On Oct. 29, 2022, the universe told Dr. Casey Means her fate lay in Los Angeles.

President Trump’s new pick for surgeon general wrote in her popular online newsletter of her epiphany, which came during a dawn hike among the cadmium-colored California oaks and flames of wild mustard flower painting the Topanga Canyon: “You must move to LA. This is where your partner is!’”

Los Angeles has been a Shangri-La for health-seekers since its Gold Rush days as the sanitarium capital of the United States.

Today, it’s the epicenter of America’s $480-billion wellness industry, where gym-fluencers, plant-medicine gurus and celebrity physicians trade health secrets and discount codes across their blue-check Instagram pages and chart-topping podcasts.

But by earning Trump’s nod, Means, 37, has ascended to a new level of power, bringing her singular focus on metabolic dysfunction as the root of ill health and her unorthodox beliefs about psilocybin therapy and the perils of vaccines to the White House.

The surgeon general is the country’s first physician, and the foremost authority on American medicine. Means’ central philosophy — that illness “is a result of the choices you make” — puts her in lockstep with Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and in opposition to generations of U.S. public health officials.

Means declined to comment. But interviews with friends and her public writings track a metamorphosis since her move to L.A., from a med-tech entrepreneur and emerging wellness guru to the new face of Trump’s “Make America Healthy Again” movement, or MAHA for short.

If confirmed, America’s next top doctor will bring another unconventional addition to the surgeon general’s uniform: a baby bump. Friends told The Times Means and her husband, Brian Nickerson, are expecting a baby this fall.

“[The pregnancy] will definitely empower her,” said Dr. Darshan Shah, a popular longevity expert and longtime friend of Means. “It might create even more of a sense of urgency.”

On this, both supporters and critics agree. Fertility is a primal obsession of the MAHA movement, and a unifying policy priority among otherwise heterodox MAGA figureheads from Elon Musk to JD Vance. In this worldview, motherhood itself is a credential.

“She’s going to say, ‘I’m a mom, and the reason why you can trust me is I’m a mom,’” said Jessica Malaty Rivera, an infectious disease epidemiologist and an outspoken critic of Means.

Mothers have long been the standard-bearers for Kennedy’s wellness crusade. “MAHA moms” flanked him at the White House during a roundtable in March, where they filmed themselves struggling to pronounce common food additives. Many flocked to Trump after the president vowed to put Kennedy in charge of the nation’s healthcare.

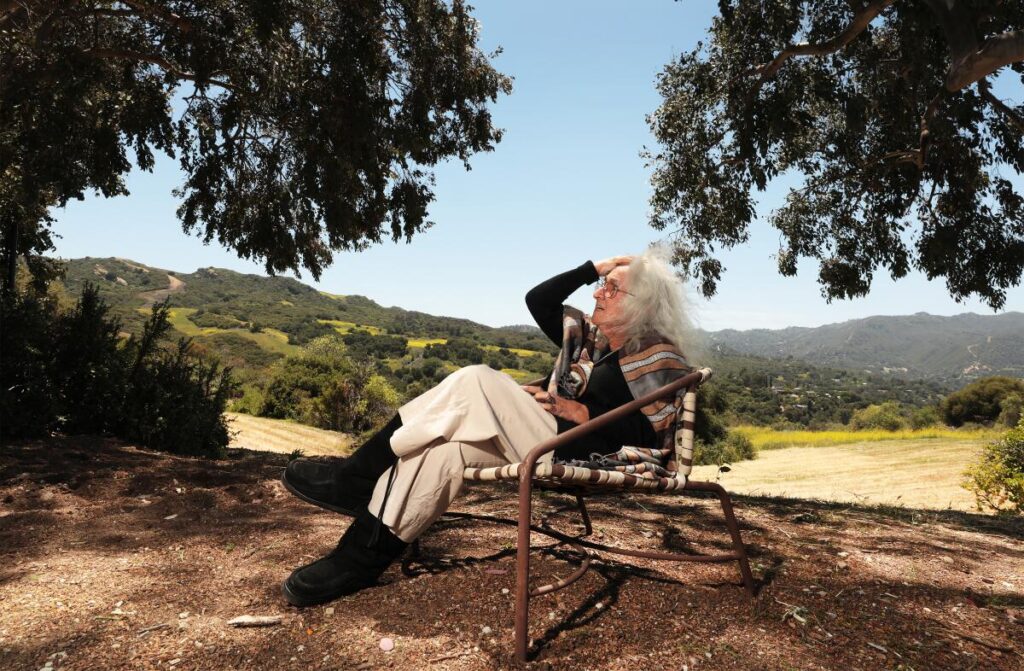

Deena Metzger at her Topanga home. Metzger is a poet, novelist, essayist, storyteller, teacher, healer and medicine woman who has taught and counseled for over fifty years.

(Al Seib/For The Times)

“It’s such a radical change that’s required [in medicine],” said the writer and healer Deena Metzger, 88, whom Means has called one of her “spiritual guides.” “It’s wildly exciting that she might be surgeon general, because she’s really thinking about health.”

Her outsider status gives her a clear-eyed perspective, her supporters say.

