Senior politicians discuss the Democratic Party youth movement

Barbara Boxer decided she was done. Entering her 70s, fresh off reelection to the U.S. Senate, she determined her fourth term would be her last.

“I just felt it was time,” Boxer said. “I wanted to do other things.”

Besides, she knew the Democratic bench was amply stocked with many bright prospects, including California’s then-attorney general, Kamala Harris, who succeeded Boxer in Washington en route to her selection as Joe Biden’s vice president.

When Boxer retired in 2017, after serving 24 years in the Senate, she walked away from one of the most powerful and privileged positions in American politics, a job many have clung to until their last, rattling breath.

(Boxer tried to gently nudge her fellow Democrat and former Senate colleague, Dianne Feinstein, whose mental and physical decline were widely chronicled during her final, difficult years in office. Ignoring calls to step aside, Feinstein died at age 90, hours after voting on a procedural matter on the Senate floor.)

Now an effort is underway among Democrats, from Hawaii to Massachusetts, to force other senior lawmakers to yield, as Boxer did, to a new and younger generation of leaders. The movement is driven by the usual roiling ambition, along with revulsion at Donald Trump and the existential angst that visits a political party every time it loses a dispiriting election like the one Democrats faced in 2024.

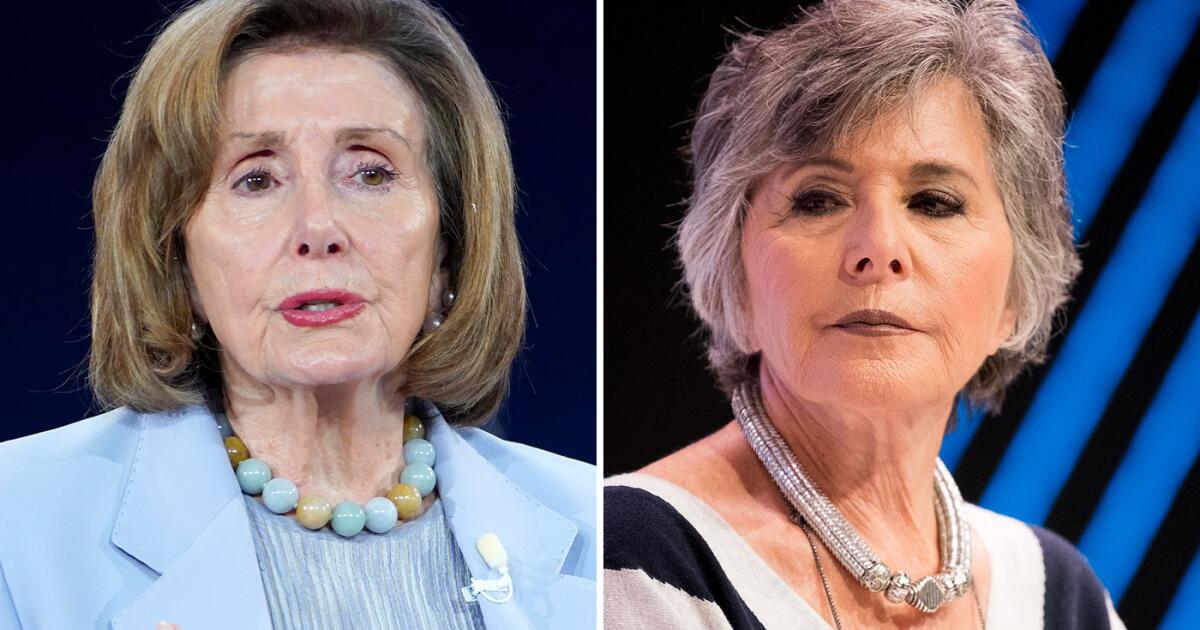

Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has become the highest profile target.

Last week, she drew a second significant challenger to her reelection, state Sen. Scott Wiener, who jumped into the contest alongside tech millionaire Saikat Chakrabarti, who’s been campaigning against the incumbent for the better part of a year.

Pelosi — who is 85 and hasn’t faced a serious election fight in San Francisco since Ronald Reagan was in the White House — is expected to announce sometime after California’s Nov. 4 special election whether she’ll run again in 2026.

Boxer, who turns 85 next month, offered no counsel to Pelosi, though she pushed back against the notion that age necessarily equates with infirmity, or political obsolescence. She pointed to Ted Kennedy and John McCain, two of the senators she served with, who remained vital and influential in Congress well into their 70s.

On the other hand, Boxer said, “Some people don’t deserve to be there for five minutes, let alone five years … They’re 50. Does that make it good? No. There are people who are old and out of ideas at 60.”

There is, Boxer said, “no one-size-fits-all” measure of when a lawmaker has passed his or her expiration date. Better, she suggested, for voters to look at what’s motivating someone to stay in office. Are they driven by purpose — and still capable of doing the job — “or is it a personal ego thing or psychological thing?”

“My last six years were my most prolific,” said Boxer, who opposes both term limits and a mandatory retirement age for members of Congress. “And if they’d said 65 and out, I wouldn’t have been there.”

Art Agnos didn’t choose to leave office.

He was 53 — in the blush of youth, compared to some of today’s Democratic elders — when he lost his reelection bid after a single term as San Francisco mayor.

“I was in the middle of my prime, which is why I ran for reelection,” he said. “And, frankly,” he added with a laugh, “I still feel like I’m in my prime at 87.”

A friend and longtime Pelosi ally, Agnos bristled at the ageism he sees aimed at lawmakers of a certain vintage. Why, he asked, is that acceptable in politics when it’s deplored in just about every other field of endeavor?

“What profession do we say we want bright young people who have never done this before to take over because they’re bright, young and say the right things?” Agnos asked rhetorically. “Would you go and say, ‘Let me find a brain surgeon who’s never done this before, but he’s bright and young and has great promise.’ We don’t do that. Do we?

“Give me somebody who’s got experience, “ Agnos said, “who’s been through this and knows how to handle a crisis, or a particular issue.”

Pete Wilson also left office sooner than he would have like, but that’s because term limits pushed him out after eight years as California governor. (Before that, he served eight years in the Senate and 11 as San Diego mayor.)

“I thought that I had done a good job … and a number of people said, ‘Gee, it’s a pity that you can’t run for a third term,’ ” Wilson said as he headed to New Haven, Conn., for his college reunion, Yale class of ’55. “As a matter of fact, I agreed with them.”

Still, unlike Boxer, Wilson supports term limits, as a way to infuse fresh blood into the political system and prevent too many over-the-hill incumbents from heedlessly overstaying their time in office.

Not that he’s blind to the impetus to hang on. The power. The perks. And, perhaps above all, the desire to get things done.

At age 92, Wilson maintains an active law practice in Century City and didn’t hesitate — “Yes!” he exclaimed — when asked if he considered himself capable of serving today as governor, even as he wends his way through a tenth decade on Earth.

His wife, Gayle, could be heard chuckling in the background.

“She’s laughing,” Wilson said dryly, “because she knows she’s not in any danger of my doing so.”