On the Shelf

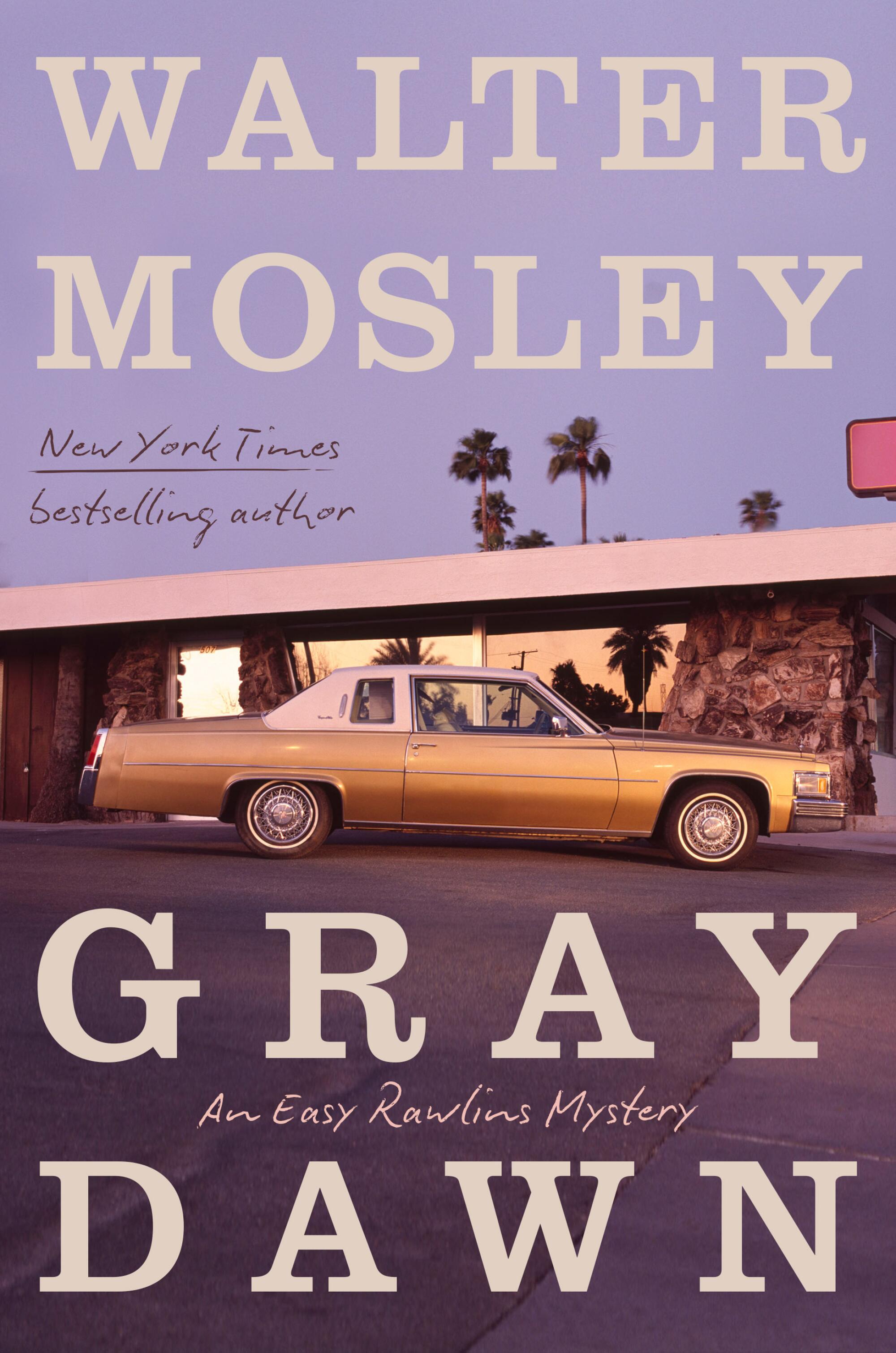

Gray Dawn

By Walter Mosley

Mulholland: 336 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Walter Mosley has penned more than 60 novels in the course of about four decades, but the Easy Rawlins mysteries are arguably his most readily recognized body of work. After writing about Easy, Raymond “Mouse” Alexander and other memorable characters in the series since their 1990 debut in “Devil in a Blue Dress,” the Los Angeles native is certainly entitled to sit back and enjoy the significant milestone in Easy’s history. But neither the success, the accolades nor the 35-year anniversary matter to Mosley as much as the work itself.

