New fraud claims emerge in L.A. County $4-billion sex settlement

It felt like the kind of thing that must happen in Hollywood all the time: a hundred bucks to be a movie extra.

Austin Beagle, 31, and Nevada Barker, 30, said they were trying to sign up for food stamps this spring when someone offered them a background role outside a county social services office in Long Beach. They thought the gig seemed intriguing, albeit a bit unusual.

The offer came not from a casting director, but a man hawking free cellphones. The filming location was, oddly enough, a law firm in downtown Los Angeles.

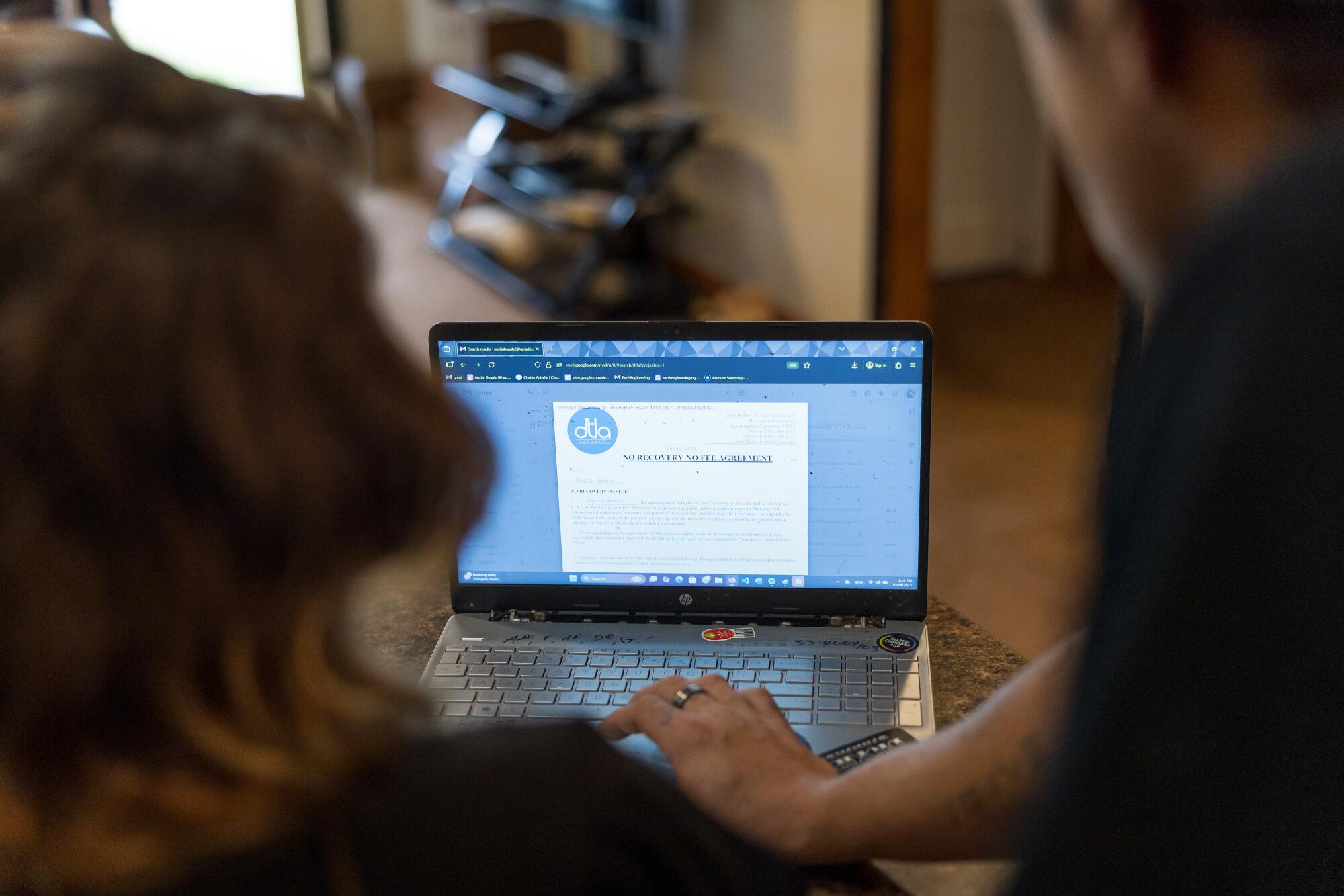

Like many DTLA clients, Austin Beagle and Nevada Barker signed a retainer agreement that entitles the firm to 45% of their payout.

(Joe Garcia / For The Times)

Maybe this was how actors were recruited here, they figured. The couple had recently moved from the remote ranching town of Stinnett in the Texas panhandle, and the recruiter seemed to appreciate their Southern drawl. They hopped on a bus, excited to make $200 between them.

