kori from Komunive village told the BBC of his concerns over plagiarism.

“The government does not recognise or protect our ownership rights and everyone in the highlands is now claiming to be a mud man,” he says. “But it’s our story and the others have copied it from us. It is a big worry for us because we don’t have any copyright protection.”

James Dorsey visited the Asaro five years ago and heard how an older member of the tribe relocated to a different part of the highlands in the late 20th century, which brought him into contact with other groups. From them, he learned the practice of bakime: using a disguise to take revenge on an enemy.

The returning elder introduced the method of covering one’s face with white tree sap as a disguise. This then morphed into girituwai, whereby a light wooden frame with a mud-soaked bag covering it engulfs the entire head. These were a part of the inter-tribe “spearing raids to capture pigs and women” that were common until the mid-20th century, Geographic Expeditions reports.

“In an effort to curb this cultural violence, in 1957 local organizers put on what was called the “First Eastern Highlands Agricultural Show,” and they invited the Asaro to participate. The tribal chairman at that time, Ruipo Okoroho, saw an opportunity to put the Mud Men on the tourist map. Organizing all of the local headmen, he had them wear, for the first time, the prototypes of today’s Papua New Guinea masks, large, surreal, and weighty,” the publication continues.

“The story goes that the day of the first Sing-Sing, as the show is popularly called, over 200 masked Mud Men stalked slowly onto the grounds, driving a screaming and terrified audience before them. No one had seen anything like them, especially not in such numbers. The Mud Men took first prize for tribal representation that year and the following two years, prompting an end to all such competitions in the future.”