“It’s funny,” he muses over Zoom from his sun-drenched apartment in Santa Monica where he’s working one August afternoon. “Everyone has a career. Bricklayer, politician, artist, whatever. But what you think of as a career, for me it’s … I just love writing.”

It’s a good thing that he does. In the 17 mysteries in the series, Easy has given readers a front-row seat to Mosley’s vision of L.A.’s evolution from a post-World War II boom town proscribed by race and class to the tumultuous ’70s, with seismic social shifts for Black Americans, women and the nuclear family. These are the long-term changes that Easy must navigate in “Gray Dawn,” out Sept. 16.

The year is 1971 and Easy, now 50, is beset by memories of his hardscrabble Southern youth and first loves before he enlisted to serve in World War II in Europe and Africa. And while coming to L.A. after the war meant opportunity, real estate investments and success as “one of the few colored detectives in Southern California,” Easy has not lost his empathy for the underdog. So when he’s approached by the rough-hewn Santangelo Burris to find his auntie, Lutisha James, Easy leans in to help, even after he learns Lutisha is more dangerous than he suspected and brings with her an unexpected tie to his past. Then his adopted son, Jesus, and daughter-in-law run afoul of the feds and Easy must also figure out a way to save them from a certain prison sentence. Add assorted killers, business tycoons, Black militants and crooked law enforcement to the mix, all of whom underestimate Easy’s grit and outspoken determination to protect himself and his chosen family, and the recipe is set for another memorable tale.

Given Easy’s maturity and the world as it was in 1971, Mosley felt the need, for the first time, to write a note to readers to put Easy and his times into context. “When I was writing this book, I realized that, in 2025, there are some readers who may not understand where Easy’s coming from.”

Mosley’s introduction provides that frame, calling the combined tales “a twentieth century memoir” and linking them to the fight for liberation and equality. “Black people, people during the Great Enslavement,” Mosley writes, “weren’t considered wholly human, and, even after emancipation, were only promoted to the status of second-class citizenship. They were denied access to toilets, libraries, equal rights, and the totality of the American dream, which had often been deemed a nightmare.” But Easy, with his passion for community and love for the underdog, is always there to help. “He speaks for the voiceless and tried his best to come up with answers to problems that seem unanswerable.”

Despite these conditions, Mosley explains to me, the series’ recurring characters — Mouse, Jackson Blue, Fearless Jones, among others — who serve as Easy’s family of choice have prospered since the beginning of the series, Easy most of all. “Easy is a successful licensed PI, living on top of a mountain with his adopted daughter, plus his son and his family are around too. So for readers who pick up the series at this point, everything seems great. But then, Easy walks into a place [in the novel] and he’s confronted by some white guy who says, ‘Well, do you belong here?’ Before, when I had written something like that, I assumed that people are going to understand how those kinds of verbal challenges are fueled by the racism of the time. But this time I thought there are readers who may not understand it, even though it’s speaking to something about their lives or their world, even today.”

Easy Rawlins also speaks to other writers, who read the mysteries as a beacon of hope, a crack in the wall through which other voices can be heard.

S.A. Cosby, bestselling author of “Blacktop Wasteland” and “All the Sinners Bleed” and an L.A. Times Book Prize winner, clearly remembers his introduction to Easy’s world. “Reading ‘Devil in a Blue Dress’ was like being shown a path in the darkness. It spoke to me as a writer, as a Southerner and as a Black person,” he said in an email. “In some ways, it gave me ‘permission’ to write about the people I love.”

