Dodgers fall to Brewers, extend losing streak to five games

MILWAUKEE — The game plan, manager Dave Roberts said Tuesday afternoon, was simple.

As the Dodgers prepared to face Milwaukee Brewers phenom Jacob Misiorowski, a hard-throwing and supremely talented right-hander making just his fifth career MLB start, the club’s manager repeated one key multiple times during his pregame address with reporters:

“Stress him as much as we can.”

Given Misiorowski’s inexperience, the idea was to work long at-bats, drive up his pitch count and “be mindful of [making] quick outs,” Roberts said.

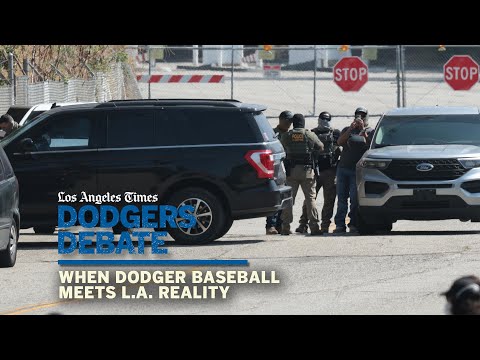

The Brewers’ Jacob Misiorowski shouts during the sixth inning of a game against the Dodgers Tuesday in Milwaukee.

(Aaron Gash / Associated Press)

“If he’s got to keep repeating pitches, there might be a way for some base hits, some walks,” he added. “Again, create stress, and hopefully get a couple big hits.”

A big hit came early, with Shohei Ohtani leading off the game with his 31st home run of the season. But after that, the only stress evident at American Family Field on Tuesday came from the Dodgers’ lineup, which struck out 12 times against Misiorowski during a 3-1 loss to the Brewers. It was the Dodgers’ fifth straight loss.

The Ks came quickly following Ohtani’s early blast (his ninth leadoff home run of the season, and one that set a new Dodgers record for total home runs before the All-Star break).

Mookie Betts fanned on a slider in the next at-bat. Freddie Freeman whiffed on a curveball after him. Andy Pages froze on a 100.8 mph fastball, one of 21 triple-digit pitches Misiorowski uncorked from his wiry 6-foot-7, 197-pound frame.

Misiorowski struck out three more batters in the second to strand a two-out Dalton Rushing single. He worked around Miguel Rojas’ leadoff double in the third with two more punchouts, getting Ohtani with a curveball this time and Freeman with the same pitch after a generous strike call got the count full.

From there, the Dodgers didn’t stress Misorowski again until the sixth, when Ohtani drew a leadoff walk and Betts slapped a single through the infield. With one out, however, Ohtani was thrown at the plate trying to score from third on Pages’ chopper up the line. Then Michael Conforto grounded out to first to retire the side, sending Misorowski skipping back to the dugout with a few thumps of his chest at the end of a six-inning, one-run start that saw all 12 strikeouts come the first five frames (tying the most strikeouts by any MLB pitcher in the first five innings of a game since 2008).

Opposite Misiorowski, Dodgers veteran Clayton Kershaw produced a solid six-inning, two-run start in a vastly different way. With his fastball still topping out at 90 mph, and the 37-year-old managing only three strikeouts in his first start since joining the 3,000 club last week, Kershaw instead navigated the Brewers with a string of soft contact.

The only problem: The Brewers still found a way to build a rally in the bottom of the fourth.

After singling on a swinging bunt up the third-base line his first time up, Milwaukee catcher William Contreras did the same thing to lead off the inning. Then Jackson Chourio beat the shift on a ground ball the other way.

That set up Andrew Vaughn for a line-drive RBI single to center, tying the score. In the next at-bat, Isaac Collins also found a hole in the infield, sneaking another ground-ball single between Betts and Rojas on the left side of the infield to give Milwaukee a 2-1 lead.

Even after Misiorowski departed, a shorthanded Dodgers lineup (which was once again without injured veterans Teoscar Hernández and Tommy Edman, as well as primary catcher Will Smith on a scheduled off day) couldn’t claw its way back.

The Brewers’ bullpen retired all nine batters it faced. Sal Frelick took Kirby Yates deep for an insurance run in the eighth. And on a day the Dodgers intended to create stress, they were instead dealing with the headache of a season-long five-game losing streak.