“Grounded,” the newly opened exhibition of relatively recent acquisitions of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, starts out setting a very high bar. It’s a compelling launch, even if the spotty show that unfolds in the next several rooms falls apart.

Grounded, it isn’t.

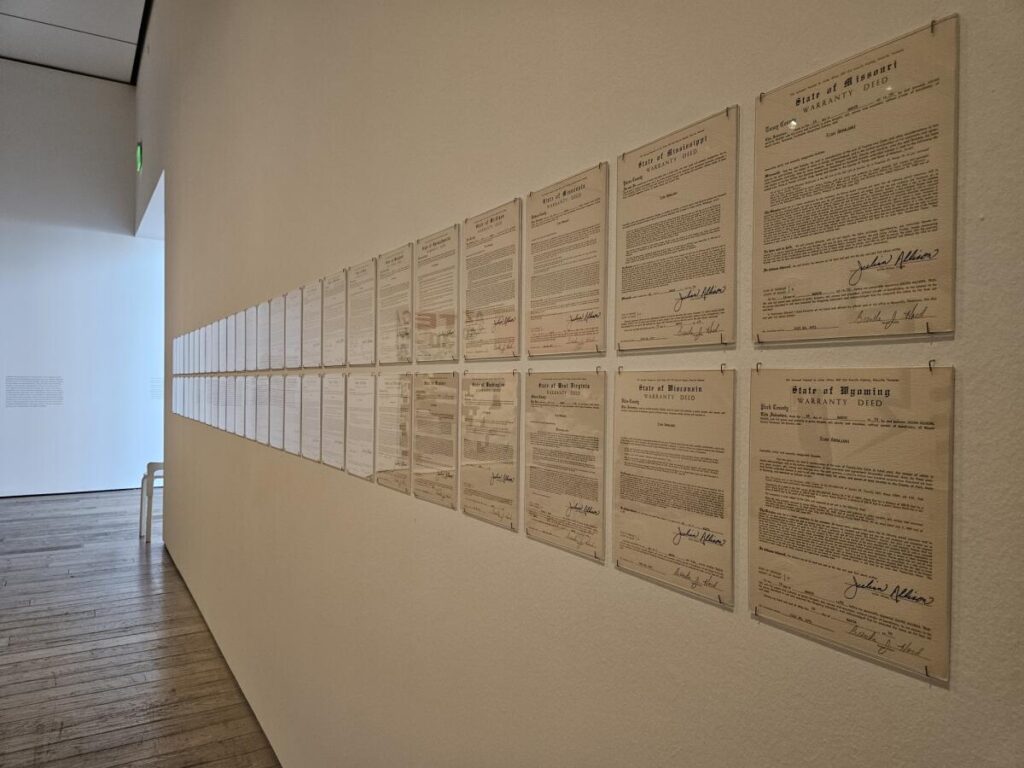

“Land Deeds,” a 1970 work by Iranian American artist Siah Armajani (1939-2020), is the opener, and it’s terrific. The piece is composed of 50 documents recording real estate purchases that the artist made in all 50 U.S. states, spending less than $100 on each. Sometimes, I’d guess, much less: Armajani only bought a single square-inch of land in each place, so the properties were cheap. Maybe that would cost a hundred bucks in Beverly Hills or Honolulu, but a square-inch of Abilene, Kan., or Whitefish, Mont., would be lucky to get a buck.

In true Conceptual art form, the notarized documents confirming the transactions are lined up on the wall in alphabetical order, from Alabama and Alaska to Wisconsin and Wyoming, in two rows of 25. Visually dry, they nonetheless quickly pull you in. These are warranty deeds, a legal document used to guarantee that a property being sold is unencumbered and the transfer of ownership from seller to buyer is legit. In good Dada and Pop art-style, the work’s title turns out to be a pun: A deed is not just a real estate certificate but an endeavor that one has undertaken.

Siah Armajani’s 1970 “Land Deeds” records his purchase of one square-inch of all 50 U.S. states.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Other artistic resonances unfold. Land art was then at the cutting edge of avant-garde activity.

By 1970, sculptors Christo and Jeanne-Claude had just wrapped a million square-feet of coastal Australia in tarpaulin lashed with rope. Robert Smithson had bulldozed dirt and rocks to build a spiral jetty coiling out into Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Michael Heizer had dug a huge trench across Mormon Mesa near Overton, Nev., making a sculptural object out of empty space. Armajani’s unusual earthwork joined in: Embracing a legal, bureaucratic form, he pointed to land as a decidedly social structure.

The document display is droll but serious. It may be a layered example of up-to-the-minute Conceptual art, deeply absorbing and surprisingly suggestive, but the deeds are also lithographs, a perfectly traditional medium. They’re signed by administrative officials — one Julian Allison, warranty trustee, and notary public Brenda J. Hord — rather than being autographed by the artist. An art experience is a social transaction.

Armajani, an immigrant working as an artist in New York but not yet a U.S. citizen, was profoundly committed to democratic principles. (His citizenship would come in the wake of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, which installed a disastrous theocracy from which the Middle East still suffers.) With “Land Deeds,” he put his finger on a critical real estate context: From the get-go, full participation in American democracy had been limited to white male landowners. The explanation was that they had a vested interest in the community.

The deeper reasons, however, were profoundly anti-democratic — the noxious intransigence of patriarchy and white supremacy in Western culture, which drastically narrowed the eligible land-owning class. Women and people of color, except in limited instances, need not apply. (And suffice to say that warranty deeds for land transfers from Indigenous people were in rather short supply.) Gallingly, this autocratic check on egalitarian participation was also spiked with an element of informed equanimity: An educated populace is essential to democracy’s successful functioning, but in the 1770s, that mostly meant white male landed gentry, since they were likely to have had formal schooling.

