How the diamond engagement ring was invented – and sold around the world | Features

For decades, men in many countries were expected to spend two or even three months’ salary on a diamond engagement ring. This notion – and the iconic status of this gem – did not come about by accident.

The story goes back to 1870, when an Oxford University dropout named Cecil Rhodes set off to try his luck in the Cape Colony – modern-day South Africa, then a key British domain.

Seeing the burgeoning diamond mining sector there, he began renting water pumps to diamond prospectors to prevent flooding of the mines. Then, over the next 20 years, Rhodes and his partner Charles Rudd proceeded to buy out hundreds, and then thousands, of small mines and “claims” – landholdings believed to contain diamonds – often for a pittance when their owners faced bankruptcy. Most miners were small operators, and Rhodes and Rudd had access to serious financial capital – notably the Rothschild banking empire – through their connections in London. As the two partners combined claims into larger mining units, overhead costs were reduced, and operations became more profitable.

The partners incorporated as De Beers Consolidated Mines, De Beers being the name of one of the mines they took over. By 1888, the company had a near-monopoly of South African claims and active diamond mines. With diamonds making up more than 25 percent of South African exports in 1900, De Beers became a powerhouse of the country’s economy, controlling some 90 percent of the world’s total diamond supply. Rhodes himself became a leading imperial figure, serving as prime minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

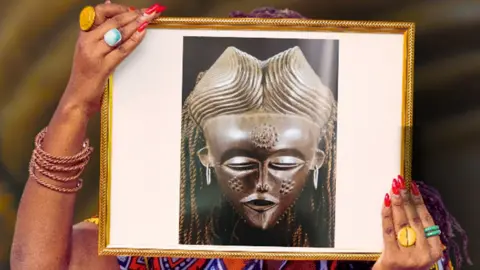

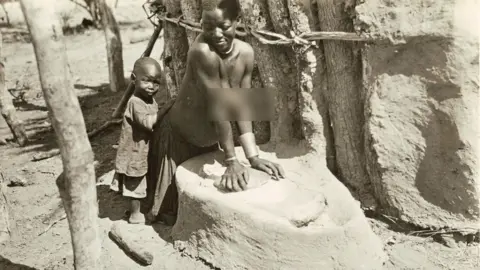

De Beers was founded upon the racist policies of South Africa, which at the time was ruled by a white minority. The diamonds were extracted by Black miners earning subsistence wages, while De Beers’s white, European-origin shareholders enjoyed the profits.

Following Rhodes’s death in 1902, control of De Beers ultimately passed to German-born entrepreneur Ernest Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer used a combination of financial incentives, strategic pressure, and diplomacy to persuade diamond suppliers in other countries to sell exclusively through the London-based and De Beers-owned “Central Selling Organization” (CSO), which in the 1930s became the unified sales channel for virtually all the world’s pre-cut diamonds. This enabled De Beers to stockpile diamonds, strictly control the release of stones to the global market, and effectively control prices – thereby creating an illusion of diamond scarcity worldwide.

Meanwhile, De Beers sought to enhance global demand for diamonds. In 1946, the company hired NW Ayer, a Philadelphia-based advertising agency, which one year later came up with the legendary slogan, “A diamond is forever”. This reframed the diamond and, specifically, the diamond engagement ring, as a symbol of “eternal love”. Through mass advertising, product placements in films, and celebrity PR – for example, lending jewellery to actors for major events – the campaign transformed the diamond market in the US, Europe and Japan.

Lasting 64 years, until 2011, this campaign was an astounding global success, with Ad Age magazine naming “A diamond is forever” as the top advertisement slogan of the 20th century. De Beers had manufactured a social norm, with the diamond engagement ring becoming almost mandatory in every developed market. While previously, a fiance might give a locket, a string of pearls, or a family heirloom to his intended, the number of American brides with a diamond ring climbed from 10 percent in 1940 to some 80 percent in 1980. In Japan, this figure rose from less than 5 percent in 1960 to 60 percent by 1981.

By the early 1950s, a diamond ring typically cost about $170 – about $2,300 in today’s money. De Beers advertisements initially suggested spending one month’s salary on an engagement ring, but by the 1980s, they were posing the question: “How can you make two months’ salary last forever?” Consumers appeared undeterred by the fact that a diamond’s resale value was typically just 50 percent of its original retail price (in contrast to gold, which has an “official” benchmark price set twice-daily).

