With the 1980s came an influx of Western women ascending in white-collar professions — and their increase in power demanded some formidable work wear to match.

As ruthless as she is seductive, Spanish businesswoman Marioneta Negocios (voiced by Pepa Pallarés) is among them. We meet her when she lands in Quito, Ecuador, to wreak havoc in Gonzalo Cordova’s stop-motion animated show, “Women Wearing Shoulder Pads,” Adult Swim’s first-ever Spanish-language program, which premiered Sunday.

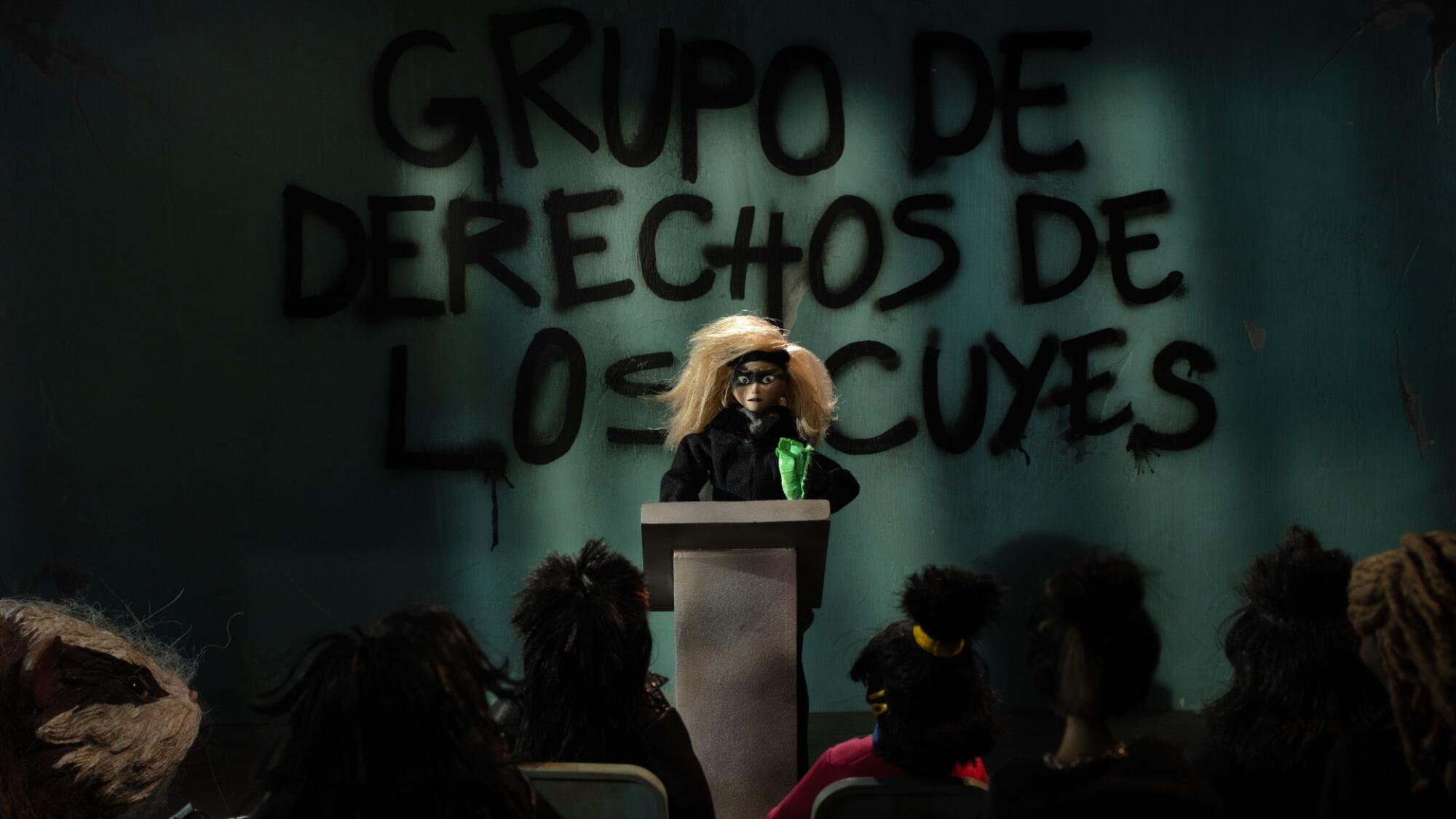

In the South American country, cuys (guinea pigs) are part of the local diet, but the conniving Marioneta wishes to change the local mindset so that the creatures are seen as pets. Her plan angers Doña Quispe (Laura Torres), who makes a living selling cuys to be eaten, leading to a melodramatic feud.

True to her name, Marioneta is a puppet whose look is immediately recognizable as that of Carmen Maura’s character Pepa in Pedro Almodóvar’s 1988 “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.” The show is profoundly indebted to Almodóvar’s universe.

Cordova, 39, lived in Ecuador and Panama until he was 6 years old, when his family moved to South Florida. He discovered American culture through copious hours of TV, with “The Simpsons” and comedian Conan O’Brien becoming key influences on his sensibilities.

“It’s just such a joy to have this TV show that mixes together all these childhood memories of Ecuador, but also TV and movies, smashing them together into one thing,” he says during a recent video interview from his home in Pasadena.

“Women Wearing Shoulder Pads” from creator Gonzalo Cordova.

(Warner Bros)

The genesis of “Women Wearing Shoulder Pads” occurred at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cordova had been working on a Mexican American project, but he ached to create a story that specifically reflected his Ecuadorean background.

