Before the start of the season, Dodgers first base and infield coach Chris Woodward pulled Mookie Betts aside one day, and had him envision the ultimate end result.

“You’re gonna be standing at shortstop when we win the World Series,” Woodward told Betts, the former Gold Glove right fielder in the midst of an almost unprecedented mid-career position switch. “That’s what the goal is.”

Two months into the season, the Dodgers believe he’s checking the requisite boxes on the path toward getting there.

“I would say, right now he’s playing above-average shortstop, Major League shortstop,” manager Dave Roberts said this week. “Which is amazing, considering he just took this position up.”

Betts has not only returned to shortstop this season after his unconvincing three-month stint at the position last year; but he has progressed so much that, unlike when he was moved back to right field for the stretch run of last fall’s championship march, the Dodgers have no plans for a similar late-season switch this time around.

“I don’t see us making a change [like] we did last year. I don’t see that happening,” Roberts said. “He’s a major league shortstop, on a championship club.”

“And,” the manager also added, “he’s only getting better.”

It means that now, Betts’ challenge has gone from proving he belongs at shortstop to proving he can master it by the end of the season. The goal Woodward laid out at the beginning of the year has suddenly become much more realistic now. And over the next four months, Betts’ ability to polish his shortstop play looms as one of the Dodgers’ biggest X-factors.

“Getting to that, even when he’s as good as he is now, there’s still a lot to learn,” Woodward said. “He’s done good up to this point. So how do we maintain that [progress]?”

In Year 1 of playing shortstop on a full-time basis last season, Betts’ initial experience was marked by trial and (mostly) error. He struggled to make accurate throws across the diamond. He lacked the instincts and confidence to cleanly field even many routine grounders. In his three-month cameo in the role — one cut short by a midseason broken hand — he committed nine errors and ranked below-league-average in several advanced metrics.

“Last year,” first baseman Freddie Freeman said when reflecting on Betts’ initial foray to the shortstop position, “it was like a crash course.”

In Year 2, on the other hand, Betts has graduated to something of a finishing school.

Unlike last year, when the former MVP slugger switched positions just weeks before opening day, Betts had the entire offseason to prepare his game. Over the winter, he improved the technique of his glovework while fielding balls. He trained on how to throw from lower arm slots than he had in the outfield. He focused on keeping a wider and more athletic base in order to adapt to funny hops and unexpected spins. He established a base of fundamentals that, last year, he simply didn’t have; providing renewed confidence and consistency he’s been able to lean on all season.

“Preparation,” Betts said recently about the biggest difference in his shortstop play this year. “[I have been able] to prepare, have an idea of what I’m doing, instead of just hoping that athleticism wins. At this level, it doesn’t work like that. So you have to have an idea of what you’re doing. And I work hard every day. I’m out there every day early. Doing what I can to be successful.”

Such strides have been illustrated in Betts’ defensive numbers. He currently ranks seventh among qualified MLB shortstops in fielding percentage, his three errors to this point tied for the fewest among those who have made at least 50 starts. His advanced metrics are equally encouraging, ranking top-five in outs above average and defensive runs saved.

“He looks like a major league shortstop right now,” Roberts said, “where last year there were many times I didn’t feel that way.”

A finished product, however, Betts is still not.

There are subtle intricacies he has yet to fully grasp, such as where to position on relay throws from the outfield. There are infrequent, higher-difficulty plays he’s yet to learn how to handle.

One important teaching moment came early in the season, when Betts’ inability to corral a hard hooking one-hopper in a game against the Washington Nationals led to him and the coaching staff adding more unpredictable fungo-bat fielding drills into his daily pregame routine.

“It just kind of prompted a conversation of, ‘You’re gonna get different types of balls, and those are pretty rare. But what’s the process of catching that ball? And what do we need to practice?’” Woodward recalled, leading to changes that were enacted the next day.

“The drills we do now, I don’t know if anybody else can make them look as easy as he now does,” Woodward added. “When he first started, you could tell, ‘Oh man, it’s uncomfortable.’ But now, I smoke balls at him … and he’s just so under control.”

Another moment of frustration came last Sunday in New York, when Betts athletically snared a bouncing ball on his forehand up the middle … but then airmailed a backhanded, off-balance flip throw to second base while trying to turn a potential double play.