“The answer to our metabolic dysfunction is through lifestyle,” said Dr. Sara Szal Gottfried, an OBGYN and longtime friend of Means. “Seventy percent of our healthcare costs are due to lifestyle choices, and that’s where she starts.”

Means’ 2024 bestseller “Good Energy” touts much the same message: Simple individual changes could make most people healthy, but the medical system profits by keeping them sick.

“Moms (and families) will not stand anymore for a country that profits massively off kids getting chronically sick,” Means posted on X on Jan. 30. “Nothing can stop the frustration that is leading to this movement.”

Critics say that elides a more complex reality.

“This is what we call terrain theory — it’s the inverse of germ theory,” said Rivera, the epidemiologist. “Terrain theory has a very deeply racist and kind of eugenic origin, in which certain people got sick and certain people didn’t.”

She and others point out that Means is being elevated at the same time the administration guts public health infrastructure, slashing staff and research funding and aiming to cut billions more from public safety net programs.

“MAHA is why we are defunding the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health],” Rivera said. “Thirteen million people could be uninsured because of [Medicaid cuts].”

But trust in those institutions — and in physicians generally — has tanked in the past five years, surveys show.

The blurring of personal pathos and professional authority at a moment of crisis for institutional medicine is central to MAHA’s influence and power, public health experts say. They point to the movement’s broad appeal from cerulean Santa Monica to crimson Gaines County, Texas, as evidence that health skepticism transcends political lines.

“[MAHA] has sucked in a lot of my blue friends and turned them purple,” Rivera said. “I have people doing the mental gymnastics of ‘I’m not MAGA, I’m just MAHA.’ I’m like, ‘I don’t think you realize those two things are one thing now.’”

Means’ own celebrity is similarly vast, uniting Americans fed up with what they see as a sclerotic and corrupt medical system.

Her opposition to California’s stringent childhood vaccine mandates, enthusiasm for magic mushrooms, and obsession with all things “clean” and “natural” have endeared her to everyone from raw milk fans to anti-vaxxers to boosters of Luigi Mangione, the accused killer of a healthcare chief executive who regularly receives fan mail while awaiting trial in Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center.

“We’ve never had anyone in that role [of surgeon general] who almost anyone knew who they were,” Dr. Joel Warsh, a Studio City pediatrician and fellow MAHA luminary, whose book on vaccines “Between a Shot and a Hard Place” came out this week. “We know the public loves her.”

That adoration may yet outshine concerns over Means’ medical qualifications — despite her elite education, she left just months before the end of her residency as an ear, nose and throat surgeon at Oregon Health & Science University. Her Oregon medical license is current but inactive and her experience in public health policy is limited.

And while the nominee vigorously defends the brand partnerships that often bookend her newsletters and social media posts, others see the dark side of L.A. influence in the practice.

“L.A. is its own universe when it comes to wellness,” Rivera said. “You can convince anybody to buy a $19 strawberry at Erewhon and say it’s worth it, the same way you can sell people colonics and detox cleanses and all kinds of wellness smoke and mirrors.”

Means made her name as CEO of a subscription health tracking service whose distinguishing feature is blood sugar monitoring for non-diabetics — a practice she touts across several chapters of her book. Her newsletter readers are regularly offered 20% off $1.50-per-pill probiotics or individually packaged matcha mix promising “radiant skin” for its drinkers.

More recently, she’s partnered with WeNatal, a bespoke prenatal vitamin company whose flagship product contains almost the same essential molecules as the brands offered through Medicaid — the insurance half of pregnant Californians use. Taking it daily from conception to birth would cost close to $600.

“So many of the companies that she supports, so many of the companies selling snake oil have some connection to or presence in Los Angeles,” Rivera went on. “It is the mecca for that kind of stuff.”

Even some in the doctor’s inner circle have misgivings about the world of influence that launched her, and the administration she’s poised to join.

Deena Metzger is at the center of a web of influence surgeon general nominee Dr. Casey Means found when she moved to L.A.

(Al Seib / For The Times)

“I’m not sure the obsession with wellness is really about wellness,” Metzger said, her husky Gentle Boy lying at her feet in her home in Topanga. “There’s wellness, which is maybe even a social fabrication, and there’s health.”

The writer and breast cancer survivor has spent decades convening doctors and other healers on this mountaintop as part of her ReVisioning Medicine councils, probing the question posed variously by Soviet writer Mikhail Bulgakov and American humanitarian Dr. Paul Farmer, Jewish philosopher-physician Moses ben Maimon and fictional heartthrob Dr. Robby on “The Pitt”: Can we create a medicine that does no harm?

“How do you believe in that? Or associate with it?” she wondered about the MAHA movement her friend had helped to birth. “But If she’s there and she has power to do things, it will be good for us.”

While mainstream medical authorities and wellness gurus agree that pesticides, plastics and ultraprocessed foods harm public health, they diverge on how much weight to give MAHA’s preferred targets and how to enact policy prescriptions that actually affect them.

“We have people forming a social movement around beef tallow — let’s get that focused on alcohol reduction, tobacco reduction,” said Dr. Jon-Patrick Allem, an expert in social media and health communication. “I don’t disagree with reducing ultraprocessed foods. I don’t disagree with removing dyes from foods. But are these the main drivers of chronic disease?”