“They said we’d be extras,” said Beagle, who was unemployed at the time. “But when we got to the office, that’s not what it was at all.”

The couple said they arrived at the lobby of Downtown LA Law Group. A Times investigation published earlier this month found seven plaintiffs represented by the firm who claimed they received cash from recruiters to sue the county over sex abuse, which could violate state law. Two said they had never been abused and were told to manufacture their claims.

Downtown LA Law Group has denied any involvement with the recruiters who allegedly paid plaintiffs. The firm said in a statement it would never “encourage or tolerate anyone lying about being abused” and has been conducting additional screening to remove “false or exaggerated claims” from its caseload.

Four days after The Times’ investigation was published, the firm asked for a lawsuit on behalf of Carlshawn Stovall, one of the men who said he fabricated claims, to be dismissed with prejudice, meaning the case cannot be refiled.

The firm requested a second case spurred by Juan Fajardo, who said he made up a claim using the name of a family member, to be dismissed with prejudice on Sept. 9 after Fajardo says he told lawyers he wanted to drop the lawsuit.

Now, with Beagle and Barker, two more have come forward to allege they were told to invent the stories that led to their lawsuits.

Austin Beagle and Nevada Barker said they’d been in Southern California only a few months when they were flagged down outside a social services office where they were hoping to enroll in food stamps. The couple have since moved back to Stinnett, Texas.

(Joe Garcia / For The Times)

The couple said that when they arrived at DTLA’s offices in April, a man came down to the lobby with a clipboard and gave them a piece of paper to memorize before going upstairs. They assumed this was the role they’d be playing — with room to go off script.

“They told us to say that we were sexually abused and harassed by the guards in … Las P? I can’t think of the institution’s name,” said Beagle, who added he was told to say the incidents occurred around 2005.

“The worse it was the better,” he recalled being told.

On April 29, Downtown LA Law Group filed a lawsuit against the county on behalf of 63 plaintiffs, including Beagle and Barker, who claimed they were abused at Los Padrinos, L.A. County’s juvenile hall in Downey. The couple are now part of the $4-billion settlement.

Allegations of potential fraud and pay-to-sue tactics have rocked both L.A. County government and powerhouse law firms, which are scrambling to figure out how to salvage the largest sex abuse settlement in U.S. history.

Perhaps no group has been shaken more than sex abuse victims themselves, who fear allegations of false claims could derail what they hoped would be a life-changing settlement.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” said Jimmy Vigil, 45, who sued the county in December 2022 for alleged sexual abuse by a probation officer at a detention camp in Lancaster.

Vigil said he was repeatedly molested as a 14-year-old and forced to masturbate in front of other teens while the guard watched.

“It makes me feel disgusted,” said Vigil, now a mental health case manager in Ventura County. “You have absolutely no clue what I went through. You have no clue how hard I have strived in life to make it to where I am at today.”

Jimmy Vigil, now a mental health case worker in Ventura, said he was repeatedly molested as a teenager and forced to masturbate in front of other teens.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Barker and Beagle said that after memorizing the card with the basics of their story, they were taken upstairs to a room at DTLA’s office where about 20 people were waiting. Everyone seemed confused, they said.

They “were asking us ‘Hey, did y’all promise to get paid? And we said ‘Yeah, somebody told us that we’d get paid $100 if we come in,” Beagle said. “Everybody was just concerned about getting paid whatever they were promised.”

DTLA said in a statement it has “never directed, nor do we have any knowledge that anyone was ever paid, hired, or brought to the DTLA office, or was asked to memorize a script of any kind under the guise of filmmaking,”

“We are not filmmakers,” the firm said. “No one authorized on behalf of the firm has ever promised or implied movie extra work as a means of retaining clients.”

Beagle and Barker said they were called in together to a glass cubicle where a woman spent 15-20 minutes asking them questions about their story of abuse. Barker said she struggled to come up with details because “it was all made-up stuff.”

Beagle said he thought maybe the staffers in the law firm were also acting, pretending not to know this was “a fake thing.”

“Like, they were testing us all out to see if we knew how to act — just play the part,” Beagle said. “Like, this was a trial thing.”

The couple said they were befuddled at the interaction but figured they’d done enough to get their money; the receptionist told them to come back in a few hours to collect.

The firm said, in some circumstances, it provides “interest free loans to clients once they have retained our services.”

Beagle and Barker said they frittered away two hours at Pershing Square a few blocks away until around 4 p.m. It was only when they came back to the firm, they said, that it became clear there was no movie.

A man named Kevin paid them $100 each, and told them they were part of a massive settlement involving juvenile halls they’d never heard about until that afternoon. The man told them they could get $100 for each additional person they referred to go through the same process, Beagle said.

