What to know about Chuck’s Arcade, the adult-focused Chuck E. Cheese

Chuck E. Cheese is all grown-up. Sort of.

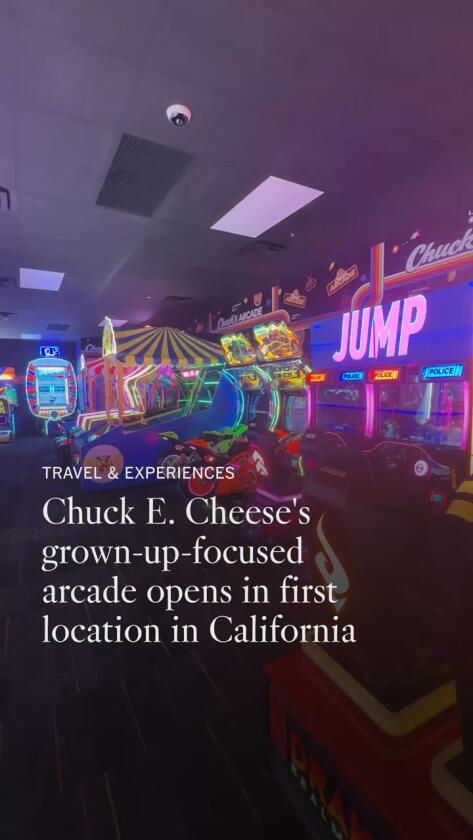

Brea Mall is now home to a Chuck’s Arcade, the first location in California and 10th in the U.S. When the company unveiled the concept earlier this year, headlines branded it as an “adult” Chuck E. Cheese. There’s some truth in that, but it’s not the full story.

Combine the word “adult” and “arcade” and recognizable spaces — say, Dave & Buster’s — instantly come to mind. Here in SoCal, we also have Two Bit Circus in Santa Monica, which marries retro and modern games with beer and cocktails. Chuck’s Arcade isn’t all that similar to either.

Chuck’s Arcade has a merchandise booth with vintage looks.

(Gabriella Angotti-Jones / For The Times)

But we were intrigued by its promise of retro gaming and its attempts to appeal to a less kid-focused audience. You won’t, for instance, encounter a pizza party full of 7-year-olds here.

So what will you find? And will it possess the vintage arcade vibes many of us are craving? With the company and its mouse mascot now a cool 48 years old, we weren’t sure what to expect. So we took a visit to Chuck’s Arcade seeking answers.

-

Share via

Where an adult can be a ‘kidult’

It’s not surprising to encounter a grown-up with fond memories of Chuck E. Cheese. For me, I was hooked by the stilted-yet-charming robotic performances from their once ubiquitous animatronic bands, in which tunes were delivered amid the clickety-clack of machinery. Yet a Chuck E. Cheese today is a fully-realized kid-focused video-game-inspired rec room, one where digital floors encourage a more active form of play. David McKillips, president and chief executive of the company, says the firm’s core locations heavily target those between the ages of 3 and 8.

And thus, Chuck’s Aracade, says McKillips, will fill a void. He’s hoping it taps into the marketing segment known as the “kidult” — grown-ups, perhaps, who were raised on games and still cherish the thought of crowding around a “Ms. Pac-Man” console. The kidult sector is booming, encompassing everyone from the so-called “Disney adult” to those who carry a Labubu doll as a fashion accessory. Think anyone who believes that a childlike openness to play and silliness doesn’t have to be eradicated by maturity.

David McKillips, president and chief executive of Chuck E. Cheese, poses for a portrait with a retired Mr. Munch figure.

(Gabriella Angotti-Jones / For The Times)

So how does Chuck’s Arcade plan to reach the kidult? Its 3,600-square-foot space boasts 70 games, including a small — emphasis on small — retro section where one will find coin-op cabinets of “Tron,” “Centipede,” “Mortal Kombat” and a “Ms. Pac-Man” head-to-head arcade table. And while a modern Chuck E. Cheese is school-cafeteria bright, Chuck’s Arcade is dark, its black walls and low lighting recalling the arcades of the ’80s and ’90s.