Easy also offers a unique lens through which to view L.A. Steph Cha, Times Book Prize winner for “Your House Will Pay,” discovered “Devil in a Blue Dress” as a freshman in college. “I was totally thunderstruck,” she said in an email. “This was before I had the context and vocabulary to articulate its importance in the broader literary landscape, but I knew I loved Easy Rawlins and his eye on Los Angeles. Walter was one of my primary influences when I started writing fiction. I even named a character Daphne in my second book after the missing woman in ‘Devil.’”

“‘Toes in the soil beneath my feet.’ That’s what a detective has to have. She has to know the city, its peoples, dialects, and languages. Its neighborhoods and histories. Everything you could see and touch. A detective’s mind has to be right there in front of her. Your city was your whole world.”

But why does the series endure? Cha credits the quality of the man himself: “Easy’s been through so much over 35 years, but he’s still the same guy, a man who will go anywhere, talk to anybody and bear anything, while still giving the feeling he bleeds as much as the rest of us.”

But Easy’s also thinking about the future, which in “Gray Dawn” means helping Niska, a young Black woman in his office, develop into a detective. Along the way, he shares his creed and his hope for what she will become one day: “‘Toes in the soil beneath my feet.’ That’s what a detective has to have. She has to know the city, its peoples, dialects, and languages. Its neighborhoods and histories. Everything you could see and touch. A detective’s mind has to be right there in front of her. Your city was your whole world.”

Back on our Zoom call, I ask Mosley whether he was thinking of Raymond Chandler’s seminal 1944 essay “The Simple Art of Murder” and the oft-quoted line “Down these mean streets…” when writing that passage. Not consciously, but he liked the comparison because “Easy in many ways is the opposite of Philip Marlowe.”

Not the least of which is his willingness to help a woman become a detective. “Even though Easy is skeptical about a woman being a detective,” he explains, “he recognizes it’s the 1970s and, with the women’s movement, he’s willing to help her if that’s what she wants.”

As the song goes, the times they are a-changin’, and Easy with them. What does Mosley hope readers take away from “Gray Dawn,” Easy’s midlife novel? “I want them to see how Easy has developed and changed over the years. And that family, even though Easy’s doesn’t look like the nuclear family, is what America has always been about.”

“I love being a writer so much that even if I had much less success, or even none, I would still be doing it,” Walter Mosley says.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Mosley’s also experienced enough to know that what writers hope readers understand and what readers actually see in their writing can be very different. And while he appreciates comments from writers like Cosby and Cha, he puts it all in perspective. “As a writer, I think it’s important for you to remember not to judge your success by what other writers have said about your work. Because writers more than anybody in literature are confused about what literature actually is. Writers will say, ‘I did this, and I did that, and I wrote this, and this was my intention, and I started here, and I moved it there.’ But the truth is you’ve written a book, you’ve created the best thing you could have written, and all these people have read it. And for every person who has read it, it’s a different book.”

Mosley is also a talented screenwriter, having served as an executive producer and writer on the FX drama “Snowfall.” Most recently, he shared a writing credit (with director Nadia Latif) for the screenplay of the upcoming film “The Man in My Basement” — an adaptation of his 2004 standalone novel — starring Willem Dafoe and Corey Hawkins. Mosley is particularly cognizant of how book-to-film translations can have different meanings for their creators.

“With very few exceptions, books and the films that they spawn are very different,” he explains. “And they have to be because books come to life in the mind of readers, who imagine the characters and places the writer describes. And books are language, and your understanding through language as a reader is a part of the process. But a film is all projected images. So when somebody says they’re writing a book, you tell them, ‘Show. Don’t tell.’ When you produce or direct a movie, they just say, ‘Show.’”

Mosley praises Latif, who, in her directorial debut, leaned into certain aspects of his novel. “She’s very interested in the genre of horror and uses certain elements of it in the film,” he notes. “But I don’t think she could do that without those elements already being there in the novel.”

Beyond “Gray Dawn” and the forthcoming film, Mosley’s collaborating with playwright, singer and actor Eisa Davis on a musical stage adaptation of “Devil,” as well as working on a monograph about why reading is essential to living a full life. But regardless of the medium, Mosley’s purpose is crystal clear. “For me, it’s about the writing itself,” he says, leaning in to make his point. “I love being a writer so much that even if I had much less success, or even none, I would still be doing it.”