Having worked as a story editor and producer on the animated series “Tuca & Bertie,” Cordova had a relationship with Adult Swim, Cartoon Network’s programming block aimed at mature audiences. He pitched them his idiosyncratic idea inspired by Almodóvar’s ‘80s films, Ecuadorean culture and his love of the Bob Baker Marionette Theater, an L.A. institution.

At first, Cordova did not tell Adult Swim that he intended for the show to be in Spanish. He tried to ease them into the idea. “I did not mention that in the pitch,” he admits. “They showed some interest and when I was writing the script, I started telling them, ‘This really should be in Spanish.’ But I always knew that was the correct way to do it.”

Executives were surprisingly receptive and allowed him to move forward with the pilot, with the caveat that they could change course. “I’m not going to lie and say that it was just smooth sailing,” Cordova explains. “But Adult Swim really listened to me and was very supportive. It has taken a big risk.”

The funniest version of this TV show had to exist in Spanish, he thought. His conviction derived from his experience writing jokes and testing them in front of an audience.

“I did stand-up comedy for eight years in New York, and if you don’t believe in the thing you’re doing and don’t fully commit, it’s not going to work,” he says. “The audience feels it. And to me, doing it in Spanish was just part of the commitment to the bit that I’m doing.”

The HBO Max show “Los Espookys,” which set the precedent that a U.S. production could premiere in Spanish, deeply emboldened Cordova in his creative impulse. “That show gave me a little bit more of chutzpah in asking for this,” he adds.

For Cordova, “Los Espookys,” created by Julio Torres, Ana Fabrega and Fred Armisen, conveyed “a Latin American sensibility and sense of humor,” which he describes as “a little offbeat and a little quirky.” That tone is also what he sought for his show.

First, Cordova wrote “Women Wearing Shoulder Pads” in English over two months with an all-Latino writers’ room, where each person had different levels of Spanish proficiency. Writing in English, their dominant tongue, allowed them to “shoot from the hip,” as he puts it. “The show really relies on absurdism, which heavily relies on instinct,” he explains.

To ensure that the jokes were not getting lost in translation, Cordova worked closely with Mexico-based Mireya Mendoza, the translator and voice director on the show. Once they had made way in the Spanish translation, the production brought on Ecuadorean consultant Pancho Viñachi to help make the dialogue and world in general feel more authentic.

“Pancho started giving us these very specific, not only slang, but also Quechua words and things that would make it feel very specifically Ecuadorean,” Cordova says. “I took that very seriously too. We spent maybe as long translating it as we did initially writing it.”

That “Women Wearing Shoulder Pads” is decidedly a queer show with no speaking male characters came from Cordova’s desire to further exaggerate the fact that in melodramas or classic “women’s pictures” the male parts are secondary to their female counterparts.

“Once you go, ‘No male characters,’ your show’s going to be queer,” he says smiling. “You wrote yourself into a corner because you can’t do a parody of these kinds of work without sex in it and without romance or passion. I was like, ‘The next step is to also make this very queer.’”

As for the decision to use stop-motion, Cordova credits Adult Swim for steering him in that direction. “Initially, when I pitched the show I wanted to do an Almodóvar film with marionettes and Adult Swim very wisely said, ‘This is going to create more complications for you,’” he recalls. “They suggested stop-motion and connected me to Cinema Fantasma.”

Based in Mexico City, Cinema Fantasma is a studio that specializes in stop-motion animation founded by Arturo and Roy Ambriz. The filmmaker brothers are also behind Mexico’s first-ever stop-motion animated feature, “I Am Frankelda.”

Cordova visited the studios throughout the production, gaining a deeper appreciation for the painstaking technique in which every element has to be physically crafted.

For Cordova, creating “Women Wearing Shoulder Pads” entailed mining his memories of Ecuador in the late ‘80s, including growing up hearing over-the-top, partially fictionalized family stories. Those recollections also helped shape the look of the puppets.

“We used a lot of film references. That’s why some of the characters just looked like they come straight out of a Pedro Almodóvar’s film,” he says. “But I also sent Cinema Fantasma a large Google Drive folder with tons of family photos. And we started finding like, ‘Doña Quispe is going to look like this relative mixed with this drawing from ‘Love and Rockets.’”

In this scene, Marioneta leads a “guinea pig rights group.”

(Warner Bros.)

The prominence of cuys in the show also stemmed from remembering how seeing them at restaurants or in cages would shock him when he returned to Ecuador as a teen after living in the U.S. for many years. Now he looks at the practice with a more mature perspective.

“I understand that this is a food and it’s no different than being served duck in a restaurant,” he says. “The show tries to make that point, but also preserves my childhood perspective on it through other characters.”

The line between the creative and the personal blurred even further because many of the costumes were based on designs that Cordova’s mother created when she was studying fashion in Panama and thought would never see the light of day.

Though she was delighted by this homage, her thoughts on the show surprised him. “My mom’s reaction has been interesting because she was like, ‘This is just a good drama.’ The comedy elements are not on the forefront for her,” Cordova says with a laugh. “For her it’s like, ‘I want to know what happens next,’ which I didn’t really expect.”

By putting Ecuador in the forefront of his mind and of this hilarious work of collage, Cordova made a singular tribute to his loved ones.

“There are so many weird little moments in the show when my family was watching and they were like, ‘Oh, that’s your tía’s name, that’s your sister’s nickname.’” Cordova recalls fondly. “It’s almost like how in superhero movies they’ll put Easter eggs, these are Easter eggs for my family only.”

But there’s another opinion Cordova is eager to hear, that of Almodóvar himself. His hope is that, if the Spanish master somehow comes across the show, he feels his admiration.

“I hope that if he does watch it, that he knows it is just very lovingly inspired by his work and that it’s not a theft,” Cordova says. “I make it very obvious who I’m taking from. I may have borrowed from him quite a bit, so I hope he sees that it’s done out of a deep respect.”