McKillips says Chuck’s Arcade “is appealing to the collectible market,” betting large on grown-ups being drawn to its plethora of claw machines. There are also prize apparatuses dedicated largely to Funko’s plastic figurines.

It’s near the mall food court — which is part of the business strategy

The Chuck E. Cheese company has long had it eye on the Brea Mall.

In an era when malls are being refocused to cater to a more experience-based economy — see, for instance, the escape rooms of Westfield Century City, or Meow Wolf eventually taking over a portion of what is currently the Cinemark complex at Howard Hughes L.A. — Chuck E. Cheese saw an opportunity in Orange County.

One game at Chuck’s Arcade may drop Chuck E. Cheese plushies.

(Gabriella Angotti-Jones / For The Times)

“We’ve been trying to get in here for a year and a half,” says McKillips. “The foot traffic is phenomenal. The anchors are strong. They have a really solid food court.”

The food court was a massive selling point.

“That’s where teens are congregating,” he says. “That’s where parents and kids are together. They’ll have a bite to eat and come over and play some games.”

There’s no booze … or even pizza

Here’s one way to think about Chuck’s Arcade: Imagine a Chuck E. Cheese, but subtract the pizza and detract the drinks. In one corner of Chuck’s Arcade rests a giant Skittles machine, and there is more candy available at the front counter. But the company decided to go without a proper food and beverage program for Chuck’s Arcade, meaning those grown-up kidults won’t be sipping on booze or mocktails.

I told McKillips I was surprised. At home, I’m more than 40 hours into “Donkey Kong Bananza,” but I wind down by playing the game and enjoying a beer — one of the core benefits, I believe, of being a certified kidult.

McKillips argues this is actually an advantage for Chuck’s Arcade, allowing it to reach a grown-up audience but still feel family-friendly. Just one Chuck’s Arcade, he says, is equipped to serve beer, wings and pizza, and it’s in Kansas City, Mo.

“This is an arcade destination,” he adds. “We’re not hosting birthday parties. We don’t do [food & beverage] here. You’re going to come here and play games.”

Where’s the nostalgia?

Chuck’s Arcade staffer Sabrina Hernadez checks out games at the new Brea location hours before it opens it doors.

(Gabriella Angotti-Jones / For The Times)

I should be the audience for Chuck’s Arcade. I have fond memories of the brand.

Chuck E. Cheese, the character and the pizza chain, was the brainchild of Nolan Bushnell, best known as the founder of Atari. The franchise launched in 1977 in San José, first branded as Chuck E. Cheese Pizza Time Theatre. As Chuck E. Cheese flourished throughout the early ’80s, the original animatronic figures were a bit more bawdy (Chuck was a smoker). Bushnell envisioned the initial Chuck E. Cheese robotic characters as entertainment that appealed to the grown-ups while the kids played games in the neighboring room.

When I first heard of Chuck’s Arcade, I hoped the company was getting back a bit to its roots. And there’s a nostalgic touch here and there. Aside from the aforementioned selection of vintage games, there’s also a Mr. Munch figurine, who is displayed in a clear case and does not turn on. Munch, a friendly, purple-ish hairball of a creature, was once the anchor of Chuck E. Cheese’s Make Believe Band.

Seeing that one figure treated as a museum piece felt like a half-hearted wave to fans who grew up with Chuck. And while claw gizmos and plastic figurines aren’t my thing, I understand their popularity and wouldn’t mind their presence if there was a greater supply of old-school games, and perhaps some pinball machines.

With a digital key card for Chuck’s Arcade starting at $10, the buy-in to try out the space isn’t large, but this felt like a tentative step into adulthood. After all, Chuck is well beyond drinking age. The mouse deserves a cocktail.