Watchdogs say new L.A. County policy is an attempt to muzzle criticism

L.A. County’s watchdogs suddenly need to ask permission before barking to the press and public.

County oversight officials and civil rights advocates are raising concerns about a new policy they say improperly limits their rights to communicate — including with other members of local government.

The policy, enacted Sept. 11, requires oversight officials to send many types of communications to the Executive Office of the Board of Supervisors for approval.

The policy says “press releases, advisories, public statements, social media content, and any direct outreach to the BOS or their staff” must be “reviewed, approved and coordinated” before being released publicly or sent to other county officials.

The policy says the change “ensures that messaging aligns with County priorities, protects sensitive relationships, and maintains a unified public voice.”

Eric Miller, a member of the Sybil Brand Commission, which conducts inspections and oversight of L.A. County jails, said the policy is the latest example of the county “attempting to limit the oversight of the Sheriff’s Department.” He said he made the remarks as a private citizen because he was concerned the new communications policy barred him from speaking to the media in his role as an oversight official.

Michael Kapp, communications manager for the Executive Office of the Board of Supervisors, said in an email that he personally drafted the policy shortly after he started in his position in July and discovered there “was no existing communications guidance whatsoever for commissions and oversight bodies.”

“Without clear guidance,” he said, “commissions and oversight bodies – most of which do not have any communications staff – were developing their own ad hoc practices, which led to inconsistent messaging, risks of misinformation, and deeply uneven engagement with the Board, the media, and the public.”

Although it is increasingly common for government agencies to tightly restrict how employees communicate with the press and public, L.A. County oversight officials had enjoyed broad latitude to speak their minds. The watchdogs have been vocal about a range of issues, including so-called deputy gangs in the Sheriff’s Department and grim jail conditions.

Some questioned the timing of the policy, which comes after a recent run of negative headlines, scandals and hefty legal payouts to victims of violence and discrimination by law enforcement.