By the time Marilyn Monroe sang “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend” in 1953 and the James Bond film “Diamonds Are Forever” was released in 1971, the diamond had become an icon.

‘Cartel behaviour’

By the late 1970s, De Beers was annually distributing some 50 million diamond carats, with sales of more than $2bn in the US alone.

But as the 1980s rolled around, problems started to emerge for the company.

De Beers came under increasing scrutiny as the anti-apartheid movement gained momentum in Europe and the United States. Reports of its working conditions were shocking: low pay for mineworkers, minimum safety training and crowded dormitory housing surrounded by barbed wire and security checkpoints. This negative publicity put De Beers firmly in the spotlight as one of the prime beneficiaries of apartheid.

De Beers had already fought off allegations of “cartel behaviour” from the US Department of Justice. But in 1994, the company was indicted by a US grand jury on price-fixing charges. The company was barred from doing business in the US, where its executives could no longer set foot for fear of arrest.

In the late 1990s, reports that the diamond trade was financing brutal civil wars in Angola, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo further soured consumer sentiment.

Rebel groups targeted “alluvial” diamond mines – relatively easy-to-extract surface deposits, often in riverbeds – selling stones into the informal “grey” market and using the profits to buy weapons. The phrase “blood diamonds” entered the lexicon as investigative articles depicted enslaved children with pickaxes and shovels. De Beers was accused of turning a blind eye, if not outright complicity. The company’s sales declined more than 20 percent in two years, from about $5.7bn in 1999 to $4.45bn in 2001, with other diamond suppliers such as Angola’s Endiama and Russia’s Alrosa equally affected.

But since the early 1990s, changes had been afoot at De Beers. Facing pressure from South Africa’s newly elected African National Congress (ANC), it had introduced better conditions and wages for its mainly Black mineworkers. At the same time, Black South Africans also began to occupy some management roles.

Meanwhile, the US indictment meant the company had no choice but to terminate its CSO in 2000, ushering in competition from other producers. Diamond prices, no longer set and dictated by the CSO, became more volatile, subject to fluctuating demand, economic cycles, and geopolitical conditions.

To counter the blood diamond backlash, De Beers helped implement the “Kimberley Process” in 2003, through which diamond dealers can trace the origin of diamonds and authenticate “clean’’ diamonds with a microscopic stamp.

Not forever?

Today, natural diamonds may have lost some of their allure with the rise of “lab-grown” stones and “diamond simulants” such as cubic zirconia, which are up to 90 percent cheaper than the mined variety and often distinguishable from the real thing only by experts using specialised equipment.

Over the past two years, the diamond industry has been hit by a “perfect storm” of cheaper synthetic stones, weak consumer demand in the US and China, sanctions against Russia and, more recently, high US tariffs. This has had a widespread adverse impact: the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC) reported that rough diamond imports dropped 35 percent in 2024, with overall trade declining by 25 percent year-on-year (from $32.5bn to $24.4bn) – and in the Indian gem processing hub of Surat, at least 50,000 diamond workers were rendered jobless in 2024. At least 80 diamond workers in India have died by suicide in the past two years.

In 2011, the Oppenheimer family sold its interest in De Beers to the London-based mining corporation Anglo American, another major shareholder, for just over $5bn. De Beers is now once more up for sale, again with a $5bn price tag, as Anglo American seeks to exit the declining diamond market in favour of copper, iron ore and rare earth minerals.

Despite the volatile market conditions, total global consumer diamond sales were valued at approximately $100bn in 2024, with the average price of $6,750 for a diamond ring in the US, according to the Natural Diamond Council – about 1.3 months’ standard wage in the United States, but about eight months’ worth of the global median income. For those of greater means, London’s Harrods reportedly has a 228.31 carat, pear-shaped diamond available to view by private appointment – with a price estimated to be in excess of $30m.

This article is part of “Ordinary items, extraordinary stories”, a series about the surprising stories behind well-known items.

Read more from the series:

How the inventor of the bouncy castle saved lives

How a popular Peruvian soft drink went ‘toe-to-toe’ with Coca-Cola

How a drowning victim became a lifesaving icon

How a father’s love and a pandemic created a household name

How Nigerians reinvented an Italian tinned tomato brand

How a children’s chocolate drink became a symbol of French colonialism