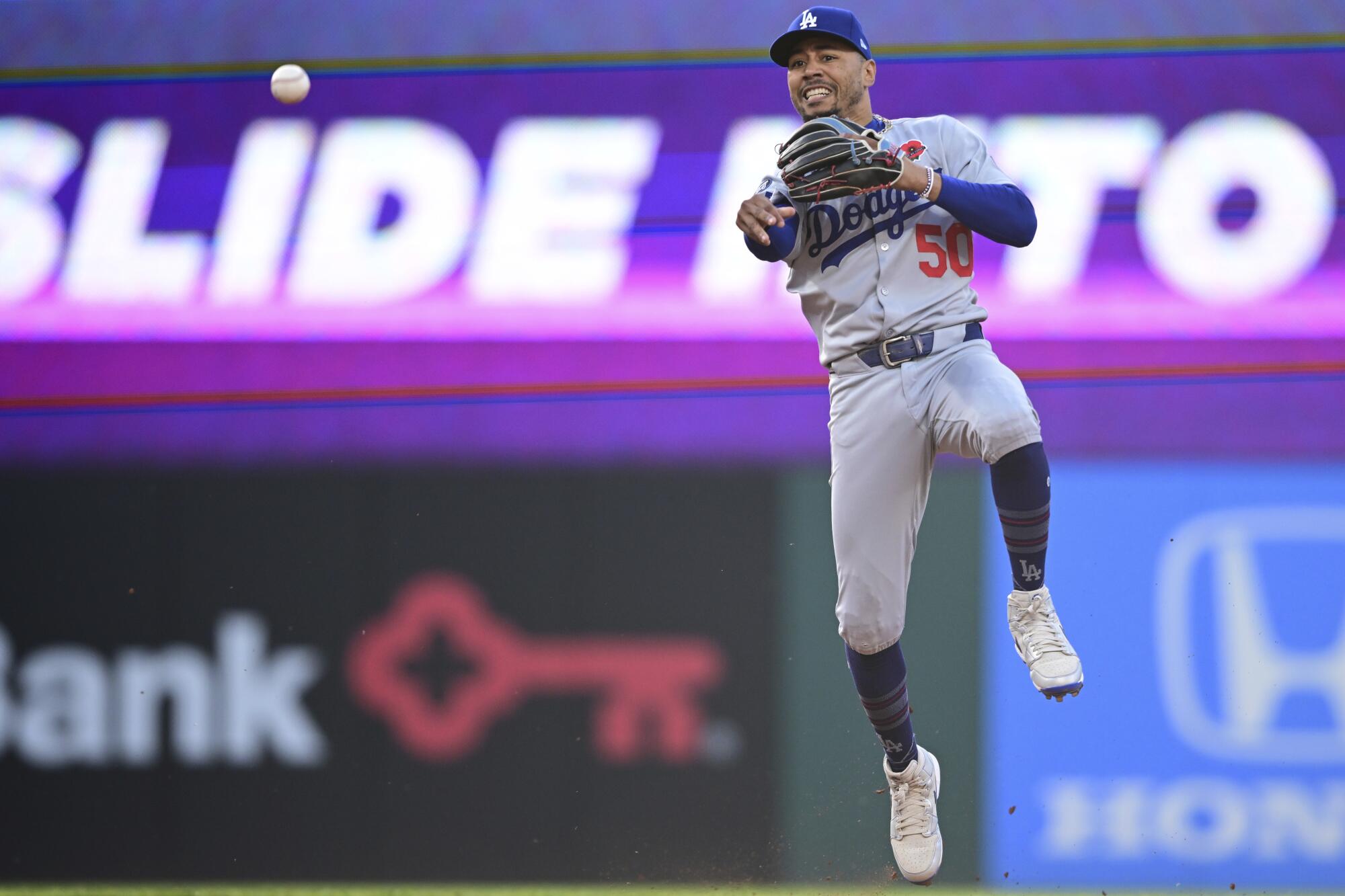

Dodgers shortstop Mookie Betts throws to first base during Monday’s game against the Cleveland Guardians.

(David Dermer / Associated Press)

“That was the first time ever in my life I’ve had to do that,” Betts said days later, prompting him to seek out more advice from Woodward and veteran shortstop teammate Miguel Rojas. “Miggy was telling me I can’t stress about it, because he got to mess that play up in high-A [when he was first learning the position]. Woody told me he got to mess that play up in double-A. I’m messing this play up for the first time ever in my life — in the big leagues.”

For Betts, it can be a frustrating dynamic, having to endorse inevitable such struggles as he seeks his desired defensive progress.

“I definitely feel I’ve grown a lot, just from the routine perspective,” he said. “But I don’t want to hurt the team, man.”

Which is why, in the days immediately afterward, he then incorporated underhand flip drills into his pregame work as well.

“You’re going to have to go through those moments to learn, to understand,” said Rojas, who has been a sounding board for Betts since last year’s initial position switch. “I don’t consider that an error. I consider it a mistake that you’re gonna learn from. Because that play is gonna happen again.”

“It’s like life in general. It’s about learning from your mistakes,” Freeman echoed. “And not that that [flip play] was a mistake. But it’s like, ‘Now I know how to adjust off of that.’ If he was not even trying to attempt things, then you’ll never know what you can really achieve out there. I think he’s learning his limits of what he can do. And I think that’s the key to it.”

Such moments, of course, also underscore the inherent risk of entrusting Betts (who still has only 132 career MLB games at shortstop) with perhaps the sport’s most challenging position.

It’s one thing for such a blunder to happen in a forgettable late May contest. It’d be far less forgiving if they were to continue popping up in important games down the stretch.

There’s also a question about whether Betts’ focus on shortstop has started to have an impact on his bat, with the 32-year-old hitting just .254 on the season while suffering incremental dips in his underlying contact metrics.

The root of those struggles, Betts believes, stems more from bad habits he developed while recovering from a stomach virus at the start of the season that saw him lose almost 20 pounds. Then again, even though he has been able to better moderate his daily pregame workload compared with the hours he’d spend every day fielding grounders last season, he is still “learning a whole new position at the big-league level,” Freeman noted, “and all his focus has been on that.”

It all creates a relatively tight needle for Betts and the Dodgers to thread the rest of the year. Betts not only has to make continued strides on defense (and prove, at a bare minimum, he won’t be a downgrade from the team’s other in-house options, such as Rojas or Tommy Edman), but, he also needs to get his swing back in a place to be an impact presence at the top of the lineup.

“It’s a lot to take on, to be a shortstop in the big leagues,” Freeman said. “But once he gets everything under control, I think that’s when the hitting will pick right back up.”

It figures to be an ongoing process, one that could have season-defining implications for the Dodgers’ World Series title defense.

Still, in the span of two months, Betts has shown enough with his glove for the Dodgers not to move him — making what started as a seemingly dubious experiment into a potentially permanent solution.

“People around baseball should be paying a little more attention to the way he’s been playing short,” Rojas said.

“He’s had a lot of different plays that he’s been able to kind of see in games,” added Roberts. “He’s a guy that loves a challenge, and he’s really realized that challenge and keeps getting better each night.”