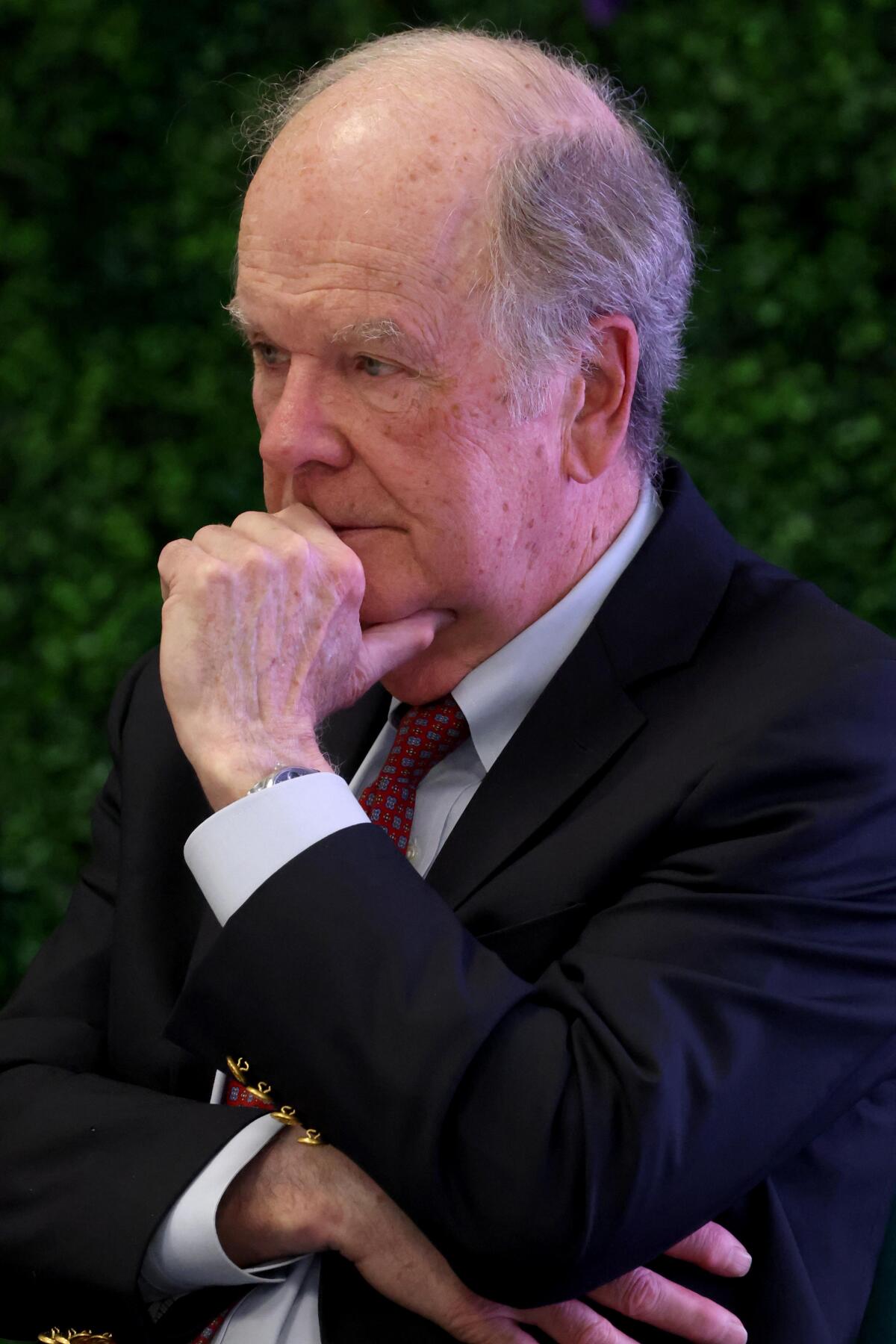

Long-time Los Angeles Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission Chair Robert C. Bonner presides over the commission‘s meeting at St. Anne’s Family Services in Los Angeles on June 26, 2025. Bonner says he has since been forced out of his position as chair.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Longtime Los Angeles Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission chair Robert Bonner said he was ousted this summer as he and his commission made a forceful push for more transparency.

In February, former commission Chair Sean Kennedy resigned after a dispute with county lawyers, stating at the time that it was “not appropriate for the County Counsel to control the COC’s independent oversight decisions.”

California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta announced this month that his office is suing L.A. County and the Sheriff’s Department over a “humanitarian crisis” that has contributed to a surge in jail deaths.

Kapp said the policy came about solely “to ensure stronger, more effective communication between oversight bodies, the public, and the Board of Supervisors.”

Peter Eliasberg, chief counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, called the policy “troubling” and said it appears to allow the county to tell “Sybil Brand you’ve got to tone it down, or telling COC this isn’t the message the board wants to put out.”

“I learn about this policy right around the same time the state attorney general sues the county over horrific conditions in the jails,” Eliasberg said.

“There’s a ton of stuff in that lawsuit about Sybil Brand and Sybil Brand reports,” he added, citing commission findings that exposed poor conditions and treatment inside county jails, including vermin and roach infestations, spoiled food and insufficient mental health treatment for inmates.

Some current and former oversight officials said the new policy leaves a number of unanswered questions — including what happens if they ignore it and continue to speak out.

Kapp, the Executive Office of the Board of Supervisors official who drafted the policy, said in his statement that “adherence is mandatory. That said, the goal is not punishment – it’s alignment and support.”

During the Civilian Oversight Commission’s meeting on Thursday, Hans Johnson, the commission’s chair, made fiery comments about the policy, calling it “reckless,” “ridiculous and ludicrous.”

The policy “represents one of the most caustic, corrosive and chilling efforts to squelch the voice of this commission, the office of inspector general and the Sybil Brand Commission,” Johnson said. “We will not be gagged.”

Times staff writer Sandra McDonald contributed to this report.