At LACMA, Armajani’s marvelously revealing “Land Deeds” sets the stage for “Grounded.” The show was organized by LACMA curators Rita Gonzalez and Dhyandra Lawson, and deputy director Nancy Thomas. Entry wall text — there is no catalog — says it “explores how human experience is embedded in the land, presenting the work of artists who endow it with meaning.”

But, collectively, the 39 assembled contemporary paintings, sculptures, photographs, textiles and videos by 35 artists based in the Americas and areas of the Pacific underperform. Sometimes that’s because the individual work is bland, while elsewhere its pertinence to the shambling theme is stretched to the breaking point.

Familiar photographs of figures in the landscape by Ana Mendieta, left, and Laura Aguilar, center, offer background for the theme explored in “Grounded.”

(Museum Associates / LACMA)

The land theme is so loose and shaggy that, without the contemporary time frame, the show could start with prehistoric cave paintings, toss in a Chinese Song Dynasty scroll whose pictures follow a journey down the Yangzi River, add a Central African Kongo spirit sculpture filled with grave dirt and, for good measure, suitably hang a Jackson Pollock drip painting solely because it was made by spreading raw canvas flat on the ground.

Superficial bedlam, in other words.

Some work does stand out. Across from the Armajani is Patrick Martinez’s “Fallen Empire,” which takes a sly commercial real estate approach. The poignant mixed-media painting doubles as a large shop façade of crumbling, graffitied ceramic tiles with signage attached on a tarp. The name “Azteca” evokes a long-gone historical realm, here attached to a shop now falling into ruin. Martinez scatters ceramic roses across the painting, a mordant honorific to past glory and current hopes.

In the next room, Connie Samaras’ serendipitous landscape photograph unshackles whatever might be meant by being grounded. Shot from her L.A. home in the hills, what at first appears to be a strange cloud in the night sky over the twinkling city below turns out to be the vapor trail of a Minuteman missile deployed one night in 1998. A tangle of light above a black silhouette of a palm tree emits a sulfurous glow, its nauseous beauty balanced on the tip of potential annihilation.

Also among the more engaging works are two well-known photographic excursions into the landscape. Laura Aguilar’s “Grounded #111,” from a large series that likely gave the show its name, poses her corpulent nude body before a majestic boulder in the Joshua Tree desert, as if a secular saint enclosed within a sacred mandorla.

Six adjacent photographs in Ana Mendieta’s “Volcano Series no. 2” record a performance type of Land art in which a female form seems to erupt from within the Earth, spewing a volatile shower of flaming embers and smoke. Forget placid if repressive fantasies of Adam’s rib. The volcanic explosion provides a theatrically dramatic precedent for Aguilar’s contemplative composition.

Other impressive works include Mexico City-based Abraham Cruzvillegas’ exceptional sculpture, “Autoconcancion V” — the title’s made-up word translates to “auto with song” — which upends conventional L.A. car culture. An old automobile’s beat-up rear bench seat becomes the launching pad for a wooden box holding a small fan palm, held aloft on buoyant metal rods and exuding a witty mix of aplomb and high spirits.

A 70-foot video projection by Lisa Reihana reimagines a famous scenic French wallpaper.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

New Zealand artist Lisa Reihana, who is of Māori British ancestry, transformed a famous early 19th century French scenic wallpaper designed by Jean-Gabriel Charvet into an equally extravagant, 70-foot-wide projection of video animation. The showily exoticized wallpaper, sold throughout Europe and in North America by celebrated manufacturer Joseph Dufour, was the culmination of Western public fascination with British Royal Navy Capt. James Cook’s three voyages to the Pacific. In a big, darkened room, Reihana redecorates.

Amid dreamy island landscapes, “in Pursuit of Venus [infected]” beautifully mixes interactive scenes of playful harmony and brute conflict between red-uniformed colonizers and colonized Polynesians. She maintains a nuanced sense of humanity’s transgressions and innocence, without demonizing or idealizing either side. Emblematic is a wickedly funny episode where a British plein-air painter at his easel bats away pesky tropical insects, invisible to a viewer’s naked eye, as he attempts to render a still life of a dead fish.

What either the Reihana video or the Cruzvillegas sculpture has to do with how human experience is embedded in the land — “grounded” — I cannot say, except in the most superficial ways. The land is certainly not a major focus of either one. The Cruzvillegas sculpture celebrates varieties of youthful play, while the Reihana animation ruminates on dimensions of cultural collision. The exhibition’s purported theme unhappily narrows perspectives on the assembled works of art, rather than opening wide their myriad readings.

Lisa Reihana, “in Pursuit of Venus [infected],” 2015, projected video animation.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Essentially, “Grounded” is an old-fashioned “Recent Acquisitions” show, with most works entering LACMA’s collection in the last half-dozen years or so. (The big exception is Mendieta’s “Volcano” series, easily the show’s most famous work, purchased a quarter-century ago; it’s apparently included here as a benchmark.) Six pieces are shared with the UCLA Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art as part of the new MAC3 (Mohn Art Collective) program, and the Aguilar is shared with the Vincent Price Art Museum at East L.A. College.

The exhibition is on view in LACMA’s Broad Contemporary Art Museum for eight months, until late June 2026. The unusually lengthy run will put recent art on par with LACMA’s historical departments, when the new Geffen Galleries building opens in April. Those rooms are also expected to thematize the museum’s diverse permanent collection of art’s global history.

But “Grounded” would have been better left without its imposed topic, which inadvertently casts much work as ugly stepsisters unsuccessfully trying to jam their feet into Cinderella’s glass slipper. Skepticism over the coming Geffen theme idea mounts.