“We walked out thinking I don’t know how legit this is and we might even get f— in trouble for it,” Beagle said.

Like most sexual abuse lawsuits, the suit was filed using only plaintiffs’ initials. The Times reviewed paperwork that DTLA provided to Beagle and Barker, which they signed in order to become clients on April 21 and to opt into the L.A. County settlement on May 29.

Under the settlement, each plaintiff could be eligible for anywhere from $100,000 to $3 million. Retainer agreements for Beagle and Barker reviewed by The Times show DTLA would get 45% of their payout.

Beagle and Barker said they aren’t banking on getting any money from L.A. County. After all, they said, they grew up in Texas, more than a thousand miles away from the abuse-plagued facilities.

“We need it, but it’s not ours. It’s like finding a wallet,” Barker said. “Return it.”

A Times investigation published earlier this month found plaintiffs represented by Downtown LA Law Group who claimed they received cash from recruiters to sue L.A. County over sex abuse. Four now say they were told to make up the claims.

(Carlin Stiehl / Los Angeles Times)

Among some survivors, there is a palpable fear that the fraud allegations will steamroll the settlement, overshadowing the fact that many county-run facilities were home to unchecked abuse and torpedoing their chance of receiving a life-changing sum.

The Times interviewed eight victims for this article represented by Slater Slater Schulman, ACTS LAW Firm, McNicholas & McNicholas, and Becker Law Group. Many said they were aghast at learning the worst years of their life may have become fodder for quick cash.

“It felt like a kick in the gut,” said Trinidad Pena, 52. “For somebody just to lie about it was just sickening.”

On Sept. 18, Pena said, she was eating a pancake breakfast at a homeless services center in Long Beach when she learned she had something in common with a woman sitting on the picnic bench next to her.

Both had filed lawsuits against L.A. County alleging sexual abuse at county-run facilities. Both of them were part of the county’s $4-billion settlement. But she was the only one, she believed, who had actually been abused.

The woman told her she’d been paid $20 to sue by a woman who hung around on the sidewalk outside the community center clutching a clipboard, she said.

The Times could not reach the recruiters allegedly responsible for paying plaintiffs for comment.

Trinidad Pena, who sued in 2022 over sex abuse, said she was jarred to find herself at breakfast with a woman who told her she’d been paid to sue the county.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Pena sued L.A. County in December 2022 over an alleged rape when she was 12 by a staff member at MacLaren Children’s Center, a shuttered youth shelter now infamous for predatory staff. No amount of cash is going to erase the scars from that, she says. But it would help.

Last month, Pena traded in her New Orleans shotgun apartment for the streets of Southern California, where she was raised. The move was, she said, a Hail Mary attempt to get medical treatment through the state’s public benefits for a cyst sprouting behind her right eye that made her vision wobble and her head crackle with pain.

She is currently living on $1,206 a month in and out of her van with a failing shunt in her head, which doctors implanted to treat her cyst. She eats mostly the nonperishable Trader Joe’s snacks she brought from Louisiana.

A six- or seven-figure settlement could help save her life, Pena said.

“I’m going to have myself a hell of a Charlie Sheen party and take a nosedive off a balcony at the Chateau Marmont if I do not get some sort of relief,” said Pena, who says she grew up in foster care near the legendary West Hollywood hotel.

Part of what has made the false claims so infuriating, victims say, is that L.A. County youth detention facilities were indeed home to horrific abuse decades ago.

Kizzie Jones, 47, said she’s on antidepressants as a result of a female probation officer who allegedly molested her twice a week and groomed her with bags of chips and bottles of conditioner.

Robert Williams, 41, says he has no friends — a near-total isolation he said traces back to repeated sexual assaults in the shower he suffered as a teen.

Mario Paz, 39, said a guard molested him under the guise of soothing his genitals with milk after he was pepper sprayed while naked. The abuse, he says, has left him traumatized to the point that he is unable to change his children’s Pampers.

All three of them filed lawsuits against the county alleging sexual abuse by county probation officers.

Mario Paz, 39, said his time at Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall left him traumatized and damaged the relationship he has with his own children.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

“For someone to capitalize on something that they never endured or never experienced, I think it’s a travesty,” said Cornelious Thompson, a 51-year-old community health worker, who sued the county in December 2022.

When he was around 13 at Los Padrinos, Thompson says he was put on psychiatric medication that knocked him out. He woke up in his unit sore with his pants hanging by his knees, bleeding. It took him years to tell anyone.

He said he recently lost his job with a contractor for the county’s health department due to budget cuts. The county had to slash spending, in part, to pay for the $4-billion settlement.

It was “bittersweet,” he says, losing his job because the county was finally paying for what he said he endured as a teenager.

Only now, a new fear has crept in as two more people say they made up claims: Will he still be believed?